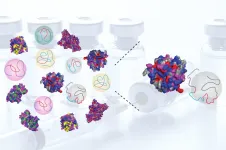

(Press-News.org) Most life on Earth is based on polymers of 20 amino acids that have evolved into hundreds of thousands of different, highly specialized proteins. They catalyze reactions, form backbone and muscle and even generate movement.

But is all that variety necessary? Could biology work just as well with fewer building blocks and simpler polymers?

Ting Xu, a University of California, Berkeley, polymer scientist, thinks so. She has developed a way to mimic specific functions of natural proteins using only two, four or six different building blocks — ones currently used in plastics — and found that these alternative polymers work as well as the real protein and are a lot easier to synthesize than trying to replicate nature's design.

As a proof of concept, she used her design method, which is based on machine learning or artificial intelligence, to synthesize polymers that mimic blood plasma. The artificial biological fluid kept natural protein biomarkers intact without refrigeration and even made the natural proteins more resistant to high temperatures — an improvement over real blood plasma.

The protein substitutes, or random heteropolymers (RHP), could be a game-changer for biomedical applications, since a lot of effort today is put into tweaking natural proteins to do things they were not originally designed to do, or trying to recreate the 3D structure of natural proteins. Drug delivery of small molecules that mimic natural human proteins is one hot research field.

Instead, AI could pick the right number, type and arrangement of plastic building blocks — similar to those used in dental fillings, for example — to mimic the desired function of a protein, and simple polymer chemistry could be used to make it.

In the case of blood plasma, for example, the artificial polymers were designed to dissolve and stabilize natural protein biomarkers in the blood. Xu and her team also created a mix of synthetic polymers to replace the guts of a cell, the so-called cytosol. In a test tube filled with artificial biological fluid, the cell's nanomachines, the ribosomes, continued to pump out natural proteins as if they didn't care whether the fluid was natural or artificial.

"Basically, all the data shows that we can use this design framework, this philosophy, to generate polymers to a point that the biological system would not be able to recognize if it is a polymer or if it is a protein," said Xu, UC Berkeley professor of chemistry and of materials science and engineering. "We basically fool the biology. The whole idea is that if you really design it and inject your plastics as a part of an ecosystem, they should behave like a protein. If the other proteins are like, 'Okay, you are part of us,' then that's OK."

The design framework also opens the door to designing hybrid biological systems, where plastic polymers interact smoothly with natural proteins to improve a system, such as photosynthesis. And the polymers could be made to naturally degrade, making the system recyclable and sustainable.

"You start to think about a completely new future of plastic, instead of all this commodity stuff," said Xu, who is also a faculty scientist at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

She and her colleagues published their results in the March 8 issue of the journal Nature.

A happy mix of biological and abiological polymers

Xu sees living tissue as a complex mix of proteins that evolved to work together flexibly, with less attention paid to the actual amino acid sequence of each protein than to the functional subunits of the protein, the places where these proteins interact. Just as in a lock-and-key mechanism, where it doesn't make much difference whether the key is aluminum or steel, so the actual composition of the functional subunits is less important than what they do.

And since these natural protein mixtures evolved randomly over millions of years, it should be possible to create similar mixtures randomly, with a different alphabet of building blocks, if you use the right principles to design and select them, relieving scientists of the need to recreate the exact protein mixtures in living tissue.

"Nature doesn't do a lot of bottom-up, molecular, precision-driven design like we do in the lab," Xu said. "Nature needs flexibility in order to get where it is. Nature doesn't say, let's study the structure of this virus and make an antigen to attack it. It's going to express a library of antigens and from there pick the one that works."

That randomness can be leveraged to design synthetic polymers that mix well with natural proteins, creating biocompatible plastics more easily than today's targeted techniques, Xu says.

