(Press-News.org)

New research published by investigators at Cedars-Sinai advances scientific understanding of how the brain weighs decisions involving what people like or value, such as choosing which book to read, which restaurant to pick for lunch—or even, which slot machine to play in a casino. Published today in the peer-reviewed journal Nature Human Behaviour, this study involved recording the activity of individual human neurons.

The study examined decisions called value-based choices, where there is not necessarily a right or wrong option, according to Ueli Rutishauser, PhD, senior author of the study, director of the Center for Neural Science and Medicine, and professor of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Biomedical Sciences at Cedars-Sinai.

“Learning how the brain makes these kinds of choices could help us better understand neurological disorders including addiction and obsessive-compulsive disorder,” Rutishauser said, “because all of these conditions can involve a person making the same choice over and over to their detriment.”

The 20 study participants, all volunteers, were patients with epilepsy who were hospitalized while doctors monitored their brain activity to determine the focal points of their seizures. This allowed investigators to record the activity of individual neurons within their brains while participants played a computer slot-machine game.

The game, called “two-armed bandit,” let participants choose one of two simulated slot machines in each round. Participants pushed a button to select their “bandit,” which then either paid out or did not. The bandits had unique markings, so participants could tell whether they had played each one before, and participants played several rounds over a 30-minute period.

Rutishauser explained the factors involved in making value-based choices:

Familiar options: “If participants had chosen a bandit several times before, they had a fairly good idea of how often it was a winner.”

Uncertain options: “For bandits they had only played a few times, participants were less certain of their prospect of a win.”

New options: “When a new bandit appeared for the first time, participants had to decide whether to choose a familiar bandit or risk choosing a new one. Sometimes it just feels good to do something new, and that has its own intrinsic value.”

Previous studies relied on functional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to monitor brain activity, and suggested that a brain region called the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) plays a primary role in weighing these factors. But in this recent study, Cedars-Sinai investigators determined that a completely different area, called the pre-supplementary motor area (pre-SMA), actually takes the lead.

Single-neuron recording allowed investigators to see that while the vmPFC signaled the “novelty” value of new bandits that appeared, it was the pre-SMA that calculated which option had the best chance of yielding the highest reward. And that signal was the basis on which participants made their choices.

“Previous studies weren't giving us a complete picture and couldn't draw the distinction we could here,” said Tomas Aquino, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow in the Rutishauser Lab and first author of the study. “Since our single-neuron recordings are more sensitive than other, more common methods, we could measure directly how preSMA neurons compute the value of each option and determine participants’ choices.”

Both the vmPFC and the pre-SMA are part of the brain’s frontal lobe, and both have been implicated in planning and decision-making activities, but in this study, for the first time, investigators were able to tease out their separate roles. This new discovery joins a number of other recent findings indicating that pre-SMA is critically important to human decision-making.

“The unique window into the human brain that is opened by these single-neuron recordings continues to deepen our understanding of the precise mechanisms behind cognitive processes,” said Adam Mamelak, MD, director of the Functional Neurosurgery Program at Cedars-Sinai and a co-author of the study. “These continued gains in understanding are the key to finding new treatments for complex neurological disorders and improving the lives of patients.”

This research is part of a long-standing collaboration between Cedars-Sinai and co-senior author John O’Doherty, Fletcher Jones Professor of Decision Neuroscience at the California Institute of Technology.

Funding: This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01DA040011, R01MH111425, R01MH110831, U01NS117839, and P50MH094258.

END

Microplastic pollution reduces energy production in a microscopic creature found in freshwater worldwide, new research shows.

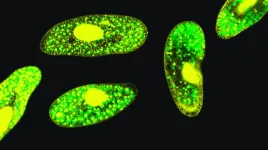

Paramecium bursaria contain algae that live inside their cells and provide energy by photosynthesis.

The new study, by the University of Exeter, tested whether severe microplastic contamination in the water affected this symbiotic relationship.

The results showed a 50% decline in net photosynthesis – a major impact on the algae’s ability to produce energy and release ...

SAN ANTONIO — March 23, 2023 —A study co-authored by Southwest Research Institute Senior Research Scientist Dr. Jason Hofgartner explains the unusual radar signatures of icy satellites orbiting Jupiter and Saturn. Their radar signatures, which differ significantly from those of rocky worlds and most ice on Earth, have long been a vexing question for the scientific community.

