(Press-News.org) Storing data in DNA sounds like science fiction, yet it lies in the near future. Professor Tom de Greef expects the first DNA data center to be up and running within five to ten years. Data won’t be stored as zeros and ones in a hard drive but in the base pairs that make up DNA: AT and CG. Such a data center would take the form of a lab, many times smaller than the ones today. De Greef can already picture it all. In one part of the building, new files will be encoded via DNA synthesis. Another part will contain large fields of capsules, each capsule packed with a file. A robotic arm will remove a capsule, read its contents and place it back.

We’re talking about synthetic DNA. In the lab, bases are stuck together in a certain order to form synthetically produced strands of DNA. Files and photos that are currently stored in data centers can then be stored in DNA. For now, the technique is suitable only for archival storage. This is because the reading of stored data is very expensive, so you want to consult the DNA files as little as possible.

Large, energy-guzzling data centers made obsolete

Data storage in DNA offers many advantages. A DNA file can be stored much more compactly, for instance, and the lifespan of the data is also many times longer. But perhaps most importantly, this new technology renders large, energy-guzzling data centers obsolete. And this is desperately needed, warns De Greef, “because in three years, we will generate so much data worldwide that we won’t be able to store half of it.”

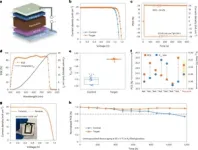

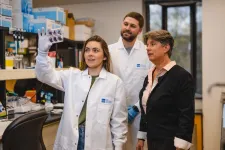

Together with PhD student Bas Bögels, Microsoft and a group of university partners, De Greef has developed a new technique to make the innovation of data storage with synthetic DNA scalable. The results have been published today in the journal Nature Nanotechnology. De Greef works at the Department of Biomedical Engineering and the Institute for Complex Molecular Systems (ICMS) at TU Eindhoven and serves as a visiting professor at Radboud University.

Scalable

The idea of using strands of DNA for data storage emerged in the 1980s but was far too difficult and expensive at the time. It became technically possible three decades later, when DNA synthesis started to take off. George Church, a geneticist at Harvard Medical School, elaborated on the idea in 2011. Since then, synthesis and the reading of data have become exponentially cheaper, finally bringing the technology to the market.

In recent years, De Greef and his group have looked mainly into reading the stored data. For the time being, this is the biggest problem facing this new technique. The PCR method currently used for this, called ‘random access’, is highly error-prone. You can therefore only read one file at a time and, in addition, the data quality deteriorates too much each time you read a file. Not exactly scalable.

Here’s how it works: PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) creates millions of copies of the piece of DNA that you need by adding a primer with the desired DNA code. Corona tests in the lab, for example, are based on this: even a minuscule amount of coronavirus material from your nose is detectable when copied so many times. But if you want to read multiple files simultaneously, you need multiple primer pairs doing their work at the same time. This creates many errors in the copying process.

Every capsule contains one file

This is where the capsules come into play. De Greef’s group developed a microcapsule of proteins and a polymer and then anchored one file per capsule. De Greef: “These capsules have thermal properties that we can use to our advantage.” Above 50 degrees Celsius, the capsules seal themselves, allowing the PCR process to take place separately in each capsule. Not much room for error then. De Greef calls this ‘thermo-confined PCR’. In the lab, it has so far managed to read 25 files simultaneously without significant error.

If you then lower the temperature again, the copies detach from the capsule and the anchored original remains, meaning that the quality of your original file does not deteriorate. De Greef: “We currently stand at a loss of 0.3 percent after three reads, compared to 35 percent with the existing method.”

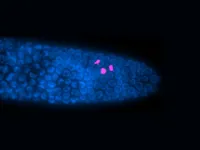

Searchable with fluorescence

And that’s not all. De Greef has also made the data library even easier to search. Each file is given a fluorescent label and each capsule its own color. A device can then recognize the colors and separate them from one another. This brings us back to the imaginary robotic arm at the beginning of this story, which will neatly select the desired file from the pool of capsules in the future.

