(Press-News.org)

Researchers from the University of Michigan have found that an extra copy of a gene in Down syndrome patients causes improper development of neurons in mice.

The gene in question, called Down syndrome cell adhesion molecule, or DSCAM, is also implicated in other human neurological conditions, including autism spectrum disorders, bipolar disorder and intractable epilepsy.

The cause of Down syndrome is known to be an extra copy of chromosome 21, or trisomy 21. But because this chromosome contains more than 200 genes—including DSCAM—a major challenge in Down syndrome research and treatments is determining which gene or genes on the chromosome contribute to which specific symptoms of the syndrome.

"The ideal path for treatment would be to identify the gene that causes a medical condition, and then target this gene or other genes that it works with to treat that aspect of Down syndrome," said Bing Ye, a neuroscientist at the U-M Life Sciences Institute and lead author of the study.

"But for Down syndrome, we can't just sequence patient genomes to find such genes, because we'd find at least 200 different genes that are changed. We have to dig deeper to figure out which of those genes causes which problem."

For this work, researchers turn to animal models of Down syndrome. By studying mice that have a third copy of the mouse equivalent of chromosome 21, Ye and his team have now demonstrated how an extra copy of DSCAM contributes to neuronal dysfunction. Their findings are described in an April 20 study in PLOS Biology.

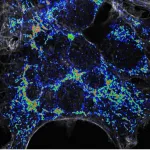

Each neuron has two sets of branches that extend out from the cell center: dendrites, which receive signals from other nerve cells, and axons, which send signals to other neurons. Ye and colleagues previously determined that overabundance of the protein encoded by DSCAM can cause overgrowth of axons in fruit fly neurons.

Guided by their research in flies, the team has now found that a third copy of DSCAM in mice leads to increased axon growth and neuronal connections (called synapses) in the types of neurons that put the brakes on other neurons' activities. These changes lead to greater inhibition of other neurons in the cerebral cortex—a part of the brain that is involved in sensation, cognition and behavior.

"It's known that these inhibitory synapses are changed in Down syndrome mouse models, but the gene that underlies this change is unknown," said Ye, who is also a professor of cell and developmental biology at the U-M Medical School. "We show here that the extra copy of DSCAM is the primary cause of the excessive inhibitory synapses in the cerebral cortex."

The team demonstrated that in mice that had only two copies of DSCAM, but three copies of the other genes that are similar to human chromosome 21 genes, axon growth appeared normal.

"These results are striking because, although these mice have an extra copy of about a hundred genes, normalization of this single gene, DSCAM, rescues normal inhibitory synaptic function," said Paul Jenkins, assistant professor of pharmacology and psychiatry at the Medical School and co-corresponding author of the study.

"This suggests that modulation of DSCAM expression levels could be a viable therapeutic strategy for repairing synaptic deficits seen in Down syndrome. In addition, given that alterations of DSCAM levels are associated with other brain disorders like autism spectrum disorder and bipolar disorder, these results shed insight into potential mechanisms underlying other human diseases."

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the Brain Research Foundation and the University of Michigan. All procedures performed in mice were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Michigan and performed in accordance with institutional guidelines.

Study authors are Hao Liu, René Caballero-Florán, Ty Hergenreder, Tao Yang, Jacob Hull, Geng Pan, Ruonan Li, Macy W. Veling, Lori Isom, Kenneth Kwan, Paul Jenkins, and Bing Ye of U-M; Z. Josh Huang of Duke University; and Peter Fuerst of the University of Idaho.

Study (available when embargo lifts): DSCAM gene triplication causes excessive 1 GABAergic synapses in the neocortex 2 in Down syndrome mouse models (DOI: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3002078)

END

A gene involved in Down syndrome puts the brakes on neurons' activity in mice, new study shows

2023-04-20

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Cracking the case of mitochondrial repair and replacement in metabolic stress

2023-04-20

LA JOLLA (April 20, 2023)—Scientists often act as detectives, piecing together clues that alone may seem meaningless but together crack the case. Professor Reuben Shaw has spent nearly two decades piecing together such clues to understand the cellular response to metabolic stress, which occurs when cellular energy levels dip. Whether energy levels fall because the cell’s powerhouses (mitochondria) are failing or due to a lack of necessary energy-making supplies, the response is the same: get rid of the damaged mitochondria and create new ones.

Now, in a study published in Science on April 20, 2023, Shaw and team cracked ...

The climate crisis and biodiversity crisis can’t be approached as two separate things

2023-04-20

Human beings have massively changed the Earth system. Greenhouse-gas emissions produced by human activities have caused the global mean temperature to rise by more than 1.1 degrees Celsius compared to the preindustrial era. And every year, there are additional emissions of carbon dioxide, methane and other greenhouse gases, currently amounting to more than 55 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent. This unprecedented climate crisis has consequences for the entire planet – the distribution of precipitation ...

