(Press-News.org) Researchers have designed a low-cost, energy-efficient robotic hand that can grasp a range of objects – and not drop them – using just the movement of its wrist and the feeling in its ‘skin’.

Grasping objects of different sizes, shapes and textures is a problem that is easy for a human, but challenging for a robot. Researchers from the University of Cambridge designed a soft, 3D printed robotic hand that cannot independently move its fingers but can still carry out a range of complex movements.

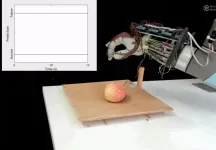

The robot hand was trained to grasp different objects and was able to predict whether it would drop them by using the information provided from sensors placed on its ‘skin’.

This type of passive movement makes the robot far easier to control and far more energy-efficient than robots with fully motorised fingers. The researchers say their adaptable design could be used in the development of low-cost robotics that are capable of more natural movement and can learn to grasp a wide range of objects. The results are reported in the journal Advanced Intelligent Systems.

In the natural world, movement results from the interplay between the brain and the body: this enables people and animals to move in complex ways without expending unnecessary amounts of energy. Over the past several years, soft components have begun to be integrated into robotics design thanks to advances in 3D printing techniques, which have allowed researchers to add complexity to simple, energy-efficient systems.

The human hand is highly complex, and recreating all of its dexterity and adaptability in a robot is a massive research challenge. Most of today’s advanced robots are not capable of manipulation tasks that small children can perform with ease. For example, humans instinctively know how much force to use when picking up an egg, but for a robot this is a challenge: too much force, and the egg could shatter; too little, and the robot could drop it. In addition, a fully actuated robot hand, with motors for each joint in each finger, requires a significant amount of energy.

In Professor Fumiya Iida’s Bio-Inspired Robotics Laboratory in Cambridge’s Department of Engineering, researchers have been developing potential solutions to both problems: a robot hand than can grasp a variety of objects with the correct amount of pressure while using a minimal amount of energy.

“In earlier experiments, our lab has shown that it’s possible to get a significant range of motion in a robot hand just by moving the wrist,” said co-author Dr Thomas George-Thuruthel, who is now based at University College London (UCL) East. “We wanted to see whether a robot hand based on passive movement could not only grasp objects, but would be able to predict whether it was going to drop the objects or not, and adapt accordingly.”

The researchers used a 3D-printed anthropomorphic hand implanted with tactile sensors, so that the hand could sense what it was touching. The hand was only capable of passive, wrist-based movement.

The team carried out more than 1200 tests with the robot hand, observing its ability to grasp small objects without dropping them. The robot was initially trained using small 3D printed plastic balls, and grasped them using a pre-defined action obtained through human demonstrations.

“This kind of hand has a bit of springiness to it: it can pick things up by itself without any actuation of the fingers,” said first author Dr Kieran Gilday, who is now based at EPFL in Lausanne, Switzerland. “The tactile sensors give the robot a sense of how well the grip is going, so it knows when it’s starting to slip. This helps it to predict when things will fail.”

The robot used trial and error to learn what kind of grip would be successful. After finishing the training with the balls, it then attempted to grasp different objects including a peach, a computer mouse and a roll of bubble wrap. In these tests, the hand was able to successfully grasp 11 of 14 objects.

“The sensors, which are sort of like the robot’s skin, measure the pressure being applied to the object,” said George-Thuruthel. “We can’t say exactly what information the robot is getting, but it can theoretically estimate where the object has been grasped and with how much force.”

“The robot learns that a combination of a particular motion and a particular set of sensor data will lead to failure, which makes it a customisable solution,” said Gilday. “The hand is very simple, but it can pick up a lot of objects with the same strategy.”

“The big advantage of this design is the range of motion we can get without using any actuators,” said Iida. “We want to simplify the hand as much as possible. We can get lots of good information and a high degree of control without any actuators, so that when we do add them, we’ll get more complex behaviour in a more efficient package.”

A fully actuated robotic hand, in addition to the amount of energy it requires, is also a complex control problem. The passive design of the Cambridge-designed hand, using a small number of sensors, is easier to control, provides a wide range of motion, and streamlines the learning process.

In future, the system could be expanded in several ways, such as by adding computer vision capabilities, or teaching the robot to exploit its environment, which would enable it to grasp a wider range of objects.

This work was funded by UK Research and Innovation (UKRI), and Arm Ltd. Fumiya Iida is a Fellow of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge.

END

It’s all in the wrist: energy-efficient robot hand learns how not to drop the ball

2023-04-12

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

How an African bird might inspire a better water bottle

2023-04-12

An extreme closeup of feathers from a bird with an uncanny ability to hold water while it flies could inspire the next generation of absorbent materials.

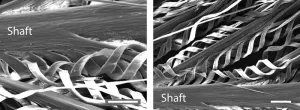

With high resolution microscopes and 3D technology, researchers at Johns Hopkins University and Massachusetts Institute of Technology captured an unprecedented view of feathers from the desert-dwelling sandgrouse, showcasing the singular architecture of their feathers and revealing for the first time how they can hold so much water.