This solves the problem of reading the data. De Greef: “Now it’s just a matter of waiting until the costs of DNA synthesis fall further. The technique will then be ready for application.” As a result, he hopes that the Netherlands will soon be able to open its inaugural DNA data center – a world first.

This paper appeared in the journal Nature Nanotechnology under the title ‘DNA storage in thermoresponsive microcapsules for repeated random multiplexed data access’. DOI: 10.1038/s41565-023-01377-4. Industrial partners: Microsoft. University partners: University of Washington, Radboud University, University of Bristol, Shanghai Jiao Tong University. Partnerships: Center for Living Technologies, Eindhoven-Wageningen-Utrecht Alliance

END

The future of data storage lies in DNA microcapsules

DNA archival storage within reach thanks to new PCR technique

2023-05-04

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Quantum computer in reverse gear

2023-05-04

Today's computers are based on microprocessors that execute so-called gates. A gate can, for example, be an AND operation, i.e. an operation that adds two bits. These gates, and thus computers, are irreversible. That is, algorithms cannot simply run backwards. “If you take the multiplication 2*2=4, you cannot simply run this operation in reverse, because 4 could be 2*2, but likewise 1*4 or 4*1,” explains Wolfgang Lechner, professor of theoretical physics at the University of Innsbruck. If this were possible, however, it would be feasible ...

Seizure discoveries advance efforts to develop better treatments

2023-05-04

New University of Virginia School of Medicine insights into how the brain responds to seizures could facilitate the development of much-needed treatments for the third of patients who don’t respond to existing options.

The research, from the labs of UVA’s Ukpong B. Eyo, PhD, and Edward Perez-Reyes, PhD, suggests that immune cells called microglia play important, beneficial roles in controlling various types of seizures. Prior research had left scientists uncertain whether these cells were helpful or harmful during the brain’s ...

Taylor & Francis set to open over 50 book titles with Knowledge Unlatched

2023-05-04

Taylor & Francis is delighted to announce the results of Knowledge Unlatched (KU) 2023, with support pledged to convert over 50 book titles to open access (OA). Titles to benefit from this support cover a broad range of humanities and social science disciplines as well as key topic areas, including climate change, global health, and gender studies.

Under the KU crowdfunding model, research libraries around the world unite to support the publication costs of new eBooks and enable access for all to important new research. Since 2016, when Taylor & Francis’ partnership with Knowledge Unlatched began, over 100 books have been published OA at no cost ...

Obesity as a risk factor for colorectal cancer underestimated so far

2023-05-04

Obesity is a known risk factor for colorectal cancer. Scientists at the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ) have now shown that this association has probably been significantly underestimated so far. The reason: many people unintentionally lose weight in the years before a colorectal cancer diagnosis. If studies only consider body weight at the time of diagnosis, this obscures the actual relationship between obesity and colorectal cancer risk. In addition, the current study shows that unintentional weight loss may be an early indicator of colorectal ...

Happy worms have healthy eggs

2023-05-04

Worms might not be depressed, per se. But that doesn’t mean they can’t benefit from antidepressants.

In a new study, Northwestern University researchers exposed roundworms (a well-established model organism in biological research) to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), a class of drugs used for treating depression and anxiety. Surprisingly, this treatment improved the quality of aging females’ egg cells.

Not only did exposure to SSRIs decrease embryonic death by more than twofold, it also decreased chromosomal abnormalities in surviving offspring by more than twofold. Under the microscope, ...

New guidance to help diagnose hoarding disorder

2023-05-04

Experts from Anglia Ruskin University (ARU) have published new guidance to help doctors correctly diagnose hoarding disorder.

Hoarding disorder affects around 2% of the population but remains a largely misunderstood mental health condition. It was only added to the International Classification of Diseases in 2019, having previously been classified under Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD).

Published in the British Journal of General Practice, the new guidance was written by Dr Sharon Morein and Dr Sanjiv Ahluwalia of Anglia Ruskin University (ARU) in Cambridge, England, to help health professionals spot the signs of hoarding disorder and intervene.

ARU experts have also organised a free ...

