(Press-News.org) Note to journaliststs. There are two linked press releases below: the first describes the scientific findings. The second describes the challenges of working in the Amazon forest.

How the Amazon rainforest is likely to cope with the effect of future drought

New study identifies regions in the rainforest most at risk from drier conditions

Drought will reduce the rainforest’s ability to remove carbon from the environment

A major collaboration involving 80 scientists from Europe and South America has identified the regions of the Amazon rainforest where trees are most likely to face the greatest risk from drier conditions brought about by climate change.

Based on the analysis, the scientists predict trees in the western and southern Amazon face the greatest risk of dying.

They also warn that previous scientific investigations may have underestimated the impact of drought on the rainforest because those studies focused on the central-eastern part of the forest, which is the least vulnerable to drought.

The latest study provides the first assessment across the entire Amazon Forest of how different areas are likely to respond to a climate that could get warmer and drier, and it comes as some studies predict the rainforest will experience increased periods of drought.

Professor David Galbraith, from the University of Leeds who supervised the study, said: “The Amazon is threatened by multiple stressors, including deforestation and climate. Understanding the stress limits that these forests can withstand is a major scientific challenge. Our study provides new insights into the limits of forest resistance to one major stressor - drought.”

Some parts of the Amazon have already seen changes in rainfall patterns. In the southern Amazon, there is evidence that the dry season has become longer, and temperatures in this region have increased more than in other parts of the Amazon. The changes in the southern Amazon are partially due to extensive deforestation.

Dr Julia Tavares, who led the study while undertaking a PhD at Leeds and is now based at Uppsala University in Sweden, said: “A lot of people think of the Amazon as one large forest.

“But it is not. It is made up of numerous forest regions that span different climate zones, from locations that are already very dry to those that are extremely wet, and we wanted to see how these different forest ecosystems are coping so we could begin to identify regions that are at particular risk of drought and drier conditions.”

Writing in the scientific journal Nature, the research team said their findings were removing a “...major knowledge bottleneck of how climate change will impact this critical ecosystem”.

The paper - “Basin-wide variation in tree hydraulic safety margins predicts the carbon balance of Amazon forests” - is published today (Wednesday, April 26. When the embargo lifts, the paper can be found at: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-023-05971-3).

Tree doctors

The research team, known as the “tree doctors” to the communities living in the forest, took measurements and samples over a year from 11 separate sites across the western, central-eastern and southern Amazon – covering Brazil, Peru and Bolivia.

The study involved data from 540 individual trees across 129 species.

The researchers wanted to determine how resistant different tree species and forests were to drought conditions. The scientists then used the data to test whether forest vulnerability to drought could predict its ability to accumulate and store carbon taken from the atmosphere.

From the data, the research team was able to quantify how safe the trees were from drought-related death.

Findings

In the southern part of the Amazon Forest, where historically there have been declining levels of rainfall, the trees showed the greatest degree of adaptation to cope with drought.

Despite that, though, the study revealed that the trees faced the biggest risk of dying due to drought. This is likely because the region has already seen rapid climate change and disruption to rainfall patterns caused by deforestation, which had pushed trees to the limits of their ability to cope.

In contrast, the tree species in the wettest parts of the Amazon Forest showed the lowest level of adaptation to drought yet they were the safest in terms of the risks from future climate change because, so far at least, they had not been impacted by changes in rainfall.

Equipped with this more nuanced view of how different parts of the Amazon Forest could respond to drought, the researchers warn that scientific investigations, which have tended to concentrate on the central-eastern region, where trees have shown some of the greatest adaptations to cope with drier conditions, may have underestimated how vulnerable other forest regions are to climate change.

They say the findings of the new study should be used to help update and refine existing models on how the Amazon may be impacted by drier conditions.

Carbon storage

According to the researchers, the Amazon Forest holds between ten and 15 percent of the carbon stored by vegetation globally, and it plays a key role in taking up carbon which would otherwise be in the atmosphere.

Modelling revealed that as plant drought mortality risk increases, the ability of the trees to store carbon would be significantly reduced. The most water stressed part of the Amazon is in the south-eastern region. Analysis reveals that the trees in this location no longer act as a large-scale carbon store.

Professor David Galbraith said: “This study reveals how forest risk to drought varies across the Amazon Basin and provides a mechanism for predicting carbon balance at the forest stand level. Forests that are ‘safer’ from drought-induced mortality are accumulating more carbon than those that face greater risk of drought-induced mortality.

Professor Emanuel Gloor, also from the University of Leeds who co-supervised the study, added: "The pattern of resilience and risks identified among the different tree populations across the in the study will be used to build more effective and accurate climate models of the way the Amazon may change as the region responds to climate change."

The study involved an international team of researchers from Europe, Brazil, Peru and Bolivia. The work was part of the TREMOR project funded by the UK’s Natural Environment Research Council to better understand mechanisms of tree mortality in Amazon forests and Julia’s PhD was supported by CAPES (Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel), Brazil.

