(Press-News.org) Researchers at the Paul Scherrer Institute PSI have deciphered the molecular processes that first occur in the eye when light hits the retina. The processes – which take only a fraction of a trillionth of a second – are essential for human sight. The study has now been published in the scientific journal Nature.

It only involves a microscopic change of a protein in our retina, and this change occurs within an incredibly small time frame: it is the very first step in our light perception and ability to see. It is also the only light-dependent step. PSI researchers have established exactly what happens after the first trillionth of a second in the process of visual perception, with the help of the SwissFEL X-ray free-electron laser of the PSI.

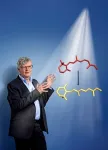

At the heart of the action is our light receptor, the protein rhodopsin. In the human eye it is produced by sensory cells, the rod cells, which specialise in the perception of light. Fixed in the middle of the rhodopsin is a small kinked molecule: retinal, a derivative of vitamin A. When light hits the protein, retinal absorbs part of the energy. With lightning speed, it then changes its three-dimensional form so the switch in the eye is changed from “off” to “on”. This triggers a cascade of reactions whose overall effect is the perception of a flash of light.

Tied – but yet free

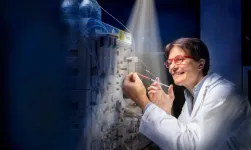

But what happens in detail when retinal transforms from what is known as the 11-cis form into the all-trans form? “We have known about the starting point and the end product of the retinal transformation for some time, but so far no one has been able to observe in real time exactly how the change occurs in the sight pigment rhodopsin,” says Valérie Panneels, a scientist with PSI’s Biology and Chemistry Research Division.

Panneels compares the process to a cat falling back-first from a tree but somehow landing on its feet unharmed. “The question is: what states does the cat adopt during its fall as it rights itself to land on its feet?”

As the PSI scientists discovered, the “retinal cat” starts off by turning the middle of its body. For Valerie Panneels, the “eureka moment” came when she realised something else that occurs: the protein absorbs part of the light energy to briefly inflate a tiny amount – “like our chest expanding when we breathe in, only to contract again shortly afterwards.”

During this “breathing in” stage, the protein temporarily loses most of its contact with the retinal that sits in its middle. “Although the retinal is still connected to the protein at its ends through chemical bonds, it now has room to rotate.” At that moment, the molecule resembles a dog on a loose leash that is free to give a jerk.

Shortly afterwards the protein contracts again and has the retinal firmly back in its grasp, except now in a different more elongated form. “In this way the retinal manages to turn itself, unimpaired by the protein in which it is held.”

One of the fastest natural processes

The transformation of the retinal from 11-cis kinked form into the all-trans elongated form only takes a picosecond, or one trillionth (10-12) of a second, making it one of the fastest processes in all of nature.

The only way of recording and analysing such rapid biological processes is with an X-ray free-electron laser like the SwissFEL. “The SwissFEL allows us to study in detail the fundamental processes of the human body, such as vision,” says Gebhard Schertler, Head of PSI’s Biology and Chemistry Research Division and joint lead author of the study along with Valérie Panneels.

To return to the analogy of the cat, this would be like filming its fall with a high-speed camera, but with one major difference: the filming speed of the SwissFEL camera is a milliard times faster. Working with large research facilities also involves much more than simply pressing a shutter button. The PhD student Thomas Gruhl, who went on to work as a postdoc researcher at the Institute for Structural and Molecular Biology in London, has spent years developing a method of producing high-quality rhodopsin crystals capable of delivering ultra-high resolution data. Ultimately only these data made it possible to perform the necessary measurements at SwissFEL and – before the SwissFEL was built – at the X-ray free-electron laser SACLA in Japan.

This experiment once again shows SwissFEL’s vital role in Swiss research. “It will probably help us come up with many more solutions in future,” says Gebhard Schertler. “Amongst other things, we are also developing methods for investigating dynamic processes in proteins that are not normally activated by light.” The scientists use artificial means to make such molecules responsive to light: either they make appropriate changes to the binding partners or they mix proteins with binding partners in the crystal so quickly that they can be examined at the SwissFEL. In any case, the procedure involved is definitely much more complicated than simply pointing a camera at a cat falling from a tree.

