(Press-News.org) Attention editors: Under embargo by the journal Current Biology until Friday, February 24 at 11 a.m. eastern

Scientists who study the origins and evolution of the plague have examined hundreds of ancient human teeth from Denmark, seeking to address longstanding questions about its arrival, persistence and spread within Scandinavia.

In the first longitudinal study of its kind, focusing on a single region for 800 years (between 1000-1800AD), researchers reconstructed Yersinia pestis genomes, the bacterium responsible for the plague, and showed that it was reintroduced into the Danish population from other parts of Europe again and again, perhaps via human movement, with devastating effects.

The historical samples were taken from nearly 300 individuals located at 13 different archaeological sites throughout the country.

“We know that plague outbreaks across Europe continued in waves for approximately 500 years, but very little about its spread throughout Denmark is documented in historical archives,” says Ravneet Sidhu, one of the study’s lead authors and a graduate student at McMaster’s Ancient DNA Centre, where the analysis was conducted.

The McMaster researchers, working with a team of historians and bioarchaeologists in Denmark and Manitoba, performed an in-depth examination of the relatedness and differences between the different strains of plague that were present in Denmark during this time.

They reconstructed and sequenced the genomes of Y. pestis, using fragments teased from ancient teeth, which can preserve traces of blood-borne infection for centuries. They compared the plague genomes to one another and to their modern-day relatives.

Researchers found positive plague samples in 13 individuals who had lived and died over a period of three centuries.

Nine of those samples provided enough genetic information to draw evolutionary conclusions about the plague’s persistence in Denmark. The results create a picture of urban and rural populations hammered by relentless waves of plague.

“The high frequency of Y. pestis reintroduction to Danish communities is consistent with the assumption that most deaths in the period were due to newly introduced pathogens. This association between pathogen introduction and mortality illuminates essential aspects of the demographic evolution, not only in Denmark but across the whole European continent,” says Jesper L. Boldsen, the skeletal collection curator and paleodemographer at ADBOU, University of Southern Denmark.

The analysis, reported today in the journal Current Biology, revealed that the Danish Y. pestis sequences were interspersed with medieval and early modern strains from other European countries, including the Baltic region and Russia, rather than coming from a single domestic cluster that re-emerged from natural reservoirs over the centuries.

“The evidence for plague in Denmark, both historical and archaeological, has been far more sparse than in some other regions, such as England and Italy. This study identified plague for the first time from medieval Denmark, therefore enabling us to connect the experience in Denmark to disease patterns elsewhere,” said Julia Gamble a co-author on the study and assistant professor of anthropology at the University of Manitoba.

In striking detail, researchers describe the earliest known appearance of Y. pestis in Denmark in the town of Ribe dating back to 1333 during the Black Death, its appearance in rural areas such Tirup—where there is no surviving historical evidence—and its disappearance by 1649.

Most places it hit in Denmark were port cities, but one of the last outbreaks struck a small rural site in the centre of the country with no access to water, suggesting importation via land.

Plague is a disease of rodents, but clearly the results suggest human-facilitated movement of plague, either via rodents travelling with humans or via other vectors, such as lice, on them.

“The results reveal new connections between past and present experiences of plague, and add to our understanding of the distribution, patterns and virulence of re-emerging diseases,” says Hendrik Poinar, senior author of the paper, director of the McMaster Ancient DNA Centre and an investigator with the Michael G. DeGroote Institute for Infectious Disease Research.

“We can use this study and the methods we employed for the study of future pandemics,” he says.

Attention editors: Visual assets for media are available below

Photo gallery: https://photos.app.goo.gl/teRpEKYACx6jZUYp9

McMaster Ancient DNA Centre b-roll: https://tinyurl.com/49j3mzpk

END

Deadly waves: Researchers document evolution of plague over hundreds of years in medieval Denmark

Longitudinal study reveals Yersinia pestis, the bacteria that causes plague, was reintroduced into the population again and again

2023-02-24

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Current air pollution standards tied to higher heart risks

2023-02-24

OAKLAND, Calif. — Long-term exposure to air pollution is tied to an increased risk of having a heart attack or dying from heart disease — with the greatest harms impacting under-resourced communities, new Kaiser Permanente research shows.