END

Second Press Release

Scientists take a portable laboratory into the Amazon

As an ecologist, Dr Julia Tavares often has to consider how to collect data from remote locations.

But nothing had quite prepared her for the challenges she faced when she started her PhD at the University of Leeds.

As a doctoral researcher in the School of Geography, she took on the task of organising and eventually leading an expedition into the Amazon rainforest - and to record data from the dominant trees that existed at locations ranging from Brazil, Peru and Bolivia.

The study involved overseeing the harvesting of hundreds of tissue samples, work which had to take place in the middle of the night, all in the quest of cutting-edge science.

The research team worked in extreme humidity and temperatures that reached 30 degrees Celsius by eight in the morning and over 35 degrees by midday. And the hot and humid conditions brought out clouds of mosquitoes.

Involving a collaboration of 80 scientists and support staff, the study was looking at how different tree species had adapted to drought, and how vulnerable different forest zones would be to further climate change.

It was the first investigation into the water stress faced by trees across the entire Amazon basin and how they might cope if, as some climate models predict, the Amazon gets significantly warmer and rainfall patterns change.

The findings of the research have been published today in the scientific journal Nature. (Wednesday, April 26. When the embargo lifts, the paper can be found at: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-023-05971-3).

Sampling from the tree canopy

Samples were taken from more than 540 trees. These were the dominant canopy species, with some reaching over 30 meters in height. The tissue samples were used to measure how hydrated the tress were, and this fluctuates over a 24-hour period.

The scientists needed to measure hydration during periods of low and high-water stress. To do that, sampling was done at three in the morning - when the rainforest was in utter darkness and plants were recharging their water levels - and again at midday.

As part of the expedition, the scientific team brought a mobile laboratory, packed in 16 flight cases, into the forest along with giant cylinders of nitrogen gas.

Dr Tavares said: “We had a team of expert tree climbers whose job it was to use ropes and climbing gear to ascend the trees and get the samples.

“We would survey the site the day before we intended to take the samples. Remember, we were working in a dense rainforest and some of the sampling was happening at night, so we needed to mark the trees and the branches that we wanted for the tissue samples.”

The trees climbers used what are telescopic scissors, which can extend six or so metres, to reach out across the vegetation and harvest the branch they were after.

Dr Carol Signori-Muller, an ecophysiologist formerly at University of Campinas, Brazil, and now with the University of Exeter, said the rainforest is a beautiful and fantastic place that took on a different character at night.

She said: “At night it is very dark. The moonlight can be blocked out by the dense overhead vegetation. And it is very silent.

“There is hardly any sound from the birds. All you can hear are the croaking of frogs or the movement of branches. You become attuned to the sounds around you because you need to be aware that something can suddenly appear from behind a bush.”

During one off the daytime sampling sessions, a jaguar emerged from the undergrowth and started playing with the ropes attached to the climbing gear, in the way a cat would play with a ball of wool.

Dr Tavares added: “The team had to stop what we were doing and keep away - and just watch the jaguar, who did end up destroying some of the climbing gear.”

Reaching the different forest locations would involve a drive in four-by-four vehicles or by boat and would involve the scientists and support staff camping or staying in field station accommodation.

The team wore long boots to protect themselves from the snakes that live in the rainforest.

The results of the study will help identify those regions of the rainforest at greatest risk from climate change, enabling conservationists to target resources and policies to those areas.

Dr Halina Soares Jancoski, who took part in the expedition while at the State University of Mato Grosso in Brazil and is now with the Environment Secretariat of the Municipality of Nova Xavantina, in the central west region of Brazil, said: “I consider this study very important because it helps us to understand how forests will behave with the effect of climate change. Especially in the Amazon - Cerrado transition areas, which are more susceptible to climate extremes than in the core areas.”

Dr Tavares added: “At the start of my PhD, if you said to me that I would be involved in a major expedition into the Amazon and would have led a scientific collaboration into one of the most important ecological questions facing this hugely important ecosystem, I would have thought you were joking.

“But, together with an amazing team, that is exactly what we have done.”

END

END

How the Amazon rainforest is likely to cope with the effect of future drought

2023-04-26

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Neuronal activity shapes the development of astrocytes

2023-04-26

Researchers at Baylor College of Medicine have unraveled the processes that give astrocytes, the most abundant glial cell in the brain, their special bushy shape, which is fundamental for brain function. They report in the journal Nature that neuronal activity is necessary and sufficient for astrocytes to develop their complex shape, and interrupting this developmental process results in disrupted brain function.

“Astrocytes play diverse roles that are vital for proper brain function,” said first author Yi-Ting Cheng, a graduate student in Dr. Benjamin Deneen’s lab at Baylor. “For instance, they support the activity of other essential brain cells, ...

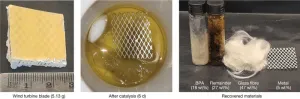

New chemistry can extract virgin-grade materials from wind turbine blades in one process

2023-04-26

The new chemical process is not limited to wind turbine blades but works on many different so-called fibre-reinforced epoxy composites, including some materials that are reinforced with especially costly carbon fibres.

