(Press-News.org)

The saliva of mosquitoes infected with dengue viruses contains a substance that thwarts the human immune system and makes it easier for people to become infected with these potentially deadly viruses, new research reveals.

Dengue has spread in recent years to Europe and the Southern United States in addition to longstanding hotspots in tropical and subtropical areas such as Southeast Asia, Africa and Latin America. The new discovery, from a University of Virginia School of Medicine scientist and his collaborators, helps explain why the disease is so easily transmitted and could eventually lead to new ways to prevent infection.

“It is remarkable how clever these viruses are – they subvert mosquito biology to tamp down our immune responses so that infection can take hold,” said Mariano A. Garcia-Blanco, MD, PhD, who recently joined UVA as chair of the Department of Microbiology, Immunology and Cancer Biology. “There is no doubt in my mind that better understanding of the fundamental biology of transmission will eventually lead to effective transmission-blocking measures.”

Further, Garcia-Blanco suspects that researchers will find similar immune-dampening substances accompanying other mosquito-borne infections such as Zika, West Nile and yellow fever. “Our findings are almost certainly going to be applicable to infections with other flaviviruses,” Garcia-Blanco said. “The specific molecules here are unlikely to apply to malaria, but the concept is generalizable to viral infections.”

Understanding Dengue

Approximately half the world’s population is at risk for dengue, and roughly 400 million people are infected every year. Dengue’s symptoms, including fever, nausea and skin rash, are often mistaken for other diseases. Most people will have mild cases, but about 1 in 20 will develop severe illness that can lead to shock, internal bleeding and death. Unfortunately, it’s possible to contract dengue repeatedly, as it is caused by four related viruses transmitted primarily by the Aedes aegypti species of mosquito. There is no treatment, but the new discovery from Garcia-Blanco and his colleagues identifies an important contributor to the disease’s spread as researchers seek to find better ways to combat it.

Garcia-Blanco and his team found that infected mosquitoes’ saliva contained not just the expected dengue virus but a powerful conspirator: molecules produced by the virus that can blunt the body’s immune response. The injection of these molecules, called sfRNAs, during the mosquito bite makes it more likely that the victim will become infected with dengue, the scientists conclude.

“By introducing this RNA at the biting site, dengue-infected saliva prepares the terrain for an efficient infection and gives the virus an advantage in the first battle between it and our immune defenses,” the researchers write in a new scientific paper outlining their findings.

Scientists who study mosquitoes previously had suspected that the insects’ saliva might contain some type of payload to enhance the potential for infection. Garcia-Blanco’s team’s new findings pinpoints one weapon in the viruses’ arsenal and opens the door to finding new ways to help reduce transmission and control the disease’s spread. For now, the best way to avoid getting seriously sick with dengue remains to avoid getting bitten.

“It’s incredible that the virus can hijack these molecules so that their co-delivery at the mosquito bite site gives it an advantage in establishing an infection,” said researcher Tania Strilets, a graduate student with Garcia-Blanco and co-first author of the scientific paper. “These findings provide new perspectives on how we can counteract dengue virus infections from the very first bite of the mosquito.”

Findings Published

The researchers have published their findings in the scientific journal PLOS Pathogens. The team consisted of Shih-Chia Yeh, Strilets, Wei-Lian Tan, David Castillo, Hacène Medkour, Félix Rey-Cadilhac, Idalba M. Serrato-Pomar, Florian Rachenne, Avisha Chowdhury, Vanessa Chuo, Sasha R. Azar, Moirangthem Kiran Singh, Rodolphe Hamel, Dorothée Missé, R. Manjunatha Kini, Linda J. Kenney, Nikos Vasilakis, Marc A. Marti-Renom, Guy Nir, Julien Pompon and Garcia-Blanco. Most of Garcia-Blanco’s work on the project was conducted while he was at Duke-NUS Medical School and the University of Texas Medical Branch.

The researchers reported no financial interest in the work.

Garcia-Blanco’s research for the project was supported by the Duke-NUS Signature Research Programme in Emerging Infectious Diseases funded by the Agency for Science Technology and Research (A*Star Singapore) and by the National Institutes of Health’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, grant AID P01 AI150585.

To keep up with the latest medical research news from UVA, subscribe to the Making of Medicine blog at http://makingofmedicine.virginia.edu.

END

Humans have complex social behavior, diverse communication skills, and a capacity for highly developed tool use. Researchers argue that human evolution may resemble the process of animal domestication, where less aggressive animals are favoured. In the same way, human evolution may be the result of natural selection for more prosocial and cooperative individuals. Such individuals are more likely to interact with others and form complex communities, in which they can learn from each other.