Economic growth alone is not enough to eliminate rabies

2023-04-20

Economic growth alone may not be enough to deliver the internationally agreed target to end human deaths from dog mediated rabies, according to new research from the University of Surrey. The study identifies that targeting vulnerable populations and improving responsible pet ownership are urgently needed to eradicate the deadly disease, which has strong associations with poverty.

In a landmark study, Surrey researchers investigated whether incidences of rabies are an inevitable consequence of poverty or whether other measures of development, such as healthcare access, can play a role in tackling this preventable disease.

Dr ...

PLOS Genetics to launch Microbial Section

2023-04-20

SAN FRANCISCO — PLOS today announced that PLOS Genetics is expanding the scope of its journal with a renamed section called Microbial Genetics. This section will replace the former Prokaryotic Genetics section to emphasize research on microbes more broadly with the aim to publish studies that use genetic approaches to provide insights into how bacteria as well as archaea and their phages/viruses, fungi (including yeasts and filamentous fungi), and protists function and interact with the biotic and abiotic world.

PLOS Genetics has an established presence in the fungal genetics community, but this ...

Moffitt researchers discover pathway critical for lymphoma development

2023-04-20

TAMPA, Fla. — MYC proteins are important regulators of cancer cell growth, proliferation and metabolism through their ability to increase the expression of proteins involved in these processes. Deregulation of MYC proteins occurs in more than half of all cancers and is associated with poor patient prognosis and outcomes. Numerous researchers have devoted significant efforts to try to target MYC proteins as a therapeutic approach to treat cancer. However, this has been extremely challenging to date, and other complementary strategies are being investigated.

In a new article in Blood Cancer Discovery, which was published simultaneously with a presentation ...

Water arsenic including in public water is linked to higher urinary arsenic totals among the U.S. population

2023-04-20

April 20, 2023-- A new study by researchers at Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health shows that water arsenic levels are linked to higher urinary arsenic among the U.S. population for users of both private wells and public water systems. The findings are published in the journal Environmental Research.

Long-term exposure to arsenic even at low and moderate levels can increase the risk of cancer and other types of chronic disease. While drinking water along with diet is a major source ...

UHN Researchers publish ground breaking clinical trial in lung transplantation

2023-04-20

(Toronto, April 20, 2023) Storing donor lungs for transplant at 10 degrees Celsius markedly increases the length of time the organ can live outside the body according to research led by a team of scientists at the Toronto Lung Transplant Program in the Ajmera Transplant Centre at the University Health Network (UHN).

The prospective multicenter, nonrandomized clinical trial study of 70 patients demonstrated that donor lungs remained healthy and viable for transplant up to four times longer compared ...

Turkey’s next quake: USC research shows where, how bad — but not ‘when’

2023-04-20

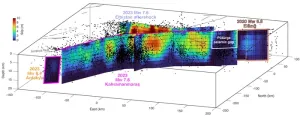

Researchers know a lot about Turkey’s next major earthquake. They can pinpoint the probable epicenter, estimate its strength and see the spatial footprint of where damage is most likely to occur.

They just can’t say when it will happen.

That’s the main takeaway from a new USC-led study that appears today (April 20) in Seismica.

Using remote sensing, USC geophysicist Sylvain Barbot and his fellow researchers documented the massive Feb. 6 quake that killed more than 50,000 people in Eastern Turkey and toppled more than 100,000 buildings.

Alarmingly, researchers found that a section of the fault remains unbroken and locked – a sign that the plates there ...

Astrocyte dysfunction causes cognitive decline

2023-04-20

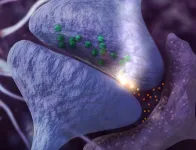

People with dementia have protein build-up in astrocytes that may trigger abnormal antiviral activity and memory loss, according to a preclinical study by a team of Weill Cornell Medicine investigators.

Dysfunction in cells called neurons, which transmit messages throughout the brain, has long been the prime suspect in dementia-related cognitive deficits. But a new study, published in Science Advances on April 19, suggests that abnormal immune activity in non-neuronal brain cells called astrocytes is sufficient to cause cognitive deficits in dementia. The discovery could lead to new treatments that reduce excess immune activity in astrocytes and their detrimental effects on other brain ...

UC Irvine biologists discover bees to be brew masters of the insect world

2023-04-20

Irvine, Calif., April 20, 2023 — Scientists at the University of California, Irvine have made a remarkable discovery about cellophane bees – their microbiomes are some of the most fermentative known from the insect world. These bees, which are named for their use of cellophane-like materials to line their subterranean nests, are known for their fascinating behaviors and their important ecological roles as pollinators. Now, researchers have uncovered another aspect of their biology that makes them even more intriguing.

According to a study published in Frontiers in Microbiology, cellophane ...