“It’s super fascinating to see how nature managed to create structures so perfectly efficient to take ...

Time-restricted fasting could cause fertility problems

2023-04-12

Time-restricted fasting diets could cause fertility problems according to new research from the University of East Anglia.

A new study published today shows that time-restricted fasting affects reproduction differently in male and female zebrafish.

Importantly, some of the negative effects on eggs and sperm quality can be seen after the fish returned to their normal levels of food consumption.

The research team say that while the study was conducted in fish, their findings highlight the importance of considering not just the effect of fasting on weight and health, but also on fertility.

Prof Alexei Maklakov, from UEA’s School of Biological Sciences, said: “Time-restricted ...

Scientists uncover the amazing way sandgrouse hold water in their feathers

2023-04-12

Many birds’ feathers are remarkably efficient at shedding water — so much so that “like water off a duck’s back” is a common expression. Much more unusual are the belly feathers of the sandgrouse, especially Namaqua sandgrouse, which absorb and retain water so efficiently the male birds can fly more than 20 kilometers from a distant watering hole back to the nest and still retain enough water in their feathers for the chicks to drink and sustain themselves in the searing deserts ...

Alternative route used by specialized immune cells to colonize the embryonic brain suggests new approach to fighting fetal brain dysfunction

2023-04-12

A team from the Nagoya University Graduate School of Medicine in Japan has uncovered new information about how microglia, the resident immune cells in the brain, colonize the brain during the embryonic stage of development. Although erythromyeloid progenitors (EMPs) were previously thought to divide into either microglia or macrophages, the group found that macrophages that enter the brain primordium —the brain in its earliest recognizable stage of development— can become microglia at later stages of development. These findings demonstrate the plasticity of these ...

The brain’s cannabinoid system protects against addiction following childhood maltreatment

2023-04-12

High levels of the body’s own cannabinoid substances protect against developing addiction in individuals previously exposed to childhood maltreatment, according to a new study from Linköping University in Sweden. The brains of those who had not developed an addiction following childhood maltreatment seem to process emotion-related social signals better.

Childhood maltreatment has long been suspected to increase the risk of developing a drug or alcohol addiction later in life. Researchers at Linköping University have previously shown that this risk is three times higher if you have been exposed to childhood maltreatment ...

Pregnant women show robust and variable immunity during COVID-19

2023-04-12

New research from the Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity (Doherty Institute) has found that pregnant women display a strong immune response to SARS-CoV-2 infection, comparable to that of non-pregnant women.

Published in JCI Insight, the study looked at the immune responses to SARS-CoV-2 in unvaccinated pregnant and non-pregnant women and found similar levels of antibodies and T and B cell responses, responsible for long-term protection.

Lead author of the paper, University of ...

Antimicrobial stewardship programs essential for preventing C. difficile in hospitals

2023-04-12

ARLINGTON, Va. (April 12, 2023) — Five medical organizations say it is essential that hospitals establish antimicrobial stewardship programs to prevent Clostridioides difficile (C. difficile) infections. These infections, linked to antibiotic use, cause difficult-to-treat diarrhea, longer hospital stays, and higher costs. C. difficile infections are fatal for more than 12,000 people in the United States each year.

Strategies to Prevent Clostridioides difficile Infections in Acute Care Hospitals: 2022 Update, gives evidence-based, ...

Mitochondria power-supply failure may cause age-related cognitive impairment

2023-04-12

LA JOLLA—(April 12, 2023) Brains are like puzzles, requiring many nested and codependent pieces to function well. The brain is divided into areas, each containing many millions of neurons connected across thousands of synapses. These synapses, which enable communication between neurons, depend on even smaller structures: message-sending boutons (swollen bulbs at the branch-like tips of neurons), message-receiving dendrites (complementary branch-like structures for receiving bouton messages), and power-generating mitochondria. To create a cohesive brain, all these pieces must be accounted for.

However, in the aging brain, these ...

Education and peer support cut binge-drinking by National Guard members in half, study shows

2023-04-12

A new study shows promise for reducing risky drinking among Army National Guard members over the long term, potentially improving their health and readiness to serve.

The number of days each month that Guard members said they had been binge-drinking dropped by up to half, according to the new findings by a University of Michigan team published in the journal Addiction.

The drop happened over the course of a year among Guard members who did multiple brief online education sessions designed for members of the military, and among those who did an initial online education session followed by supportive ...

World’s biggest cumulative logjam, newly mapped in the Arctic, stores 3.4 million tons of carbon

2023-04-11

WASHINGTON — Throughout the Arctic, fallen trees make their way from forests to the ocean by way of rivers. Those logs can stack up as the river twists and turns, resulting in long-term carbon storage. A new study has mapped the largest known woody deposit, covering 51 square kilometers (20 square miles) of the Mackenzie River Delta in Nunavut, Canada, and calculated that the logs store about 3.4 million tons (about 3.1 million metric tons) of carbon.

“To put that in perspective, that’s about two and a half million ...