(Press-News.org) A new study investigates how an extinct, carnivorous marsupial relative with canines so large they extended across the top of its skull could hunt effectively despite having wide-set eyes, like a cow or a horse. The skulls of carnivores typically have forward-facing eye sockets, or orbits, which helps enable stereoscopic (3D) vision, a useful adaptation for judging the position of prey before pouncing. Scientists from the American Museum of Natural History and the Instituto Argentino de Nivología, Glaciología, y Ciencias Ambientales in Mendoza, Argentina, studied whether the “marsupial sabertooth” Thylacosmilus atrox could see in 3D at all. Their results are published today in the journal Communications Biology.

Popularly known as the “marsupial (or metatherian) sabertooth” because its extraordinarily large upper canines recall those of the more famous placental sabertooth that evolved in North America, Thylacosmilus lived in South America until its extinction about 3 million years ago. It was a member of Sparassodonta, a group of highly carnivorous mammals related to living marsupials. Although sparassodont species differed considerably in size—Thylacosmilus may have weighed as much as 100 kilograms (220 pounds)—the great majority resembled placental carnivores like cats and dogs in having forward-facing eyes and, presumably, full 3D vision. By contrast, the orbits of Thylacosmilus, a supposed hypercarnivore—an animal with a diet estimated to consist of at least 70 percent meat—were positioned like those of an ungulate, with orbits that face mostly laterally. In this situation, the visual fields do not overlap sufficiently for the brain to integrate them in 3D. Why would a hypercarnivore evolve such a peculiar adaptation? A team of researchers from Argentina and the United States set out to look for an explanation.

“You can’t understand cranial organization in Thylacosmilus without first confronting those enormous canines,” said lead author Charlène Gaillard, a Ph.D. student in the Instituto Argentino de Nivología, Glaciología, y Ciencias Ambientales (INAGLIA). “They weren’t just large; they were ever-growing, to such an extent that the roots of the canines continued over the tops of their skulls. This had consequences, one of which was that no room was available for the orbits in the usual carnivore position on the front of the face.”

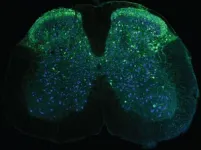

Gaillard used CT scanning and 3D virtual reconstructions to assess orbital organization in a number of fossil and modern mammals. She was able to determine how the visual system of Thylacosmilus would have compared to those in other carnivores or other mammals in general. Although low orbital convergence occurs in some modern carnivores, Thylacosmilus was extreme in this regard: it had an orbital convergence value as low as 35 degrees, compared to that of a typical predator, like a cat, at around 65 degrees.

However, good stereoscopic vision also relies on the degree of frontation, which is a measure of how the eyeballs are situated within the orbits. “Thylacosmilus was able to compensate for having its eyes on the side of its head by sticking its orbits out somewhat and orienting them almost vertically, to increase visual field overlap as much as possible,” said co-author Analia M. Forasiepi, also in INAGLIA and a researcher in CONICET, the Argentinian science and research agency. “Even though its orbits were not favorably positioned for 3D vision, it could achieve about 70 percent of visual field overlap—evidently, enough to make it a successful active predator.”

“Compensation appears to be the key to understanding how the skull of Thylacosmilus was put together,” said study co-author Ross D. E. MacPhee, a senior curator at the American Museum of Natural History. “In effect, the growth pattern of the canines during early cranial development would have displaced the orbits away from the front of the face, producing the result we see in adult skulls. The odd orientation of the orbits in Thylacosmilus actually represents a morphological compromise between the primary function of the cranium, which is to hold and protect the brain and sense organs, and a collateral function unique to this species, which was to provide enough room for the development of the enormous canines.”

Lateral displacement of the orbits was not the only cranial modification that Thylacosmilus developed to accommodate its canines while retaining other functions. Placing the eyes on the side of the skull brings them close to the temporal chewing muscles, which might result in deformation during eating. To control for this, some mammals, including primates, have developed a bony structure that closes off the eye sockets from the side. Thylacosmilus did the same thing—another example of convergence among unrelated species.

This leaves a final question: What purpose would have been served by developing huge, ever-growing teeth that required re-engineering of the whole skull?

“It might have made predation easier in some unknown way,” said Gaillard, “But, if so, why didn’t any other sparassodont—or for that matter, any other mammalian carnivore—develop the same adaptation convergently? The canines of Thylacosmilus did not wear down, like the incisors of rodents. Instead, they just seem to have continued growing at the root, eventually extending almost to the rear of the skull.”

Forasiepi underlined this point, saying, “To look for clear-cut adaptive explanations in evolutionary biology is fun but largely futile. One thing is clear: Thylacosmilus was not a freak of nature, but in its time and place it managed, apparently quite admirably, to survive as an ambush predator. We may view it as an anomaly because it doesn’t fit within our preconceived categories of what a proper mammalian carnivore should look like, but evolution makes its own rules.”

