(Press-News.org) Captain of her high school tennis team and a four-year veteran of varsity tennis in college, Amanda Studnicki had been training for this moment for years.

All she had to do now was think small. Like ping pong small.

For weeks, Studnicki, a graduate student at the University of Florida, served and rallied against dozens of players on a table tennis court. Her opponents sported a science-fiction visage, a cap of electrodes streaming off their heads into a backpack as they played against either Studnicki or a ball-serving machine. That cyborg look was vital to Studnicki’s goal: to understand how our brains react to the intense demands of a high-speed sport like table tennis – and what difference a machine opponent makes.

Studnicki and her advisor, Daniel Ferris, discovered that the brains of table tennis players react very differently to human or machine opponents. Faced with the inscrutability of a ball machine, players’ brains scrambled themselves in anticipation of the next serve. While with the obvious cues that a human opponent was about to serve, their neurons hummed in unison, seemingly confident of their next move.

The findings have implications for sports training, suggesting that human opponents provide a realism that can’t be replaced with machine helpers. And as robots grow more common and sophisticated, understanding our brains’ response could help make our artificial companions more naturalistic.

“Robots are getting more ubiquitous. You have companies like Boston Dynamics that are building robots that can interact with humans and other companies that are building socially assistive robots that help the elderly,” said Ferris, a professor of biomedical engineering at UF. “Humans interacting with robots is going to be different than when they interact with other humans. Our long term goal is to try to understand how the brain reacts to these differences.”

Ferris’s lab has long studied the brain’s response to visual cues and motor tasks, like walking and running. He was looking to upgrade to studying complex, fast-paced action when Studnicki, with her tennis background, joined the research group. So the lab decided tennis was the perfect sport to address these questions with. But the oversized movements – especially high overhand serves – proved an obstacle to the burgeoning tech.

“So we literally scaled things down to table tennis and asked all the same questions we had for tennis before,” Ferris said. The researchers still had to compensate for the smaller movements of table tennis. So Ferris and Studnicki doubled the 120 electrodes in a typical brain-scanning cap, each bonus electrode providing a control for the rapid head movements during a table tennis match.

With all these electrodes scanning the brain activity of players, Studnicki and Ferris were able to tune into the brain region that turns sensory information into movement. This area is known as the parieto-occipital cortex.

“It takes all your senses – visual, vestibular, auditory – and it gives information on creating your motor plan. It’s been studied a lot for simple tasks, like reaching and grasping, but all of them are stationary,” Studnicki said. “We wanted to understand how it worked for complex movements like tracking a ball in space and intercepting it, and table tennis was perfect for this.”

The researchers analyzed dozens of hours of play against both Studnicki and the ball machine. When playing against another human, players’ neurons worked in unison, like they were all speaking the same language. In contrast, when players faced a ball-serving machine, the neurons in their brains were not aligned with one another. In the neuroscience world, this lack of alignment is known as desynchronization.

“If we have 100,000 people in a football stadium and they’re all cheering together, that’s like synchronization in the brain, which is a sign the brain is relaxed" Ferris said. “If we have those same 100,000 people but they’re all talking to their friends, they’re busy but they’re not in sync. In a lot of cases, that desynchronization is an indication that the brain is doing a lot of calculations as opposed to sitting and idling.”

The team suspects that the players’ brains were so active while waiting for robotic serves because the machine provides no cues of what they are going to do next. What’s clear is that our brains process these two experiences very differently, which suggests that training with a machine might not offer the same experience as playing against a real opponent.

“I still see a lot of value in practicing with a machine,” Studnicki said. “But I think machines are going to evolve in the next 10 or 20 years, and we could see more naturalistic behaviors for players to practice against.”

