(Press-News.org) With each breath, humans exhale more than 1,000 distinct molecules, producing a unique chemical fingerprint or “breathprint” rich with clues about what’s going on inside the body.

For decades, scientists have sought to harness that information, turning to dogs, rats and even bees to literally sniff out cancer, diabetes, tuberculosis and more.

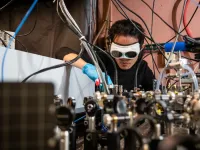

Scientists from CU Boulder and the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) have made an important leap forward in the quest to diagnose disease using exhaled breath, reporting that a new laser-based breathalyzer powered by artificial intelligence (AI) can detect COVID-19 in real-time with excellent accuracy.

The results were published April 5 in the Journal of Breath Research.

“Our results demonstrate the promise of breath analysis as an alternative, rapid, non-invasive test for COVID-19 and highlight its remarkable potential for diagnosing diverse conditions and disease states,” said first author Qizhong Liang, a PhD candidate in JILA and the Department of Physics at CU Boulder. JILA is a partnership between CU Boulder and NIST.

The multidisciplinary team of physicists, biochemists and biologists is now shifting its focus to a wide range of other diseases in hopes that the “frequency comb breathalyzer”—born of Nobel Prize-winning technology from CU—could revolutionize medical diagnostics.

“There is a real, foreseeable future in which you could go to the doctor and have your breath measured along with your height and weight…Or you could blow into a mouthpiece integrated into your phone and get information about your health in real-time,” said senior author Jun Ye, a JILA fellow and adjoint professor of physics at CU Boulder. “The potential is endless.”

A COVID-born collaboration

As far back as 2008, Ye’s lab reported that a technique called frequency comb spectroscopy—essentially using laser light to distinguish one molecule from another—could potentially identify biomarkers of disease in human breath.

The technology lacked sensitivity and, more importantly, the capability to link specific molecules to disease states, so they never tested it for diagnosing illness.

But Ye’s team has since improved the sensitivity a thousandfold, enabling detection of trace molecules at the parts-per-trillion level. They’ve also harnessed the power of AI.

“Molecules increase or decrease in concentrations when associated with specific health conditions,” said Liang. “Machine learning analyzes this information, identifies patterns and develops criteria we can use to predict a diagnosis.”

With SARS-CoV-2 ripping across the country and frustration mounting about long response times for existing tests, the time had come to test the system on people. As a physicist, Ye had never worked with human subjects, so he enlisted help from CU’s BioFrontiers Institute, an interdisciplinary hub for biomedical research which was heading up the campus COVID testing program.

The National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health funded the research.

Non-invasive, fast, chemical-free

Between May 2021 and January 2022, the research team collected breath samples from 170 CU Boulder students who had, in the previous 48 hours, taken a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test, either by submitting a saliva or a nasal sample.

Half had tested positive, half negative. (For safety reasons, volunteer participants came to an outdoor campus parking lot, blew in a sample-collection bag and left it for a lab tech waiting at a safe distance.)

Overall, the process took less than one hour from collection to result.

When compared to PCR, the gold standard COVID test, breathalyzer results matched 85% of the time. For medical diagnostics, accuracy of 80% or greater is considered “excellent.”

The resesarchers suspect that the accuracy would likely have been higher if the breath and saliva/nasal swab samples were collected at the same time.

Unlike a nasal swab, the breathalyzer is non-invasive. And unlike a saliva sample, users are not asked to refrain from eating, drinking or smoking before using it. It doesn’t require costly chemicals to break down the sample. And the new test could, conceivably, be used on individuals who are not conscious.

But there is still much to be learned, said Ye.

“With one breath, we can collect so many data points from you, but then what? We only understand how a few molecules correlate with specific conditions,” Ye said.

Building a smaller breathalyzer

Today, the “breathalyzer” consists of a complex array of lasers and mirrors about the size of a banquet table.

A breath sample is piped in through a tube as lasers fire invisible mid-infrared light at it at thousands of different frequencies. Dozens of tiny mirrors bounce the light back and forth through the molecules so many times that in the end, the light travels about 1.5 miles.

Because each kind of molecule absorbs light differently, breath samples with a different molecular make-up cast distinct shadows. The machine can distinguish between those different shadows or absorption patterns, boiling millions of data points down to—in the case of COVID—a simple positive or negative, in a matter of seconds.

Efforts are already underway to miniaturize such systems to a chip scale, allowing for what Liang imagines as “real-time, self-health monitoring on the go.” The potential does not end there.