“The theory of self-domestication is hard to test”, says first author Limor Raviv. “This is because only one other species besides humans has been argued ...

OAK BROOK, Ill. – Researchers who surveyed women attending breast cancer screening appointments found that one in five is likely to skip additional testing after an abnormal finding on their mammogram if there is a deductible or co-payment, according to an editorial published in Radiology, a journal of the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA).

Health care costs and insurance premiums have increased in recent years. With the advent of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), high-deductible health plans (HDHPs) have grown ...

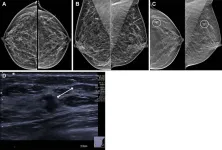

OAK BROOK, Ill. – Ultrasound is an effective standalone diagnostic method in patients with focal breast complaints, according to a study published in Radiology, a journal of the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA). Focal breast complaints can refer to pain, lumps, nipple discharge or other symptoms and conditions confined to a specific area of the breast.

In women, focal breast complaints are a frequent problem. In the Netherlands, approximately 70,000 women visit radiology departments annually with focal breast complaints. The most common being the presence of lumps or pain. Many women who have focal breast complaints are between the ages of 30 and 50 years.

Digital breast ...

BALTIMORE, April, 4, 2023-- As more consumers turn to the newly available ChatGPT for health advice, researchers are eager to see whether the information provided by the artificial intelligence chatbot is reliable and accurate. A new study conducted by researchers at the University of Maryland School of Medicine (UMSOM) indicates that the answers generated provide correct information the vast majority of the time; sometimes, though, the information is inaccurate or even fictitious.

Findings were published today in the journal Radiology.

In February 2023, UMSOM researchers created a set of 25 questions related to advice on getting screened ...

A recent study in the Journal of Biological Chemistry revealed the key to a protein that commonly causes blindness. The biological process involves a protein that is essential for transporting toxic compounds out of the eye, similar to a garbage recycling service. The challenge is that, like food and the waste it generates, these compounds are essential for the eye to function properly — until they build up and cause blindness.

The scientists behind the study research a protein transporter, called ABCA4, that lines the edges of specialized photoreceptor cells in the retina and is normally poised to remove toxic, fatty retinal byproducts ...

In a study conducted in the lab as well as during the COVID-19 lockdowns, participants reported higher levels of tiredness after eight hours of social isolation. The results suggest that low energy may be a basic human response to a lack of social contact. The study conducted at the University of Vienna and published in Psychological Science also showed that this response was affected by social personality traits of the participants.

If we do not eat for an extended period, a series of biological processes ensue that create a craving sensation we recognize as hunger. As a social species, we also need other people to survive. Evidence shows that a lack of social contact induces ...

Insilico Medicine (“Insilico”), a clinical-stage generative artificial intelligence (AI)-driven drug discovery company, today announced that four abstracts have been accepted as poster presentations at the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) Annual Meeting 2023.

Insilico will present four novel inhibitors for the treatment of cancer developed with its end-to-end Pharma.AI platform. Drawing from trillions of data points and millions of compounds and molecular fragments, the platform uses ...

Red tides, caused by Karenia brevis blooms, are a recurring problem in the coastal Gulf of Mexico. The organism, Karenia brevis, produces toxins that can cause fish kills, respiratory irritation in humans and cause death in sea turtles, dolphins, manatees and birds.

The ability to detect red tide blooms at all life stages and cell concentrations is critical to increasing predictive capabilities and developing potential mitigation strategies to protect public health and vital resources.

Current methods used to monitor red tide such as microscopic identification and enumeration, standard flow cytometry, as well as others have limitations. Some of these ...

April 4, 2023, TORONTO — Becoming the first genomics lab to be accredited by three of the leading North American accreditation organizations positions OICR Genomics to generate new discoveries about what drives diseases like cancer and new, personalized ways to diagnose and treat them.

The lab earned a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) certificate of accreditation in January 2023 for its whole genome and whole transcriptome sequencing assay, a comprehensive genetic test that can find all changes in the DNA of a tumour. This comes after accreditation from the College of American Pathologists (CAP) in 2021 and from Accreditation Canada Diagnostics (ACD) — ...

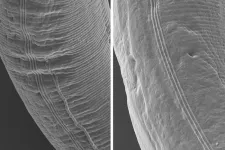

SPOKANE, Wash.—Researchers have long known that many animals live longer in colder climates than in warmer climates. New research in C. elegans nematode worms suggests that this phenomenon is tied to a protein found in the nervous system that controls the expression of collagens, the primary building block of skin, bone and connective tissue in many animals.

Since the C. elegans’ protein is similar to nervous system receptor proteins found in other species including humans, the discovery potentially brings scientists closer to finding ways to harness collagen expression to slow down human aging and increase lifespan in the ...