END

Table tennis brain teaser: Playing against robots makes our brains work harder

Brain scans taken during table tennis reveal differences in how we respond to human versus machine opponents

2023-04-10

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

For chatbots and beyond: Improving lives with data starts with improving machine learning

2023-04-10

You’d be hard pressed to find an industry today that doesn’t use data in some capacity. Whether it's health care workers using data to report the rate of flu infections in a certain state, manufacturers using data to better understand average production times, or even a small coffee shop owner flipping through sales data to learn about the previous month’s bestselling latte, data can reveal patterns and offer insights into our everyday behavior.

All of this data plays a critical role in artificial intelligence ...

Mild COVID during pregnancy does not slow brain development in babies, study finds

2023-04-10

NEW YORK, NY (April 10, 2023)--Columbia researchers have found that babies born to moms who had mild or asymptomatic COVID during pregnancy are normal, based on results from a comprehensive assessment of brain development.

The findings expand on a smaller study that used maternal reports to assess the development of babies born in New York City during the first wave of the pandemic. That study found no differences in brain development between babies who were exposed to COVID in utero and those who were not exposed.

For the new study, the researchers developed a method of observing infants remotely, ...

Kids judge Alexa smarter than Roomba, but say both deserve kindness

2023-04-10

DURHAM, N.C. –- Most kids know it’s wrong to yell or hit someone, even if they don’t always keep their hands to themselves. But what about if that someone’s name is Alexa?

A new study from Duke developmental psychologists asked kids just that, as well as how smart and sensitive they thought the smart speaker Alexa was compared to its floor-dwelling cousin Roomba, an autonomous vacuum.

Four- to eleven-year-olds judged Alexa to have more human-like thoughts and emotions than Roomba. But despite the perceived difference in intelligence, kids felt neither the Roomba nor the Alexa deserve to be yelled at or harmed. That feeling dwindled as kids advanced ...

Hooper creating public database of slaving voyages across the Indian Ocean and Asia

2023-04-10

Jane Hooper, Associate Professor, History, received funding for the project: "Global Passages: Creating a Public Database of Slaving Voyages across the Indian Ocean and Asia."

Hooper, along with three other scholars, has received a three-year digital production grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities to support a major expansion of the open access SlaveVoyages website, available online at https://www.slavevoyages.org. The primary investigators will create an Indian Ocean and Asia (IOA) database of voyages that ...

A new technique opens the door to safer gene editing by reducing the mutation problem in gene therapy

2023-04-10

CRISPR-Cas9 is widely used to edit the genome by studying genes of interest and modifying disease-associated genes. However, this process is associated with side effects including unwanted mutations and toxicity. Therefore, a new technology that reduces these side effects is needed to improve its usefulness in industry and medicine. Now, researchers at Kyushu University in southern Japan and Nagoya University School of Medicine in central Japan have developed an optimized genome-editing method that vastly reduces mutations, opening the door to more effective treatment of genetic diseases with fewer unwanted mutations. Their findings were published in Nature Biomedical Engineering.

Genome-editing ...

Medicaid ‘cliff’ adds to racial and ethnic disparities in care for near-poor seniors

2023-04-10

PITTSBURGH, April 10, 2023 – Black and Hispanic older adults whose annual income is slightly above the federal poverty level are more likely than their white peers to face cost-related barriers to accessing health care and filling medications for chronic conditions, according to new research led by a University of Pittsburgh School of Public Health scientist.

Published today in JAMA Internal Medicine, the analysis links these disparities to a Medicaid “cliff” – an abrupt end ...

Potential drug treats fatty liver disease in animal models, brings hope for first human treatment

2023-04-10

A recently developed amino acid compound successfully treats nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in non-human primates — bringing scientists one step closer to the first human treatment for the condition that is rapidly increasing around the world, a study suggests.

Researchers at Michigan Medicine developed DT-109, a glycine-based tripeptide, to treat the severe form of fatty liver disease called nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. More commonly known as NASH, the disease causes scarring and inflammation in the liver and is estimated to affect up to 6.5% of the global population.

Results ...