Thus, the process can contribute to establishing a potential circular economy in the wind turbine, aerospace, automotive and space industries, where these reinforced composites, due to their light weight and long durability, are used for load-bearing structures.

Being designed to last, the durability of the blades poses an ...

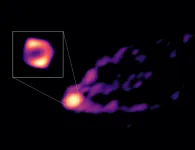

Astronomers image for the first time a black hole’s shadow together with a powerful jet

2023-04-26

"Previously we had seen both the black hole and the jet in separate images, but now we have taken a panoramic picture of the black hole together with its jet at a new wavelength”, says Ru-Sen Lu, from the Shanghai Astronomical Observatory and leader of a Max Planck Research Group at the Chinese Academy of Sciences. The surrounding material is thought to fall into the black hole in a process known as accretion. But no one has ever imaged it directly. "The ring that we have seen before is becoming larger and thicker at 3.5 mm observing wavelength. This shows that the material falling into the black hole produces additional emission that is now observed in the new ...

New black hole images reveal a glowing, fluffy ring and a high-speed jet

2023-04-26

In 2017, astronomers captured the first image of a black hole by coordinating radio dishes around the world to act as a single, planet-sized telescope. The synchronized network, known collectively as the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT), focused in on M87*, the black hole at the center of the nearby Messier 87 galaxy. The telescope’s laser-focused resolution revealed a very thin glowing ring around a dark center, representing the first visual of a black hole’s shadow.

Astronomers have now refocused their view to capture a new layer of M87*. The team, including scientists at MIT’s Haystack Observatory, has harnessed ...

Astronomers double number of known repeating fast radio bursts

2023-04-26

Astronomers in the Canadian-led CHIME/FRB Collaboration have doubled the number of known repeating sources of mysterious flashes of radio waves, known as fast radio bursts (FRBs). Among them are astronomers from the University of Toronto. Through the discovery of 25 new repeating sources (for a total of 50), the team also solidified the idea that all FRBs may eventually repeat.

FRBs are considered one of the biggest mysteries in astronomy, but their exact origins are unknown. Astronomers do know that they come from far outside of our Milky Way, and are likely produced by the cinders left behind after stars die. Most of the thousands of FRBs that astronomers have discovered to ...

First direct image of a black hole expelling a powerful jet

2023-04-26

For the first time, astronomers have observed, in the same image, the shadow of the black hole at the centre of the galaxy Messier 87 (M87) and the powerful jet expelled from it. The observations were done in 2018 with telescopes from the Global Millimetre VLBI Array (GMVA), the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), of which ESO is a partner, and the Greenland Telescope (GLT). Thanks to this new image, astronomers can better understand how black holes can launch such energetic jets.

Most galaxies harbour a supermassive black hole at their centre. While black holes are known for ...

MD Anderson’s Hagop Kantarjian, M.D., awarded highest honor from American Society of Clinical Oncology

2023-04-26

The American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) will present the 2023 David A. Karnofsky Memorial Award to Hagop Kantarjian, M.D., chair of Leukemia at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, for his contributions to leukemia clinical research and his dedication to improving the lives of patients.

“Cancer research and patient care have been my life’s passion and mission and, I am honored to be recognized by ASCO with the society’s highest scientific award,” Kantarjian said. “I am grateful for all of the outstanding investigators in the Leukemia Department and outside ...

Bioindicator for the occurrence of PFAS

2023-04-26

The researchers focused on 66 PFAS compounds for their study. These can be grouped into three categories: 1) PFAS groups that have been regulated for some time; 2) new PFAS that industry uses as substitutes for regulated PFAS; and 3) precursors that can degrade to other, more persistent PFAS. However, because these individual analyses can detect only a small fraction of the more than 10,000 PFAS used by industry and because many polyfluorinated compounds cannot be measured because of the lack of analytical ...

Prolonged droughts likely spelled the end for Indus megacities

2023-04-26

New research involving Cambridge University has found evidence — locked into an ancient stalagmite from a cave in the Himalayas — of a series of severe and lengthy droughts which may have upturned the Bronze Age Indus Civilization.

The beginning of this arid period — starting at around 4,200 years ago and lasting for over two centuries — coincides with the reorganization of the metropolis-building Indus Civilization, which spanned present-day Pakistan and India.

The research ...

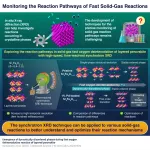

Advanced X-ray technique unveils fast solid-gas chemical reaction pathways

2023-04-26

For the rational design of new material compounds, it is important to understand the mechanisms underlying their synthesis. Analytical techniques such as nuclear magnetic resonance and spectroscopy are usually employed to study such mechanisms in molecular reactions. However, reaction pathways governing the formation of solid-state crystalline compounds remain poorly understood. This is partly due to the extreme temperatures and inhomogeneous reactions observed in solid-state compounds. Further, the presence of numerous atoms in solid crystalline compounds ...