Working with applied statistician Haiyan Huang, a UC Berkeley professor, the researchers developed deep learning methods to match natural protein properties with plastic polymer properties in order to design an artificial polymer that functions similarly, but not identically, to the natural protein. For example, in trying to design a fluid that stabilizes specific natural proteins, the most important properties of the fluid are the electric charges of the polymer subunits and whether or not these subunits like to interact with water — that is, whether they are hydrophilic or hydrophobic. The synthetic polymers were designed to match those properties, but not other characteristics of the natural proteins in the fluid.

Huang and graduate student Shuni Li trained the deep learning technique — a hybrid of classical artificial intelligence (AI) that Huang refers to as a modified variational autoencoder (VAE) — on a database of about 60,000 natural proteins. These proteins were broken down into 50-amino acid segments, and the segment properties were compared to those of artificial polymers composed of only four building blocks.

With feedback from experiments by graduate student Zhiyuan Ruan in Xu's lab, the team was able to chemically synthesize a random group of polymers, RHPs, that mimicked the natural proteins in terms of charge and hydrophobicity.

"We look at the sequence space that nature has already designed, we analyze it, we make the polymer match to what nature already evolved, and they work," Xu said. "How well you follow the protein sequence determines the performance of the polymer you get. Extracting information from an established system, such as naturally occurring proteins, is the easiest shortcut to enable us to tease out the right criteria for creating biologically compatible polymers."

Colleagues in the lab of Carlos Bustamante, UC Berkeley professor of molecular and cell biology, of chemistry and of physics, performed single molecule optical tweezers studies and clearly showed that the RHPs can mimic how proteins behave.

Xu, Huang and their colleagues are now trying to mimic other protein characteristics to reproduce in plastic the many other functions of natural amino acid polymers.

"Right now, our goal is simply stabilizing proteins and mimicking the most basic protein functions," Huang said. "But with a more refined design of the RHP system, I think it's natural for us to explore enhancing other functions. We are trying to study what sequence compositions can be informative regarding the possible protein functions or behavior that the RHP can carry."

The design platform opens the door to hybrid systems of natural and synthetic polymers, but also suggests ways to more easily make biocompatible materials, from artificial tears or cartilage to coatings that can be used to deliver drugs.

"If you want to develop biomaterials to interact with your body, to do tissue engineering or drug delivery, or you want to do a stent coating, you have to be compatible with biological systems," Xu said. "What this paper is telling you is: Here are the design rules. This is how you should interface with biological fluids."

Her ultimate goal is to totally rethink how biomaterials are currently designed, because current methods — focused primarily on mimicking the amino acid structures of natural proteins — are not working.

"The Food and Drug Administration hasn't approved any new material for polymer biomaterials for decades, and I think the reason is that a lot of synthetic polymers are not really working — we are pursuing the wrong direction," she said. "We are not letting the biology tell us how the material should be designed. We are looking at individual pathways, individual factors, and not looking at it holistically. The biology is really complicated, but it's very random. You really have to speak the same language when dealing with materials. That's what I want to share with the materials community."

Other co-authors of the paper include UC Berkeley graduate students Alexandra Grigoropoulos, Haotian Chen and Ivan Jayapurna; UC Berkeley postdoctoral fellows Hossein Amiri and Tao Jiang; UC Berkeley undergraduate student Zhaoyi Gu; and Xu’s collaborators at MIT, Alfredo Alexander-Katz and Shayna Hilburg.

The work was funded by the U.S. Department of Defense (W911NF-13-1-0232, HDTRA1-19-1-0011), the National Science Foundation (DMR- 2104443), the Department of Energy's Office of Science (DE-AC02-05-CH11231) and the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation's Matter-to-Life initiative.

END

Can synthetic polymers replace the body's natural proteins?

Using AI, synthesized random heteropolymers mimic proteins in blood serum, cell's cytosol

2023-03-20

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

The dark figure of crime

2023-03-20

AMES, IA – In his new book, Matt DeLisi, a world-renowned criminologist at Iowa State University, lays out evidence that Ted Bundy’s criminal career was far lengthier and deadlier than the official record from 1974 to 1978.

