(Press-News.org) Air pollution has been shown to have a negative effect on the prognosis of ischemic stroke, or stroke caused by reduced blood flow to the brain, but the exact mechanism is unknown. A team of researchers recently conducted a study to determine whether or not increased inflammation of the brain, also known as neuroinflammation, is the main culprit.

The team published their findings in the February 16, 2023 issue of Particle and Fibre Toxicology.

Mice exposed intranasally to urban aerosols from Beijing, China, for one week demonstrated increased neuroinflammation and worsening movement disorder after ischemic stroke, compared to control mice that were not exposed to air pollution. Additionally, this effect was not observed in urban-aerosol treated mice lacking a receptor for chemicals released by the burning of fossil fuels, wood, garbage and tobacco, called polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH). This suggests that PAHs are involved in both neuroinflammation and increased movement disorder associated with air pollution exposure in ischemic stroke.

“We designed this study to determine the effects of air pollution on disorders in the central nervous system,” said Yasuhiro Ishihara, senior author of the research paper and professor in the Graduate School of Integrated Sciences for Life at Hiroshima University. “Our narrower focus was to determine whether or not the prognosis of ischemic stroke was affected by air pollution,” said Ishihara.

The group went one step further by identifying specific components of air pollution that may directly contribute to lower prognoses in ischemic stroke.

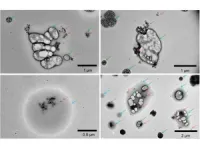

They found evidence that intranasal exposure to air pollution from Beijing, China, increased neuroinflammation after ischemic stroke in mice through activation of microglial cells, which are immune cells found in the brain. Movement disorder was also negatively impacted in ischemic stroke mice exposed to the same air pollution. A second set of experiments replacing Beijing air pollution with PM2.5 (tiny, aerosolized particles of air pollution that are 2.5 microbes in width or less) from Yokohama, Japan demonstrated similar results, suggesting the PM2.5 fraction of urban air pollution contains the chemical responsible for increased neuroinflammation and decreased ischemic stroke prognosis.

In order to identify chemicals in air pollution responsible for decreased ischemic stroke prognosis, the research team used a mouse that lacked the aryl hydrocarbon receptor, a receptor that is activated by the presence of PAHs, to determine whether or not exposure to the Beijing air pollution would have the similar effect on mice without working aryl hydrocarbon receptors. Mice lacking the aryl hydrocarbon receptor demonstrated lower microglial cell activation and movement disorder compared to normal mice, suggesting that the PAHs present in Beijing air pollution are responsible for at least some of the neuroinflammation and lower prognosis seen in ischemic stroke mice exposed to air pollution.

Ultimately, the goal of the research team is to better understand the mechanism by which PM2.5 causes neuroinflammation, since air pollution is inhaled first into the respiratory tract. “Can small particles move from the nose to the brain? Does lung or systemic inflammation affect the brain immune system?” said Ishihara.

##

Other contributors include Nami Ishihara and Ami Oguro from the Program for Biomedical Science in the Graduate School of Integrated Sciences for Life at Hiroshima University in Higashi-Hiroshima, Japan; Miki Tanaka from Program for Biomedical Science in the Graduate School of Integrated Sciences for Life at Hiroshima University and the Laboratory for Pharmacotherapy and Experimental Neurology in the Kagawa School of Pharmaceutical Sciences at Tokushima Bunri University in Sanuki, Japan; Kouichi Itoh from the Laboratory for Pharmacotherapy and Experimental Neurology in the Kagawa School of Pharmaceutical Sciences at Tokushima Bunri University; Tomoaki Okuda from the Faculty of Science and Technology at Keio University in Yokohama, Japan; Yoshiaki Fujii-Kuriyama from the Medical Research Institute in Molecular Epidemiology at the Tokyo Medical and Dental University in Tokyo, Japan; Yu Nabetani from the Department of Applied Chemistry in the Faculty of Engineering at the University of Miyazaki in Miyazaki, Japan; Megumi Yamamoto from the Department of Environment and Public Health at the National Institute of Minamata Disease in Minamata, Japan; Christoph F. A. Vogel from the Department of Environmental Toxicology and the Center for Health and the Environment at the University of California Davis in Davis, California.