ABOUT THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY (AMNH)

The American Museum of Natural History, founded in 1869, is one of the world’s preeminent scientific, educational, and cultural institutions. The Museum encompasses more than 40 permanent exhibition halls and galleries for temporary exhibitions, the Rose Center for Earth and Space and the Hayden Planetarium, and the Richard Gilder Center for Science, Education, and Innovation, which opens in 2023. The Museum’s scientists draw on a world-class permanent collection of more than 34 million specimens and artifacts, some of which are billions of years old, and on one of the largest natural history libraries in the world. Through its Richard Gilder Graduate School, the Museum grants the Ph.D. degree in Comparative Biology and the Master of Arts in Teaching (MAT) degree, the only such freestanding, degree-granting programs at any museum in the United States. The Museum’s website, digital videos, and apps for mobile devices bring its collections, exhibitions, and educational programs to millions around the world. Visit amnh.org for more information.

END

How the "marsupial sabertooth" thylacosmilus saw its world

Study describes how extinct hypercarnivore likely achieved 3D vision despite wide-set eyes more characteristic of an herbivore than a predator

2023-03-21

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Molecular teamwork makes the organic dream work

2023-03-21

The virus responsible for E. coli infection has a secret weapon: teamwork.

Always scrappy in its bid for survival, the virus alights on an unassuming host cell and grips the surface with the business end of its tubular tail. Then, the proteins in the tail contract in unison, flattening its structure like a stepped-on spring and reeling the virus's body in for the critical strike.

Thanks to the proteins' teamwork, the tail can flex and flatten with ease. This process, called molecular cooperativity, is often observed in nature but rarely ...

Wearable microscopes advance spinal cord imaging in mice

2023-03-21

LA JOLLA—(March 21, 2023) The spinal cord acts as a messenger, carrying signals between the brain and body to regulate everything from breathing to movement. While the spinal cord is known to play an essential role in relaying pain signals, technology has limited scientists’ understanding of how this process occurs on a cellular level. Now, Salk scientists have created wearable microscopes to enable unprecedented insight into the signaling patterns that occur within the spinal cords of mice.

This technological advancement, detailed in two papers published in Nature Communications ...

ACTG announces publication of pivotal hepatitis C study in Clinical Infectious Diseases

2023-03-21

Los Angeles, Calif. – The AIDS Clinical Trials Group (ACTG), the world’s largest HIV research network, is announcing the publication of “Perspectives on Adherence from the ACTG 5360 MINMON Trial: A Minimum Monitoring Approach with 12 Weeks of Sofosbuvir/Velpatasvir in Chronic Hepatitis C Treatment” in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases. This publication found that self-reported 100 percent adherence in the first four weeks of hepatitis C treatment with sofosbuvir/velpatasvir was associated with sustained virologic response (which is when no hepatitis C virus is found in the blood 12 weeks after completing ...

Built environment strongest predictor of adolescent obesity, related health behaviors

2023-03-21

ROCKVILLE, Md.—New research shows that the built environment, not social and economic environments, is a strong predictor of adolescents’ body mass index (BMI), overweight and obesity status, and eating behaviors, according to a new study in Obesity, The Obesity Society’s (TOS) flagship journal. This study provides the first quasi-experimental empirical evidence of these environments on adolescents’ BMI, overweight, obesity and related behaviors.

“Our research suggests that strategies for addressing ...

The Minderoo-Monaco Commission on Plastics and Human Health issues sweeping new report

2023-03-21

Chestnut Hill, Mass (3/21/2023) – Philip Landrigan, MD, director of the Program on Global Public Health and the Common Good and the Boston College Observatory on Planetary Health, is the lead author of a groundbreaking new report about the far-reaching health hazards of plastics manufacturing and pollution across the entire product life cycle. Published in the journal Annals of Global Public Health and released in Monaco during Monaco Ocean Week, the study was undertaken by an international group of scientists ...

Douglas-fir in Klamath Mountains are in ‘decline spiral,’ Oregon State research shows

2023-03-21

CORVALLIS, Ore. – Increases in mortality among Douglas-fir in the Klamath Mountains are the result of multiple factors that have the iconic tree in a “decline spiral” in parts of the region, a new study by the Oregon State University College of Forestry and OSU Extension Service indicates.

Findings, which include a tool landowners and managers can use to assess a stand of trees’ risk as the climate continues to change, were published in the Journal of Forestry.

Douglas-fir, Oregon’s official state tree, is the most abundant tree species in the ...