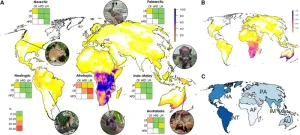

Scientists show how we can anticipate rather than react to extinction in mammals

2023-04-10

Most conservation efforts are reactive. Typically, a species must reach threatened status before action is taken to prevent extinction, such as establishing protected areas. A new study published in the journal Current Biology on April 10 shows that we can use existing conservation data to predict which currently unthreatened species could become threatened and take proactive action to prevent their decline before it is too late.

“Conservation funding is really limited,” says lead author Marcel Cardillo (@MarcelCardillo) of Australian National University. “Ideally, what we need is some way of anticipating species that may not be threatened ...

This elephant’s self-taught banana peeling offers glimpse of elephants’ broader abilities

2023-04-10

Elephants like to eat bananas, but they don’t usually peel them first in the way humans do. A new report in the journal Current Biology on April 10, however, shows that one very special Asian elephant named Pang Pha picked up banana peeling all on her own while living at the Berlin Zoo. She reserves it for yellow-brown bananas, first breaking the banana before shaking out and collecting the pulp, leaving the thick peel behind.

The female elephant most likely learned the unusual peeling behavior ...

Health care access, affordability among adults with self-reported post–COVID-19 condition

2023-04-10

About The Study: In this survey study of 9,400 adults ages 18 to 64, a higher rate of respondents with self-reported post–COVID-19 condition (PCC; also known as long COVID) did not obtain needed health care in the past year because of cost compared with adults without PCC. Adults with PCC were also more likely to have unmet needs because of difficulties getting timely appointments or health plan authorization, among other challenges with health care institutions or health insurance. These findings suggest that improved health care access for adults with PCC may require developing clinical protocols and addressing insurance-related barriers.

Authors: Michael ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Emerging class of antibiotics to tackle global tuberculosis crisis

Researchers create distortion-resistant energy materials to improve lithium-ion batteries

Scientists create the most detailed molecular map to date of the developing Down syndrome brain

Nutrient uptake gets to the root of roots

Aspirin not a quick fix for preventing bowel cancer

HPV vaccination provides “sustained protection” against cervical cancer

Many post-authorization studies fail to comply with public disclosure rules

GLP-1 drugs combined with healthy lifestyle habits linked with reduced cardiovascular risk among diabetes patients

Solved: New analysis of Apollo Moon samples finally settles debate about lunar magnetic field

University of Birmingham to host national computing center

Play nicely: Children who are not friends connect better through play when given a goal

Surviving the extreme temperatures of the climate crisis calls for a revolution in home and building design

The wild can be ‘death trap’ for rescued animals

New research: Nighttime road traffic noise stresses the heart and blood vessels

Meningococcal B vaccination does not reduce gonorrhoea, trial results show

AAO-HNSF awarded grant to advance age-friendly care in otolaryngology through national initiative

Eight years running: Newsweek names Mayo Clinic ‘World’s Best Hospital’

Coffee waste turned into clean air solution: researchers develop sustainable catalyst to remove toxic hydrogen sulfide

Scientists uncover how engineered biochar and microbes work together to boost plant-based cleanup of cadmium-polluted soils

Engineered biochar could unlock more effective and scalable solutions for soil and water pollution

Differing immune responses in infants may explain increased severity of RSV over SARS-CoV-2

The invisible hand of climate change: How extreme heat dictates who is born

Surprising culprit leads to chronic rejection of transplanted lungs, hearts

Study explains how ketogenic diets prevent seizures

New approach to qualifying nuclear reactor components rolling out this year

U.S. medical care is improving, but cost and health differ depending on disease

AI challenges lithography and provides solutions

Can AI make society less selfish?

UC Irvine researchers expose critical security vulnerability in autonomous drones

Changes in smoking status and their associations with risk of Parkinson’s, death

[Press-News.org] Table tennis brain teaser: Playing against robots makes our brains work harderBrain scans taken during table tennis reveal differences in how we respond to human versus machine opponents