This work was supported by Research Fellowships for Young Scientists (Grant Number 20J10103), KAKENHI Grants from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (Grant Numbers 21K06702, 20H04341, 17H04714, 15KK0024), the Environmental Research and Technology Development Funds of the Environmental Restoration and Conservation Agency of Japan (Grant Numbers JPMEERF20165051 and JPMEERF20205007) and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (Grant Numbers R01ES029126 and R01ES032827).

About Hiroshima University

Since its foundation in 1949, Hiroshima University has striven to become one of the most prominent and comprehensive universities in Japan for the promotion and development of scholarship and education. Consisting of 12 schools for undergraduate level and 5 graduate schools, ranging from natural sciences to humanities and social sciences, the university has grown into one of the most distinguished comprehensive research universities in Japan. English website: https://www.hiroshima-u.ac.jp/en

END

Air pollution worsens movement disorder after stroke

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, in particular, lower the prognosis of ischemic strokes by causing inflammation in the brain.

2023-05-10

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Most antidepressants prescribed for chronic pain lack reliable evidence of efficacy or safety, scientists warn

2023-05-10

Largest ever investigation into antidepressants used for chronic pain shows insufficient evidence to determine how effective or harmful they may be

Study reviewed commonly prescribed medications including amitriptyline, duloxetine, fluoxetine, citalopram, paroxetine, and sertraline

One third of people globally are living with long-term pain with many prescribed antidepressants to relieve symptoms

Most antidepressants used for chronic pain are being prescribed with “insufficient” evidence of their effectiveness, scientists have warned.

A major investigation into medications used to manage long-term pain found that ...

Dark clouds on the horizon

2023-05-10

Our industrialized society releases many and various pollutants into the world. Combustion in particular produces aerosol mass including black carbon. Although this only accounts for a few percent of aerosol particles, black carbon is especially problematic due to its ability to absorb heat and impede the heat reflection capabilities of surfaces such as snow. So, it’s essential to know how black carbon interacts with sunlight. Researchers have quantified the refractive index of black carbon to the most accurate degree yet which might impact climate models.

There are many factors driving climate change; some are very familiar, such ...

Scientists discover microbes in the Alps and Arctic that can digest plastic at low temperatures

2023-05-10

Finding, cultivating, and bioengineering organisms that can digest plastic not only aids in the removal of pollution, but is now also big business. Several microorganisms that can do this have already been found, but when their enzymes that make this possible are applied at an industrial scale, they typically only work at temperatures above 30°C. The heating required means that industrial applications remain costly to date, and aren’t carbon-neutral. But there is a possible solution to this problem: ...

Salt marshes protect the coast – but not where it is needed most

2023-05-10

Salt marshes provide multiple ecosystem services, one of those is protection of the coast against flooding. This is especially important in low-lying countries like the Netherlands. Scientists from the University of Groningen and the Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research (NIOZ), in collaboration with the local water authority, have monitored wave run-up during storms over a three-year period. The results, which were published in the Journal of Applied Ecology on 10 May, help the water authority to quantify the protective effect of salt marshes.

For three years, ecologist Beatriz Marin-Diaz always had one eye on the weather ...

New USC study shows immigrant adults with liver cancer have higher survival rates than those born in the US

2023-05-10

Immigrant adults with liver cancer in the United States have higher survival rates than people with the disease who were born in the U.S., according to new research from the USC Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the most common form of liver cancer, contributes to more than 27,000 deaths annually in the United States. Immigrants comprise a significant proportion of those diagnosed with HCC in the U.S. Research has shown that birthplace, also referred to as nativity, impacts incidence and risk factors for HCC, but little was known about its influence on survival after diagnosis.

The new study, just published in the Journal of the National ...

Physicists discover ‘stacked pancakes of liquid magnetism’

2023-05-10

HOUSTON – (May 10, 2023) – Physicists have discovered “stacked pancakes of liquid magnetism” that may account for the strange electronic behavior of some layered helical magnets.

The materials in the study are magnetic at cold temperatures and become nonmagnetic as they thaw. Experimental physicist Makariy Tanatar of Ames National Laboratory at Iowa State University noticed perplexing electronic behavior in layered helimagnetic crystals and brought the mystery to the attention of Rice theoretical physicist Andriy Nevidomskyy, who worked with Tanatar and former Rice graduate student Matthew Butcher to create a computational model that simulated the quantum states ...