Cases and transmission of highly contagious fungal infections see dramatic increase between 2019 and 2021

2023-03-21

1. Cases and transmission of highly contagious fungal infections see dramatic increase between 2019 and 2021

Many cases resistant to first-line treatment

Abstract: https://www.acpjournals.org/doi/10.7326/M22-3469

URL goes live when the embargo lifts

A study of national surveillance data found that cases of Candida auris, a highly contagious fungal infection, rose drastically between 2019 and 2021 reflecting increased transmission. The researchers also noted an increase in echinocandin-resistant cases and evidence of transmission, which is particularly concerning because echinocandins are first-line therapy for invasive Candida infections, including C auris. These findings ...

Leading Auckland University researchers elected to NZ Royal Society

2023-03-21

The new Ngā Ahurei a Te Apārangi Fellows have been elected for their distinction in research and advancement of science, technology or the humanities to the highest international standards.

The University of Auckland is New Zealand’s leading research-led university, which Deputy Vice-Chancellor Research, Frank Bloomfield, says is largely due to the quality of its researchers, and the impact their work has within Aotearoa New Zealand and internationally.

“The research and scholarship of our new Fellows is regarded as world leading in their respective areas and as such, they have been recognised by the ...

Almost all countries around the globe criminalise abortion in some circumstances

2023-03-21

Almost all countries around the globe criminalise abortion in some circumstances, despite the public health risks and impact on human rights, finds a review of the scope of penalties for the procedure in 182 nations, published in the open access journal BMJ Global Health.

Some 134 countries penalise those seeking an abortion, while 181 penalise providers, and 159 those who assist in the procedure, the review shows.

The evidence indicates that criminalisation doesn’t deter women from deciding to have an abortion; rather, it limits or delays access to safe abortion and increases the need to turn to unsafe and unregulated services, point out the researchers.

Criminalisation ...

Pregnant women in road traffic collisions at heightened risk of birth complications

2023-03-21

Pregnant women involved in road traffic collisions—even those with minor injuries—are at heightened risk of potentially serious birth complications, including dislodgement of the placenta (placental abruption), very heavy bleeding, and the need for a caesarean section, finds a Taiwanese study published online in the journal Injury Prevention.

And the risks are even higher for those on scooters rather than in cars, the findings indicate.

Road traffic collisions are the leading cause of traumatic injury during pregnancy, with previously published research suggesting they account for up to 70% of such injuries. But most of the evidence base to date on the ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

DGIST identifies “magic blueprint” for converting carbon dioxide into resources through atom-level catalyst design

COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy may help prevent preeclampsia

Menopausal hormone therapy not linked to increased risk of death

Chronic shortage of family doctors in England, reveals BMJ analysis

Booster jabs reduce the risks of COVID-19 deaths, study finds

Screening increases survival rate for stage IV breast cancer by 60%

ACC announces inaugural fellow for the Thad and Gerry Waites Rural Cardiovascular Research Fellowship

University of Oklahoma researchers develop durable hybrid materials for faster radiation detection

Medicaid disenrollment spikes at age 19, study finds

Turning agricultural waste into advanced materials: Review highlights how torrefaction could power a sustainable carbon future

New study warns emerging pollutants in livestock and aquaculture waste may threaten ecosystems and public health

Integrated rice–aquatic farming systems may hold the key to smarter nitrogen use and lower agricultural emissions

Hope for global banana farming in genetic discovery

Mirror image pheromones help beetles swipe right

Prenatal lead exposure related to worse cognitive function in adults

Research alert: Understanding substance use across the full spectrum of sexual identity

Pekingese, Shih Tzu and Staffordshire Bull Terrier among twelve dog breeds at risk of serious breathing condition

Selected dog breeds with most breathing trouble identified in new study

Interplay of class and gender may influence social judgments differently between cultures

Pollen counts can be predicted by machine learning models using meteorological data with more than 80% accuracy even a week ahead, for both grass and birch tree pollen, which could be key in effective

Rewriting our understanding of early hominin dispersal to Eurasia

Rising simultaneous wildfire risk compromises international firefighting efforts

Honey bee "dance floors" can be accurately located with a new method, mapping where in the hive forager bees perform waggle dances to signal the location of pollen and nectar for their nestmates

Exercise and nutritional drinks can reduce the need for care in dementia

Michelson Medical Research Foundation awards $750,000 to rising immunology leaders

SfN announces Early Career Policy Ambassadors Class of 2026

Spiritual practices strongly associated with reduced risk for hazardous alcohol and drug use

Novel vaccine protects against C. diff disease and recurrence

An “electrical” circadian clock balances growth between shoots and roots

Largest study of rare skin cancer in Mexican patients shows its more complex than previously thought

[Press-News.org] How the "marsupial sabertooth" thylacosmilus saw its worldStudy describes how extinct hypercarnivore likely achieved 3D vision despite wide-set eyes more characteristic of an herbivore than a predator