Text: Brigitte Osterath

About PSI

The Paul Scherrer Institute PSI develops, builds and operates large, complex research facilities and makes them available to the national and international research community. The institute's own key research priorities are in the fields of matter and materials, energy and environment and human health. PSI is committed to the training of future generations. Therefore about one quarter of our staff are post-docs, post-graduates or apprentices. Altogether PSI employs 2100 people, thus being the largest research institute in Switzerland. The annual budget amounts to approximately CHF 400 million. PSI is part of the ETH Domain, with the other members being the two Swiss Federal Institutes of Technology, ETH Zurich and EPFL Lausanne, as well as Eawag (Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology), Empa (Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science and Technology) and WSL (Swiss Federal Institute for Forest, Snow and Landscape Research). Insight into the exciting research of the PSI with changing focal points is provided 3 times a year in the publication 5232 - The Magazine of the Paul Scherrer Institute.

Contact

Dr. Valérie Panneels

Biology and Chemistry Research Division

Paul Scherrer Institute, Forschungsstrasse 111, 5232 Villigen PSI, Switzerland

Telephone: +41 56 310 21 04, e-mail: valerie.panneels@psi.ch [German, English, French]

Professor Gebhard Schertler

Head of the Biology and Chemistry Research Division

Paul Scherrer Institute, Forschungsstrasse 111, 5232 Villigen PSI, Switzerland

Telephone: +41 56 310 42 65, e-mail: gebhard.schertler@psi.ch [German, English]

Original publication

Ultrafast structural changes direct the first molecular events of vision

Thomas Gruhl, Tobias Weinert, Matthew Rodrigues, Christopher J Milne, Giorgia Ortolani, Karol Nass, Eriko Nango, Saumik Sen, Philip J M Johnson, Claudio Cirelli, Antonia Furrer, Sandra Mous, Petr Skopintsev, Daniel James, Florian Dworkowski, Petra Baath, Demet Kekilli, Dmitry Ozerov, Rie Tanaka, Hannah Glover, Camila Bacellar, Steffen Brünle, Cecilia M Casadei, Azeglio D Diethelm, Dardan Gashi, Guillaume Gotthard, Ramon Guixà-González, Yasumasa Joti, Victoria Kabanova, Gregor Knopp, Elena Lesca, Pikyee Ma, Isabelle Martiel, Jonas Mühle, Shigeki Owada, Filip Pamula, Daniel Sarabi, Oliver Tejero, Ching-Ju Tsai, Niranjan Varma, Anna Wach, Sébastien Boutet, Kensuke Tono, Przemyslaw Nogly, Xavier Deupi, So Iwata, Richard Neutze, Jörg Standfuss, Gebhard Schertler, Valerie Panneels

Nature, 22.03.2023

DOI: 10.1038/s41586-023-05863-6

END

How vision begins

2023-03-22

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

New NIH study reveals shared genetic markers underlying substance use disorders

2023-03-22

By combing through genomic data of over 1 million people, scientists have identified genes commonly inherited across addiction disorders, regardless of the substance being used. This dataset – one of the largest of its kind – may help reveal new treatment targets across multiple substance use disorders, including for people diagnosed with more than one. The findings also reinforce the role of the dopamine system in addiction, by showing that the combination of genes underlying addiction disorders was also associated with regulation of dopamine signaling.

Published ...

Surprisingly simple explanation for the alien comet 'Oumuamua's weird orbit

2023-03-22

In 2017, a mysterious comet dubbed 'Oumuamua fired the imaginations of scientists and the public alike. It was the first known visitor from outside our solar system, it had no bright coma or dust tail, like most comets, and a peculiar shape — something between a cigar and a pancake — and its small size more befitted an asteroid than a comet.

But the fact that it was accelerating away from the sun in a way that astronomers could not explain perplexed scientists, leading some to suggest that it was an alien spaceship.

Now, a University of California, Berkeley, astrochemist ...

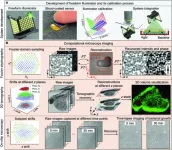

Smaller, denser, better illuminators for computational microscopy

2023-03-22

Seeking to expand the possibilities offered by programmable illumination, a group of researchers at the University of Connecticut developed a strategy for constructing and calibrating freeform illuminators offering greater flexibility for computational microscopy. Their calibration method uses a blood-coated sensor for reconstruction of light source positions. They demonstrated the use of calibrated freeform illuminators for Fourier ptychographic microscopy, 3D tomographic imaging and on-chip microscopy and used a calibrated freeform illuminator in an experiment to track bacterial growth.