“What if you could find a signature in breath that could detect pancreatic cancer before you were even symptomatic. That would be the home run,” said molecular biologist and co-author Leslie Leinwand, chief scientific officer for BioFrontiers and a co-author on the study

Elsewhere, scientists are working to develop a Human Breath Atlas, which maps each molecule in the human exhale and correlates them with health outcomes. Liang hopes to contribute to such efforts with a larger-scale collection of breath samples.

Meanwhile, the team is collaborating with pediatric and respiratory specialists at the CU Anschutz Medical Campus to explore how the breathalyzer can not only diagnose diseases but also enable scientists to better understand them, offering hints about immune responses, nutritional deficiencies and other factors that could contribute to or exacerbate illness.

“If you think about dogs, they evolved over thousands of years to smell many different things with remarkable sensitivity,” said Ye. “We are just at the very beginning of training our laser-based nose. The more we teach it, the smarter it will be come.”

END

New breathalyzer for disease sniffs out COVID in real-time, could be used to detect cancer, lung disease

Quantum laser-based technology a big step forward toward using exhaled breath to diagnose illness

2023-05-10

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Home measurement of blood oxygen levels by corona patients themselves easily applicable

2023-05-10

May 10 2023, Utrecht (The Netherlands) - When corona patients themselves measure the oxygen level in their blood at home, this is well applicable through the general practice. This was shown in a study conducted by UMC Utrecht during the pandemic. The study showed that patients could easily perform the oxygen measurement themselves at home, they felt safe doing so and the number of GP or hospital visits did not increase. The researchers believe that - by enabling care close to home - patients experience more control and that it contributes to relieving caregivers and keeping ...

Overweight boys more likely to be infertile men

2023-05-10

A new paper in the European Journal of Endocrinology, published by Oxford University Press, indicates that overweight boys tend to have lower testicular volume, putting them at risk for infertility in adulthood.

Infertility weighs on both the psychological health and the economic and social lives of people of childbearing age. Infertility affected 48 million couples in 2010. Although observers often overlook male infertility, researchers believe it is a factor contributing to couple infertility in about half of all cases. Yet ...

First structural analysis of highly reactive anionic Pt(0) complexes

2023-05-10

Anionic M0 complexes (M = group 10 metals) have attracted attention as active species for catalytic reactions; however, their molecular structures have very rarely been determined owing to their extremely high reactivity. Particularly, the structures of Pt0 complexes, which are expected to exhibit a high degree of reactivity, have not been determined, and their syntheses have been almost nonexistent.

Associate Professor Hajime Kameo, and Professor Hiroyuki Matsuzaka from the Osaka Metropolitan University Graduate School of Science and CNRS Senior Researcher Didier Bourissou (Paul Sabatier University - Toulouse III) elucidated the ...

Air pollution worsens movement disorder after stroke

2023-05-10

Air pollution has been shown to have a negative effect on the prognosis of ischemic stroke, or stroke caused by reduced blood flow to the brain, but the exact mechanism is unknown. A team of researchers recently conducted a study to determine whether or not increased inflammation of the brain, also known as neuroinflammation, is the main culprit.

The team published their findings in the February 16, 2023 issue of Particle and Fibre Toxicology.

Mice exposed intranasally to urban aerosols from Beijing, China, for one week demonstrated increased neuroinflammation ...

Most antidepressants prescribed for chronic pain lack reliable evidence of efficacy or safety, scientists warn

2023-05-10

Largest ever investigation into antidepressants used for chronic pain shows insufficient evidence to determine how effective or harmful they may be

Study reviewed commonly prescribed medications including amitriptyline, duloxetine, fluoxetine, citalopram, paroxetine, and sertraline

One third of people globally are living with long-term pain with many prescribed antidepressants to relieve symptoms

Most antidepressants used for chronic pain are being prescribed with “insufficient” evidence of their effectiveness, scientists have warned.

A major investigation into medications used to manage long-term pain found that ...

Dark clouds on the horizon

2023-05-10

Our industrialized society releases many and various pollutants into the world. Combustion in particular produces aerosol mass including black carbon. Although this only accounts for a few percent of aerosol particles, black carbon is especially problematic due to its ability to absorb heat and impede the heat reflection capabilities of surfaces such as snow. So, it’s essential to know how black carbon interacts with sunlight. Researchers have quantified the refractive index of black carbon to the most accurate degree yet which might impact climate models.

There are many factors driving climate change; some are very familiar, such ...