GlyNAC supplementation improves cognitive decline and brain health in aging

2023-05-04

As people get older, they aspire to live healthy lives as free as possible from the natural decline of cognitive abilities that occurs with aging. At Baylor College of Medicine, researchers have been studying the biological underpinnings of age-associated cognitive decline and developing nutritional strategies to promote healthy brain aging.

They report today in the journal Antioxidants that supplementing GlyNAC – a combination of glycine and N-acetylcysteine as precursors of the natural antioxidant glutathione – improved or reversed age-associated cognitive decline in old mice and improved ...

Three NYU faculty elected to the National Academy of Sciences

2023-05-04

Three New York University faculty have been elected to the National Academy of Sciences: Moses Chao, a professor at NYU Grossman School of Medicine; Glennys Farrar, a professor in NYU’s Department of Physics; and Subhash Khot, a professor in NYU’s Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences. This year’s election of 120 new members and 23 international members were chosen “in recognition of their distinguished and continuing achievements in original research,” the academy announced.

Moses Chau, a professor of cell biology, psychiatry, and neuroscience and physiology and part of ...

Criteria for selecting who can enroll in multiple myeloma clinical trials may exclude patients from racial and ethnic minorities

2023-05-04

(WASHINGTON, May 4, 2023) – Numerous studies have shown that people from racial and ethnic minority groups are underrepresented in clinical trials of new medical treatments for multiple myeloma. A study published today in Blood suggests that, for clinical trials of new treatments for multiple myeloma (a type of blood cancer), one reason for this underrepresentation may be that the parameters set to determine who can – and cannot – enroll in trials disproportionately exclude minority patients.

“Our ...

Wistar scientists discover innate tumor suppression mechanism

2023-05-04

PHILADELPHIA — (MAY 4, 2023) — The p53 gene is one of the most important in the human genome: the only role of the p53 protein that this gene encodes is to sense when a tumor is forming and to kill it. While the gene was discovered more than four decades ago, researchers have so far been unsuccessful at determining exactly how it works. Now, in a recent study published in Cancer Discovery, a journal of the American Association for Cancer Research, researchers at The Wistar Institute have uncovered a key mechanism ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

UCSB scientists bottle the sun with liquid battery

Lung cancer drug offers a surprising new treatment against ovarian cancer

When consent meets reality: How young men navigate intimacy

Siemens Healthineers and Mayo Clinic expand strategic collaboration to enhance patient care through advanced technology

Physicists develop new protocol for building photonic graph states

OHSU-led research initiative examines supervised psilocybin

New review identifies pathways for managing PFAS waste in semiconductor manufacturing

New research finds state-level abortion restrictions associated with increased maternal deaths

New study assesses potential dust control options for Great Salt Lake

Science policy education should start on campus

Look again! Those wrinkly rocks may actually be a fossilized microbial community

Exposure to intense wildfire smoke during pregnancy may be linked to increased likelihood of autism

Children with Crohn’s have distinct gut bacteria from kids with other digestive disorders

Genomics offers a faster path to restoring the American chestnut

Caught in the act: Astronomers watch a vanishing star turn into a black hole

Why elephant trunk whiskers are so good at sensing touch

A disappearing star quietly formed a black hole in the Andromeda Galaxy

Yangtze River fishing ban halts 70 years of freshwater biodiversity decline

Genomic-informed breeding approaches could accelerate American chestnut restoration

How plants control fleshy and woody tissue growth

Scientists capture the clearest view yet of a star collapsing into a black hole

New insights into a hidden process that protects cells from harmful mutations

Yangtze River fishing ban halts seven decades of biodiversity decline

Researchers visualize the dynamics of myelin swellings

Cheops discovers late bloomer from another era

Climate policy support is linked to emotions - study

New method could reveal hidden supermassive black hole binaries

Novel AI model accurately detects placenta accreta in pregnancy before delivery, new research shows

Global Physics Photowalk winners announced

Exercise trains a mouse's brain to build endurance

[Press-News.org] The future of data storage lies in DNA microcapsulesDNA archival storage within reach thanks to new PCR technique