The group’s research was published Feb. 20 in Intelligent Computing, a Science ...

Binghamton University reaches highest ever score for LGBTQ+ inclusion

2023-03-22

BINGHAMTON, N.Y. -- Binghamton University, State University of New York scored a nearly perfect ranking on the latest national Campus Pride Index, which measures a university’s commitment to LGBTQ+ safety and inclusivity on campus. The University received a 4.5 out of 5, an increase from the 3.5 scores received in previous years.

Nicholas Martin, assistant director of the LGBTQ Center at Binghamton University, sees this as a reflection of the organization’s dedication and Binghamton’s real commitment to outreach.

“Our ...

Researchers make biodegradable optical components from crab shells

2023-03-22

WASHINGTON — Researchers have developed a process to turn crab shells into a bioplastic that can be used to make optical components known as diffraction gratings. The resulting lightweight, inexpensive gratings are biodegradable and could enable portable spectrometers that are also disposable.

“The Philippines is known for delicious seafood, but this industry is also a source of large amounts of solid waste such as discarded crab shells,” said research team leader Raphael A. Guerrero, from Ateneo de Manila University in the Philippines. “We wanted to find an alternative use for crab shell ...

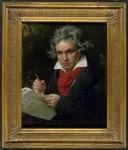

Beethoven’s genome offers clues to composer’s health and family history

2023-03-22

University of Cambridge Media Release

Beethoven’s genome offers clues to composer’s health and family history

UNDER STRICT EMBARGO UNTIL 11:00 US ET / 15:00 UK / 16:00 CET ON WEDNESDAY 22nd MARCH 2023

International team of scientists deciphers renowned composer’s genome from locks of hair.

Study shows Beethoven was predisposed to liver disease, and infected with Hepatitis B, which – combined with his alcohol consumption – may have contributed to his death.

DNA ...

Ludwig von Beethoven’s genome sheds light on chronic health problems and cause of death

2023-03-22

In 1802, Ludwig van Beethoven asked his brothers to request that his doctor, J.A. Schmidt, describe his malady—his progressive hearing loss—to the world upon his death so that "as far as possible at least the world will be reconciled to me after my death." Now, more than two centuries later, a team of researchers reporting in the journal Current Biology on March 22 have partially fulfilled his wish by analyzing DNA they lifted and pieced together from locks of his hair.

“Our primary goal was to shed light on Beethoven’s health problems, which famously include progressive hearing loss, beginning in his mid- to late-20s and eventually leading to him ...

Unusual Toxoplasma parasite strain killed sea otters and could threaten other marine life

2023-03-22

Scientists in California are raising the alarm about a newly reported form of toxoplasmosis that kills sea otters and could also infect other animals and people. Although toxoplasmosis is common in sea otters and can sometimes be fatal, this unusual strain appears to be capable of rapidly killing healthy adult otters. This rare strain of Toxoplasma hasn’t been detected on the California coast before, and may be a recent arrival, but scientists are concerned that if it contaminates the marine food chain it could potentially pose a public health risk.

“I have studied Toxoplasma infections in sea otters for 25 years — I have never ...

Sea otters killed by unusual parasite strain

2023-03-22

Four sea otters that stranded in California died from an unusually severe form of toxoplasmosis, according to a study from the California Department of Fish and Wildlife and the University of California, Davis. The disease is caused by the microscopic parasite Toxoplasma gondii. Scientists warn that this rare strain, never previously reported in aquatic animals, could pose a health threat to other marine wildlife and humans.

The preliminary findings, published in the journal Frontiers in Marine Science, note that toxoplasmosis is common in sea otters and can be fatal. This unusual strain appears to be especially virulent and capable of rapidly killing healthy adult otters.

The ...

Prevalence of statin use for primary prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease by race, ethnicity, 10-year disease risk

2023-03-22

About The Study: Statin use for primary prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) was low among all race and ethnicity groups regardless of ASCVD risk, with the lowest use occurring among Black and Hispanic adults in this study of survey data representing 39.4 million adults. Improvements in access to care may promote equitable use of primary prevention statins in Black and Hispanic adults.

Authors: Joshua A. Jacobs, Pharm.D., of the Spencer Fox Eccles University of Utah School of Medicine in Salt Lake City, and Ambarish Pandey, M.D., of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas, are the corresponding authors.

To ...