Workplace accidents are most likely to occur in moderately dangerous settings

2023-05-10

Although some people might expect very dangerous jobs to be associated with the highest incidence of workplace accidents, a new study finds that accidents are actually most likely to occur within moderately dangerous work environments.

“In highly dangerous environments, individuals engage in a high degree of safety behaviours, which offsets the chance of an accident,” said Dr. James Beck, lead author and a professor of psychology. “On the other hand, in moderately dangerous environments, people usually engage in some safety behaviours, yet most people do not engage in enough safety ...

Training machines to learn more like humans do

2023-05-09

Imagine sitting on a park bench, watching someone stroll by. While the scene may constantly change as the person walks, the human brain can transform that dynamic visual information into a more stable representation over time. This ability, known as perceptual straightening, helps us predict the walking person’s trajectory.

Unlike humans, computer vision models don’t typically exhibit perceptual straightness, so they learn to represent visual information in a highly unpredictable way. But if machine-learning models had this ability, it might enable them to better estimate how objects or people will move.

MIT researchers have discovered that a specific training ...

New UCF-developed immunotherapy treatment targets respiratory viral infections

2023-05-09

ORLANDO, May 9, 2023 – A University of Central Florida College of Medicine researcher has developed a new, more precise treatment for a major cause of illness around the world each year — acute respiratory viral infections.

Acute respiratory viral infections include sicknesses such as the flu, pneumonia, respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and coronavirus. These infections cause millions of illnesses worldwide, with the flu alone responsible for 3 million to 5 million cases of severe illness and up to 650,000 respiratory deaths each year, ...

McMaster researchers find best treatment for excessive daytime sleepiness

2023-05-09

Hamilton, ON (March 9, 2023) – McMaster University researchers Dena Zeraatkar and Tyler Pitre have found that the drug solriamfetol is the most effective treatment for excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) for people with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA).

The standard treatment for OSA is a positive airway pressure (PAP) mask that uses compressed air to support lung airways during sleep. However, some people with OSA still experience EDS and may benefit from anti-fatigue medication.

Zeraatkar ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

HPV vaccination provides “sustained protection” against cervical cancer

Many post-authorization studies fail to comply with public disclosure rules

GLP-1 drugs combined with healthy lifestyle habits linked with reduced cardiovascular risk among diabetes patients

Solved: New analysis of Apollo Moon samples finally settles debate about lunar magnetic field

University of Birmingham to host national computing center

Play nicely: Children who are not friends connect better through play when given a goal

Surviving the extreme temperatures of the climate crisis calls for a revolution in home and building design

The wild can be ‘death trap’ for rescued animals

New research: Nighttime road traffic noise stresses the heart and blood vessels

Meningococcal B vaccination does not reduce gonorrhoea, trial results show

AAO-HNSF awarded grant to advance age-friendly care in otolaryngology through national initiative

Eight years running: Newsweek names Mayo Clinic ‘World’s Best Hospital’

Coffee waste turned into clean air solution: researchers develop sustainable catalyst to remove toxic hydrogen sulfide

Scientists uncover how engineered biochar and microbes work together to boost plant-based cleanup of cadmium-polluted soils

Engineered biochar could unlock more effective and scalable solutions for soil and water pollution

Differing immune responses in infants may explain increased severity of RSV over SARS-CoV-2

The invisible hand of climate change: How extreme heat dictates who is born

Surprising culprit leads to chronic rejection of transplanted lungs, hearts

Study explains how ketogenic diets prevent seizures

New approach to qualifying nuclear reactor components rolling out this year

U.S. medical care is improving, but cost and health differ depending on disease

AI challenges lithography and provides solutions

Can AI make society less selfish?

UC Irvine researchers expose critical security vulnerability in autonomous drones

Changes in smoking status and their associations with risk of Parkinson’s, death

In football players with repeated head impacts, inflammation related to brain changes

Being an early bird, getting more physical activity linked to lower risk of ALS

The Lancet: Single daily pill shows promise as replacement for complex, multi-tablet HIV treatment regimens

Single daily pill shows promise as replacement for complex, multi-tablet HIV treatment regimens

Black Americans face increasingly higher risk of gun homicide death than White Americans

[Press-News.org] Air pollution worsens movement disorder after strokePolycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, in particular, lower the prognosis of ischemic strokes by causing inflammation in the brain.