“Six different models have been published in an attempt to explain the radar signatures of the icy moons that orbit Jupiter and Saturn,” said Hofgartner, first author of the study, ...

Francis Crick Institute press release

Under strict embargo: 16:00 GMT 23 March 2023

Peer reviewed

Experimental study

Human stem cells

Researchers at the Francis Crick Institute have found that the body’s process of removing old and damaged cell parts, is also an essential part of tackling infections that take hold within our cells, like TB.

If this natural process can be harnessed with new treatments, it could present an alternative to, or improve use of antibiotics, especially where bacteria have become ...

The Francis Crick Institute press release

Under strict embargo: 16:00 GMT Thursday 23rd March

Peer reviewed

Experimental

Cells

Researchers at the Francis Crick Institute have uncovered a key role for a new type of cell in touch detection in the skin of the fruit fly.

Touch allows animals to navigate their environment by gathering information from the outside world. In their study published today in Nature Cell Biology, Dr Federica Mangione and Dr Nicolas Tapon shed light on how touch-sensitive organs assemble during development.

In particular the team studied the development ...

A protein complex prevents the repair of genome damage in human cells, in mice and in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans, a team of researchers at the University of Cologne has discovered. They also successfully inhibited this complex for the first time using a pharmaceutical agent.

“When we suppress the so-called DREAM complex in body cells, various repair mechanisms kick in, making these cells extremely resilient towards all kinds of DNA damage,” said Professor Dr Björn Schumacher, Director of the Institute for Genome Stability in Aging ...

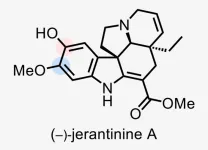

Plants produce all types of curious chemicals. Some deter predators. Some smell wonderful. Some even have medicinal value. One of these hidden gems is (–)-jerantinine A (JA), a molecule with remarkable anticancer properties, produced by a plant called Tabernaemontana corymbosa. Unfortunately, access to this Malaysian jungle plant and its promising chemical compound has been limited. Until now.

Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) chemists, led by Professor John E. Moses, have created a way to safely, quickly, and sustainably synthesize JA in the lab. To cancer biologists at CSHL, this breakthrough could mean future ...

Whether it’s diseases from bats, birds, pigs, or mosquitoes, climate change brings with it an increased risk of animal-borne (or “zoonotic”) diseases that can transmit to humans.

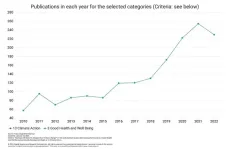

Digital Science, a technology company serving stakeholders across the research ecosystem, has today released its analysis of the global research response to climate change and zoonotic diseases, in the context of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) on climate and health.

Using data from Dimensions, Dr Briony Fane, Ann Campbell and Dr Juergen Wastl from Digital Science have explored published research, ...

Researchers have used pluripotent stem cells to make thymus organoids that support the development of patient-specific T-cells, researchers report March 23rd in the journal Stem Cell Reports. The proof-of-concept work provides the basis for studying human thymus function, T-cell development, and transplant immunity.

“We have established the framework for further basic science and translational research interrogating human thymus development and function in vitro, and in a patient-specific manner,” says senior author Holger Russ, of the University ...

When early Stone Age farmers first moved into Europe from the Near East about 8,000 years ago, they met and began mixing with the existing hunter-gatherer populations. Now genome-wide studies of hundreds of ancient genomes from this period show more hunter-gatherer ancestry in adaptive-immunity genes in the mixed population than would be expected by chance.

The findings, reported in Current Biology on March 23, suggest that mixing between the two groups resulted in mosaics of genetic variation that were acted upon by natural selection, a process through which all organisms, including humans, adapt and change ...

A male fly approaches a flower, lands on top of what he thinks is a female fly, and jiggles around. He’s trying to mate, but it isn’t quite working. He has another go. Eventually he gives up and buzzes off, unsuccessful. The plant, meanwhile, has got what it wanted: pollen.

A South African daisy, Gorteria diffusa, is the only daisy known to make such a complicated structure resembling a female fly on its petals. The mechanism behind this convincing three-dimensional deception, complete ...