Scientists discover microbes in the Alps and Arctic that can digest plastic at low temperatures

2023-05-10

Finding, cultivating, and bioengineering organisms that can digest plastic not only aids in the removal of pollution, but is now also big business. Several microorganisms that can do this have already been found, but when their enzymes that make this possible are applied at an industrial scale, they typically only work at temperatures above 30°C. The heating required means that industrial applications remain costly to date, and aren’t carbon-neutral. But there is a possible solution to this problem: ...

Salt marshes protect the coast – but not where it is needed most

2023-05-10

Salt marshes provide multiple ecosystem services, one of those is protection of the coast against flooding. This is especially important in low-lying countries like the Netherlands. Scientists from the University of Groningen and the Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research (NIOZ), in collaboration with the local water authority, have monitored wave run-up during storms over a three-year period. The results, which were published in the Journal of Applied Ecology on 10 May, help the water authority to quantify the protective effect of salt marshes.

For three years, ecologist Beatriz Marin-Diaz always had one eye on the weather ...

New USC study shows immigrant adults with liver cancer have higher survival rates than those born in the US

2023-05-10

Immigrant adults with liver cancer in the United States have higher survival rates than people with the disease who were born in the U.S., according to new research from the USC Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the most common form of liver cancer, contributes to more than 27,000 deaths annually in the United States. Immigrants comprise a significant proportion of those diagnosed with HCC in the U.S. Research has shown that birthplace, also referred to as nativity, impacts incidence and risk factors for HCC, but little was known about its influence on survival after diagnosis.

The new study, just published in the Journal of the National ...

Physicists discover ‘stacked pancakes of liquid magnetism’

2023-05-10

HOUSTON – (May 10, 2023) – Physicists have discovered “stacked pancakes of liquid magnetism” that may account for the strange electronic behavior of some layered helical magnets.

The materials in the study are magnetic at cold temperatures and become nonmagnetic as they thaw. Experimental physicist Makariy Tanatar of Ames National Laboratory at Iowa State University noticed perplexing electronic behavior in layered helimagnetic crystals and brought the mystery to the attention of Rice theoretical physicist Andriy Nevidomskyy, who worked with Tanatar and former Rice graduate student Matthew Butcher to create a computational model that simulated the quantum states ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Alkali cation effects in electrochemical carbon dioxide reduction

Test platforms for charging wireless cars now fit on a bench

$3 million NIH grant funds national study of Medicare Advantage’s benefit expansion into social supports

Amplified Sciences achieves CAP accreditation for cutting-edge diagnostic lab

Fred Hutch announces 12 recipients of the annual Harold M. Weintraub Graduate Student Award

Native forest litter helps rebuild soil life in post-mining landscapes

Mountain soils in arid regions may emit more greenhouse gas as climate shifts, new study finds

Pairing biochar with other soil amendments could unlock stronger gains in soil health

Why do we get a skip in our step when we’re happy? Thank dopamine

UC Irvine scientists uncover cellular mechanism behind muscle repair

Platform to map living brain noninvasively takes next big step

Stress-testing the Cascadia Subduction Zone reveals variability that could impact how earthquakes spread

We may be underestimating the true carbon cost of northern wildfires

Blood test predicts which bladder cancer patients may safely skip surgery

Kennesaw State's Vijay Anand honored as National Academy of Inventors Senior Member

Recovery from whaling reveals the role of age in Humpback reproduction

Can the canny tick help prevent disease like MS and cancer?

Newcomer children show lower rates of emergency department use for non‑urgent conditions, study finds

Cognitive and neuropsychiatric function in former American football players

From trash to climate tech: rubber gloves find new life as carbon capturers materials

A step towards needed treatments for hantaviruses in new molecular map

Boys are more motivated, while girls are more compassionate?

Study identifies opposing roles for IL6 and IL6R in long-term mortality

AI accurately spots medical disorder from privacy-conscious hand images

Transient Pauli blocking for broadband ultrafast optical switching

Political polarization can spur CO2 emissions, stymie climate action

Researchers develop new strategy for improving inverted perovskite solar cells

Yes! The role of YAP and CTGF as potential therapeutic targets for preventing severe liver disease

Pancreatic cancer may begin hiding from the immune system earlier than we thought

Robotic wing inspired by nature delivers leap in underwater stability

[Press-News.org] New breathalyzer for disease sniffs out COVID in real-time, could be used to detect cancer, lung diseaseQuantum laser-based technology a big step forward toward using exhaled breath to diagnose illness