“Ted Bundy and the Unsolved Murder Epidemic: The Dark Figure of Crime” underscores how most crime is never known to law enforcement. The book also emphasizes that a small percentage of individuals in society commit a much larger share of violent crime. With an estimated 250,000 to 350,000 unsolved homicide cases in the U.S., DeLisi offers solutions ...

JMIR Medical Education invites submissions for its new theme issue "ChatGPT: Generative Language Models and Generative AI in Medical Education"

2023-03-20

JMIR Medical Education is excited to announce the launch of a new theme issue, ChatGPT, Generative Language Models, and Generative AI in Medical Education. The Call for Papers is now open and submissions are due by July 31st.

Guest editors Kaushik P Venkatesh, MBA, MPH, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA, and Maged N Kamel Boulos, MBBCh, MSc, PhD, FHEA, SMIEEE, of Sun Yat-sen University, China, are encouraging both empirical and theoretical submissions, including original research, systematic reviews, viewpoints, and tutorials.

The objective of this theme issue ...

Few people seem to find real joy in JOMO

2023-03-20

PULLMAN, Wash. – Most people who ranked high in “joy of missing out” or JOMO also reported high levels of social anxiety in a recent Washington State University-led study.

The term JOMO has been popularized as a healthy enjoyment of solitude in almost direct opposition to the negative FOMO, the “fear of missing out” people may have when seeing others having fun experiences without them. In an analysis of two samples of adults, researchers found mixed results when it comes to JOMO with evidence that there is some anxiety behind the joy.

“In general, a lot of people like being connected,” said ...

Does discrimination accelerate aging in African American cancer survivors?

2023-03-20

Study reveals link between major discrimination and frailty

Cancer and its treatment can accelerate the rate of aging because they both destabilize and damage biological systems in the body. New research published by Wiley online in CANCER, a peer-reviewed journal of the American Cancer Society, found that African American cancer survivors who reported high levels of discrimination exhibited greater aging and frailty than those reporting lower levels of discrimination.

For the study, Jeanne Mandelblatt, MD, MPH, director of the Institute for Cancer and Aging Research at Georgetown University’s Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center in Washington, ...

Study finds relationship between discrimination and frailty in Black cancer survivors

2023-03-20

WASHINGTON — Discrimination experienced by Black people can affect their health and increase their frailty, which can be particularly impactful for cancer survivors, according to a new study by researchers at Georgetown University’s Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center and colleagues at the Barbara Ann Karmanos Cancer Institute in Detroit. The researchers assessed frailty by a number of factors, including whether a participant had several chronic diseases, poor muscle strength and difficulty performing activities of daily living.

The ...

Underactive immune response may explain obesity link to COVID-19 severity

2023-03-20

Individuals who are obese may be more susceptible to severe COVID-19 because of a poorer inflammatory immune response, say Cambridge scientists.

Scientists at the Cambridge Institute of Therapeutic Immunology and Infectious Disease (CITIID) and Wellcome Sanger Institute showed that following SARS-CoV-2 infection, cells in the lining of the lungs, nasal cells, and immune cells in the blood show a blunted inflammatory response in obese patients, producing suboptimal levels of molecules needed to fight ...

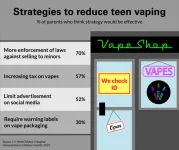

Unrealistic vaping views? Nearly ½ of parents confident they’d know if their child vapes

2023-03-20

Nearly half of parents say they would definitely know if their child was vaping, despite characteristics of vaping devices that make it easy to hide or disguise their use, a new national poll suggests.

Four in five parents also think their adolescent or teen understands the health risks of vaping with few believing their child has tried it, according to the C.S. Mott Children’s Hospital National Poll on Children’s Health at University of Michigan Health.

“Very few parents believe their ...

