(Press-News.org) Hydrogen’s potential as a clean fuel could be limited by a chemical reaction in the lower atmosphere, according to research from Princeton University and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association.

This is because hydrogen gas easily reacts in the atmosphere with the same molecule primarily responsible for breaking down methane, a potent greenhouse gas. If hydrogen emissions exceed a certain threshold, that shared reaction will likely lead to methane accumulating in the atmosphere — with decades-long climate consequences.

“Hydrogen is theoretically the fuel of the future,” said Matteo Bertagni, a postdoctoral researcher at the High Meadows Environmental Institute working on the Carbon Mitigation Initiative. “In practice, though, it poses many environmental and technological concerns that still need to be addressed.”

Bertagni is the first author of a research article published in Nature Communications, in which researchers modeled the effect of hydrogen emissions on atmospheric methane. They found that above a certain threshold, even when replacing fossil fuel usage, a leaky hydrogen economy could cause near-term environmental harm by increasing the amount of methane in the atmosphere. The risk for harm is compounded for hydrogen production methods using methane as an input, highlighting the critical need to manage and minimize emissions from hydrogen production.

“We have a lot to learn about the consequences of using hydrogen, so the switch to hydrogen, a seemingly clean fuel, doesn’t create new environmental challenges,” said Amilcare Porporato, Thomas J. Wu ’94 Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering and the High Meadows Environmental Institute. Porporato is a principal investigator and member of the Leadership Team for the Carbon Mitigation Initiative and is also associated faculty at the Andlinger Center for Energy and the Environment.

The problem boils down to one small, difficult-to-measure molecule known as the hydroxyl radical (OH). Often dubbed “the detergent of the troposphere,” OH plays a critical role in eliminating greenhouse gases such as methane and ozone from the atmosphere.

The hydroxyl radical also reacts with hydrogen gas in the atmosphere. And since a limited amount of OH is generated each day, any spike in hydrogen emissions means that more OH would be used to break down hydrogen, leaving less OH available to break down methane. As a consequence, methane would stay longer in the atmosphere, extending its warming impacts.

According to Bertagni, the effects of a hydrogen spike that might occur as government incentives for hydrogen production expand could have decades-long climate consequences for the planet.

“If you emit some hydrogen into the atmosphere now, it will lead to a progressive build-up of methane in the following years,” Bertagni said. “Even though hydrogen only has a lifespan of around two years in the atmosphere, you’ll still have the methane feedback from that hydrogen in 30 years from now.”

In the study, the researchers identified the tipping point at which hydrogen emissions would lead to an increase in atmospheric methane and thereby undermine some of the near-term benefits of hydrogen as a clean fuel. By identifying that threshold, the researchers established targets for managing hydrogen emissions.

“It’s imperative that we are proactive in establishing thresholds for hydrogen emissions, so that they can be used to inform the design and implementation of future hydrogen infrastructure,” said Porporato.

For hydrogen referred to as green hydrogen, which is produced by splitting water into hydrogen and oxygen using electricity from renewable sources, Bertagni said that the critical threshold for hydrogen emissions sits at around 9%. That means that if more than 9% of the green hydrogen produced leaks into the atmosphere — whether that be at the point of production, sometime during transport, or anywhere else along the value chain — atmospheric methane would increase over the next few decades, canceling out some of the climate benefits of switching away from fossil fuels.

And for blue hydrogen, which refers to hydrogen produced via methane reforming with subsequent carbon capture and storage, the threshold for emissions is even lower. Because methane itself is the primary input for the process of methane reforming, blue hydrogen producers have to consider direct methane leakage in addition to hydrogen leakage. For example, the researchers found that even with a methane leakage rate as low as 0.5%, hydrogen leakages would have to be kept under around 4.5% to avoid increasing atmospheric methane concentrations.

“Managing leakage rates of hydrogen and methane will be critical,” Bertagni said. “If you have just a small amount of methane leakage and a bit of hydrogen leakage, then the blue hydrogen that you produce really might not be much better than using fossil fuels, at least for the next 20 to 30 years.”

The researchers emphasized the importance of the time scale over which the effect of hydrogen on atmospheric methane is considered. Bertagni said that in the long-term (over the course of a century, for instance), the switch to a hydrogen economy would still likely deliver net benefits to the climate, even if methane and hydrogen leakage levels are high enough to cause near-term warming. Eventually, he said, atmospheric gas concentrations would reach a new equilibrium, and the switch to a hydrogen economy would demonstrate its climate benefits. But before that happens, the potential near-term consequences of hydrogen emissions might lead to irreparable environmental and socioeconomic damage.

Thus, if institutions hope to meet mid-century climate goals, Bertagni cautioned that hydrogen and methane leakage to the atmosphere must be held in check as hydrogen infrastructure begins to roll out. And because hydrogen is a small molecule that is notoriously difficult to control and measure, he explained that managing emissions will likely require researchers to develop better methods for tracking hydrogen losses across the value chain.

“If companies and governments are serious about investing money to develop hydrogen as a resource, they have to make sure they are doing it correctly and efficiently,” Bertagni said. “Ultimately, the hydrogen economy has to be built in a way that won’t counteract the efforts in other sectors to mitigate carbon emissions.”

The article, “Risk of the hydrogen economy for atmospheric methane,” was published Dec. 13, 2022 in Nature Communications. In addition to Bertagni and Porporato, co-authors include Stephen Pacala of Princeton University and Fabien Paulot, a scientist at the Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association. The research was supported by the National Science Foundation, BP through the Carbon Mitigation Initiative, and the Moore Foundation.