The study, published February 24 in JAMA Network Open, is one of the largest to date to look at the effects of long-term exposure to fine particle air pollution, which is emitted from sources such as vehicles, smokestacks, and fires. Fine particle air pollution, also known as PM2.5, are fine particles that are 2.5 micrometers in diameter or smaller. The ...

Comparing transmission of COVID-19 in nightlife, household, health care settings

2023-02-24

About The Study: In this case series study that analyzed 44,000 confirmed COVID-19 cases in Tokyo, cases identified in nightlife settings were associated with a higher likelihood of spreading COVID-19 than household and health care cases. Surveillance and interventions targeting nightlife settings should be prioritized to disrupt COVID-19 transmission, especially in the early stage of an epidemic.

Authors: Michihiko Yoshida, Ph.D., of the Minato Public Health Center in Tokyo, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.0589)

Editor’s ...

Association of long-term exposure to particulate air pollution with cardiovascular events

2023-02-24

About The Study: In this study including 3.7 million adults in California, long-term fine particulate air pollution (PM2.5) exposure at moderate concentrations was associated with increased risks of heart attack, ischemic heart disease mortality and cardiovascular disease mortality. The findings add to the evidence that the current regulatory standard is not sufficiently protective.

Authors: Stacey E. Alexeeff, Ph.D., of the Kaiser Permanente Division of Research in Oakland, California, is the corresponding author.

To access ...

Common pregnancy complications may slow development of infant in the womb, study finds

2023-02-24

Gestational diabetes and preeclampsia may be linked to slower biological development in infants, according to a new study led by USC.

The research, published today in JAMA Network Open, found that newborns exposed to these two pregnancy complications were biologically younger than their chronologic gestational age. The infants’ biological or “epigenetic” age is based on molecular markers in their cells.

The results raise intriguing questions about how common pregnancy complications may affect infants and health outcomes later in childhood. Could they create developmental delays? Could some exposures advance biological ...

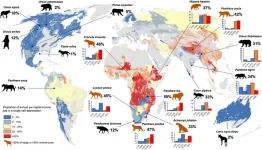

Developing countries pay the highest price for living with large carnivores

2023-02-24

A team of researchers has highlighted human-wildlife conflict as one of the globe’s most pressing human development and conservation dilemmas.

New research published in Communications Biology looked at 133 countries where 18 large carnivores ranged, and found that a person farming with cattle in developing countries such as Kenya, Uganda or India were up to eight times more economically vulnerable than those living in developed economies such as Sweden, Norway or the U.S.

Duan Biggs from Northern Arizona University’s School of Earth and Sustainability is the senior author of the study. He partnered with organizations throughout the world to conduct ...

Head injuries could be a risk factor for developing brain cancer

2023-02-24

Researchers from the UCL Cancer Institute have provided important molecular understanding of how injury may contribute to the development of a relatively rare but often aggressive form of brain tumour called a glioma.

Previous studies have suggested a possible link between head injury and increased rates of brain tumours, but the evidence is inconclusive. The UCL team have now identified a possible mechanism to explain this link, implicating genetic mutations acting in concert with brain tissue inflammation to change the behaviour of cells, making them more likely to become cancerous. Although this study was largely carried out in mice, it suggests ...

New study reveals biodiversity loss drove ecological collapse after the “Great Dying”

2023-02-24

SAN FRANCISCO, CA (February 24, 2023) — The history of life on Earth has been punctuated by several mass extinctions, the greatest of these being the Permian-Triassic extinction event, also known as the “Great Dying”, which occurred 252 million years ago. While scientists generally agree on its causes, exactly how this mass extinction unfolded—and the ecological collapse that followed—remains a mystery. In a study published today in Current Biology, researchers analyzed marine ecosystems before, during, and after the Great Dying ...