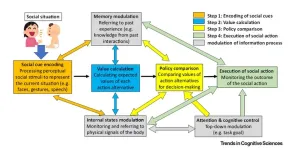

Changing one’s behavior in different social interactions is child's play

2023-03-20

Society and social interaction play a key role in life for humans. The well-being of a person greatly depends upon their ability to be part of complex socio-cultural institutions. Even during infancy, humans rely on their social interactions with other humans for social and cultural learning, subsequent adaptation to different social environments, and ultimately, survival. Several studies have shown that infants do not respond automatically or reflexively to external cues, but instead adaptively modulate their social behaviors to suit their social context. Gaze-following is one such behavior that infants modulate based on their surroundings. ...

Financial landlords own four times more rental units than previously thought

2023-03-20

New research indicates that a small percentage of financial landlords, like private equity firms and institutional investors, own four times more of Montreal’s rental housing stock than was previously estimated. Neighbourhoods with more financial landlords are also experiencing higher housing stress levels.

In the first comprehensive analysis of its kind in a North American city, researchers from the University of Waterloo and McGill University developed a new method of identifying networks of property ownership lurking behind ...

Multi-drug resistant organisms can be transmitted between healthy dogs and cats and their hospitalised owners

2023-03-19

**Note: the release below is a special early release from the European Congress of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases (ECCMID 2023, Copenhagen, 15-18 April). Please credit the conference if you use this story**

Embargo: 2301H UK time Saturday 18 March

Healthy dogs and cats could be passing on multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs; bacteria that resist treatment with more than one antibiotic) to their hospitalised owners, and likewise humans could be transmitting these dangerous microbes to their pets, according to new research being presented ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

National poll finds gaps in community preparedness for teen cardiac emergencies

One strategy to block both drug-resistant bacteria and influenza: new broad-spectrum infection prevention approach validated

Survey: 3 in 4 skip physical therapy homework, stunting progress

College students who spend hours on social media are more likely to be lonely – national US study

Evidence behind intermittent fasting for weight loss fails to match hype

How AI tools like DeepSeek are transforming emotional and mental health care of Chinese youth

Study finds link between sugary drinks and anxiety in young people

Scientists show how to predict world’s deadly scorpion hotspots

ASU researchers to lead AAAS panel on water insecurity in the United States

ASU professor Anne Stone to present at AAAS Conference in Phoenix on ancient origins of modern disease

Proposals for exploring viruses and skin as the next experimental quantum frontiers share US$30,000 science award

ASU researchers showcase scalable tech solutions for older adults living alone with cognitive decline at AAAS 2026

Scientists identify smooth regional trends in fruit fly survival strategies

Antipathy toward snakes? Your parents likely talked you into that at an early age

Sylvester Cancer Tip Sheet for Feb. 2026

Online exposure to medical misinformation concentrated among older adults

Telehealth improves access to genetic services for adult survivors of childhood cancers

Outdated mortality benchmarks risk missing early signs of famine and delay recognizing mass starvation

Newly discovered bacterium converts carbon dioxide into chemicals using electricity

Flipping and reversing mini-proteins could improve disease treatment

Scientists reveal major hidden source of atmospheric nitrogen pollution in fragile lake basin

Biochar emerges as a powerful tool for soil carbon neutrality and climate mitigation

Tiny cell messengers show big promise for safer protein and gene delivery

AMS releases statement regarding the decision to rescind EPA’s 2009 Endangerment Finding

Parents’ alcohol and drug use influences their children’s consumption, research shows

Modular assembly of chiral nitrogen-bridged rings achieved by palladium-catalyzed diastereoselective and enantioselective cascade cyclization reactions

Promoting civic engagement

AMS Science Preview: Hurricane slowdown, school snow days

Deforestation in the Amazon raises the surface temperature by 3 °C during the dry season

Model more accurately maps the impact of frost on corn crops

[Press-News.org] Can synthetic polymers replace the body's natural proteins?Using AI, synthesized random heteropolymers mimic proteins in blood serum, cell's cytosol