END

Switching to hydrogen fuel could prolong the methane problem

2023-03-13

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Normalizing tumor blood vessels may improve immunotherapy against brain cancer

2023-03-13

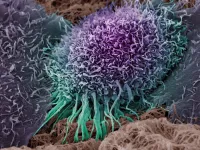

BOSTON – A type of immune therapy called chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cell therapy has revolutionized the treatment of multiple types of blood cancers but has shown limited efficacy against glioblastoma—the deadliest type of primary brain cancer—and other solid tumors.

New research led by investigators at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) and published in the Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer March 10, 2023, suggests that drugs that correct abnormalities in a solid tumor’s blood vessels can improve the delivery and function of CAR-T cell therapy.

With CAR-T cell therapy, immune cells are taken from a ...

Wayne State researchers develop new technology to easily detect active TB

2023-03-13

DETROIT – A team of faculty from Wayne State University has discovered new technology that will quickly and easily detect active Mycobacterium tuberculosis (TB) infection antibodies. Their work, “Discovery of Novel Transketolase Epitopes and the Development of IgG-Based Tuberculosis Serodiagnostics,” was published in a recent edition of Microbiology Spectrum, a journal published by the American Society for Microbiology. The team is led by Lobelia Samavati, M.D., professor in the Center for Molecular Medicine and Genetics in the School of Medicine. ...

Mahoney Life Sciences Prize awarded to UMass Amherst biologist Lynn Adler

2023-03-13

AMHERST, Mass. – University of Massachusetts Amherst biologist Lynn Adler has won the Mahoney Life Sciences Prize for her research demonstrating that different kinds of wildflowers can have markedly different effects on the health and reproduction rate of bumblebees.

“My lab studies the role that flowers play in pollinator health and disease transmission,” says Adler. “Flowers are of course a food source for pollinators, but, in some cases, nectar or pollen from specific plants can be medicinal. However, flowers are also high-traffic areas, and just like with humans, high-traffic areas can be hotspots for disease transmission. We’re tracing how different populations ...

Research highlights gender bias persistence over centuries

2023-03-13

New research from Washington University in St. Louis provides evidence that modern gender norms and biases in Europe have deep historical roots dating back to the Middle Ages and beyond, suggesting that DNA is not the only thing we inherit from our ancestors.

The findings — published on March 13, 2023 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) — highlight why gender norms have remained stubbornly persistent in many parts of the world despite significant strides made by the international ...

Swan populations grow 30 times faster in nature reserves

2023-03-13

Populations of whooper swans grow 30 times faster inside nature reserves, new research shows.

Whooper swans commonly spend their winters in the UK and summers in Iceland.

In the new study, researchers examined 30 years of data on swans at 22 UK sites – three of which are nature reserves managed by the Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust (WWT).

Survival rates were significantly higher at nature reserves, and population growth was so strong that many swans moved to non-protected sites.

Based on these findings, the research team – led by the universities of Exeter and Helsinki – project that nature reserves could help double the number ...

FSU researchers find decaying biomass in Arctic rivers fuels more carbon export than previously thought

2023-03-13

The cycling of carbon through the environment is an essential part of life on the planet.

Understanding the various sources and reservoirs of carbon is a major focus of Earth science research. Plants and animals use the element for cellular growth. It can be stored in rocks and minerals or in the ocean. Carbon in the form of carbon dioxide can move into the atmosphere, where it contributes to a warming planet.

A new study led by Florida State University researchers found that plants and small organisms in Arctic rivers could be responsible for more than half the particulate organic matter flowing to the Arctic Ocean. That’s a significantly ...

Statins may reduce heart disease in people with sleep apnea

2023-03-13

NEW YORK, NY (March 13, 2023)--A new study by Columbia University researchers suggests that cholesterol-lowering drugs called statins have the potential to reduce heart disease in people with obstructive sleep apnea regardless of the use of CPAP machines during the night.

CPAP (continuous positive airway pressure) therapy improves sleep quality and reduces daytime fatigue in people with obstructive sleep apnea. But based on findings from several recent clinical trials, CPAP does not improve heart health as physicians originally hoped.

Alternative ...

New process could capture carbon dioxide equivalent to forest the size of Germany

2023-03-13

New research suggests that around 0.5% of global carbon emissions could be captured during the normal crushing process of rocks commonly used in construction, by crushing them in CO2 gas.

The paper ‘Mechanochemical processing of silicate rocks to trap CO2’ published in Nature Sustainability says that almost no additional energy would be required to trap the CO2. 0.5% of global emissions would be the equivalent to planting a forest of mature trees the size of Germany.

The materials and construction industry ...

City or country living? Research reveals psychological differences

2023-03-13

Living in the country, in rural areas, has long been idealized as a pristine place to raise a family. After all, open air and room to run free pose distinct advantages. But new findings from a University of Houston psychology study indicate that Americans who live in more rural areas tend to be more anxious and depressed, as well as less open-minded and more neurotic. The study also revealed those living in the country were not more satisfied with their lives nor did they have more purpose, or meaning in life, than people who lived in urban areas.

The ...

A potential new target for head and neck cancer immunotherapy

2023-03-13

Researchers at University of California San Diego School of Medicine and Moores Cancer Center at UC San Diego Health have identified a strong association between the product of a gene expressed in most cancers, including the most common type of head and neck cancer, and elevated levels of white blood cells that produce antibodies within tumors.

The findings, published in the March 10, 2023 issue of PNAS Nexus, suggest a potential new target and approach for cancer immunotherapies that have thus far produced mixed results for certain head and ...