Differences in animal biology can affect cancer drug development

2023-02-24

A small but significant metabolic difference between human and mouse lung tumor cells, has been discovered by Weill Cornell Medicine researchers, explaining a discrepancy in previous study results, and pointing toward new strategies for developing cancer treatments.

The work, published Jan. 30 in Cancer Discovery, focuses on lung adenocarcinoma, a common but often difficult to treat cancer that researchers have long studied in mouse models. However, those models didn’t quite align with human clinical observations in some instances. The new paper shows why; a specific gene mutation has opposite effects on tumor ...

Manchester research captures and separates important toxic air pollutant

2023-02-24

Led by scientists at The University of Manchester, a series of new stable, porous materials that capture and separate benzene have been developed. Benzene is a volatile organic compound (VOC) and is an important feedstock for the production of many fine chemicals, including cyclohexane. But, it also poses a serious health threat to humans when it escapes into the air and is thus regarded as an important air pollutant.

The research published today in journal Chem, demonstrates the high adsorption of benzene at low pressures and concentrations, as well as the efficient separation of benzene and cyclohexane. This was achieved by the design and successful preparation ...

Using the power of artificial intelligence, new open-source tool simplifies animal behavior analysis

2023-02-24

Graphic

A team from the University of Michigan has developed a new software tool to help researchers across the life sciences more efficiently analyze animal behaviors.

The open-source software, LabGym, capitalizes on artificial intelligence to identify, categorize and count defined behaviors across various animal model systems.

Scientists need to measure animal behaviors for a variety of reasons, from understanding all the ways a particular drug may affect an organism to mapping how circuits in the brain communicate to produce a particular behavior.

Researchers ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Do prostate cancer drugs interact with certain anticoagulants to increase bleeding and clotting risks?

Many patients want to talk about their faith. Neurologists often don't know how.

AI disclosure labels may do more harm than good

The ultra-high-energy neutrino may have begun its journey in blazars

Doubling of new prescriptions for ADHD medications among adults since start of COVID-19 pandemic

“Peculiar” ancient ancestor of the crocodile started life on four legs in adolescence before it began walking on two

AI can predict risk of serious heart disease from mammograms

New ultra-low-cost technique could slash the price of soft robotics

Increased connectivity in early Alzheimer’s is lowered by cancer drug in the lab

Study highlights stroke risk linked to recreational drugs, including among young users

Modeling brain aging and resilience over the lifespan reveals new individual factors

ESC launches guidelines for patients to empower women with cardiovascular disease to make informed pregnancy health decisions

Towards tailor-made heat expansion-free materials for precision technology

New research delves into the potential for AI to improve radiology workflows and healthcare delivery

Rice selected to lead US Space Force Strategic Technology Institute 4

A new clue to how the body detects physical force

Climate projections warn 20% of Colombia’s cocoa-growing areas could be lost by 2050, but adaptation options remain

New poll: American Heart Association most trusted public health source after personal physician

New ethanol-assisted catalyst design dramatically improves low-temperature nitrogen oxide removal

New review highlights overlooked role of soil erosion in the global nitrogen cycle

Biochar type shapes how water moves through phosphorus rich vegetable soils

Why does the body deem some foods safe and others unsafe?

Report examines cancer care access for Native patients

New book examines how COVID-19 crisis entrenched inequality for women around the world

Evolved robots are born to run and refuse to die

Study finds shared genetic roots of MS across diverse ancestries

Endocrine Society elects Wu as 2027-2028 President

Broad pay ranges in job postings linked to fewer female applicants

How to make magnets act like graphene

The hidden cost of ‘bullshit’ corporate speak

[Press-News.org] Deadly waves: Researchers document evolution of plague over hundreds of years in medieval DenmarkLongitudinal study reveals Yersinia pestis, the bacteria that causes plague, was reintroduced into the population again and again