(Press-News.org)

A new study published in the journal Science by an international team finds that early human species adapted to mosaic landscapes and diverse food resources, which would have increased our ancestor’s resilience to past shifts in climate.

Our genus Homo evolved over the past 3 million years – a period of increasing warm/cold climate fluctuations. How early human species have adapted to the intensification of climate extremes, ice ages, and large-scale shifts in landscapes and vegetation remains elusive. Did our ancestors adjust to local environmental changes over time, or did they seek out more stable environments with diverse food resources? Was our human evolution influenced more by temporal changes in climate, or by the spatial character of the environment?

To test these fundamental hypotheses on human evolution and adaptation quantitively, the research team used a compilation of more than three thousand well-dated human fossil specimens and archeological sites, representing six different human species, in combination with realistic climate and vegetation model simulations, covering the past 3 million years. The scientists focused their analysis on biomes – geographic regions which are characterized by similar climates, plants, and animal communities (e.g., savannah, rainforest, or tundra).

“For the archeological and anthropological sites and corresponding ages, we extracted the local biome types from our climate-driven vegetation model. This revealed which biomes were favored by the extinct hominin species H. ergaster, H. habilis, H. erectus, H. heidelbergensis, and H. neanderthalensis and by our direct ancestors - H. sapiens.”, said Elke Zeller, Ph.D. student from the IBS Center for Climate Physics at Pusan National University, South Korea, and lead author of the study.

According to their analysis, the scientists found that earlier African groups preferred to live in open environments, such as grassland and dry shrubland. Migrating into Eurasia around 1.8 million years ago, hominins, such as H. erectus and later H. heidelbergensis and H. neanderthalensis developed higher tolerances to other biomes over time, including temperate and boreal forests. “To survive as forest-dwellers, these groups developed more advanced stone tools and likely also social skills”, said Prof. Pasquale Raia, from the Università di Napoli Federico II, Italy, co-author of the study. Eventually, H. sapiens emerged around 200,000 years ago in Africa, quickly becoming the master of all trades. Mobile, flexible, and competitive, our direct ancestors, unlike any other species before, survived in harsh environments such as deserts and tundra.

When further looking into the preferred landscape characteristics, the scientists found a significant clustering of early human occupation sites in regions with increased biome diversity. “What that means is that our human ancestors had a liking for mosaic landscapes, with a great variety of plant and animal resources in close proximity”, said Prof. Axel Timmermann, co-author of the study and Director of the IBS Center for Climate Physics in South Korea. The results indicate that ecosystem diversity played a key role in human evolution.

The authors demonstrated this preference for mosaic landscapes for the first time on continental scales and propose a new Diversity Selection Hypothesis: Homo species, and H. sapiens, in particular, were uniquely equipped to exploit heterogeneous biomes. “Our analysis shows the crucial importance of landscape and plant diversity as a selective element for humans and as a potential driver for socio-cultural developments” adds Elke Zeller. Elucidating how vegetation shifts have shaped human sustenance, the new Science study provides an unprecedented view into human prehistory and survival strategies.

The climate and vegetation model simulations, which cover the Earth’s history of the past 3 million years, were conducted on one of South Korea’s fastest science supercomputers named Aleph. “Supercomputing is now emerging as a key tool in evolutionary biology and anthropology”, said Axel Timmermann.

END

Scalloped hammerhead sharks hold their breath to keep their bodies warm during deep dives into cold water where they hunt prey such as deep sea squids. This discovery, published today in Science by University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa researchers, provides important new insights into the physiology and ecology of a species that serves as an important link between the deep and shallow water habitats.

“This was a complete surprise!” said Mark Royer, lead author and researcher with the Shark Research Group at the Hawai‘i Institute of Marine Biology (HIMB) in the UH Mānoa School of ...

From low-carb to intermittent fasting, surgery to Ozempic—people turn to a seemingly never-ending array of diets, procedures and drugs to lose weight. While it has been long understood that limiting the amount of food eaten can promote healthy aging in a wide range of animals, including humans, a new study from University of Michigan has revealed that the feeling of hunger itself may be enough to slow aging.

Previous research has demonstrated that even the taste and smell of food can reverse the beneficial, life-extending effects of diet restriction, even without its consumption.

These intriguing findings drove first author Kristy Weaver, Ph.D., principal investigator ...

When people leave their rural lives behind to seek their fortunes in the city or agriculture is no longer profitable, the lands they toiled on are often left unused. A new perspective piece in Science shows that these abandoned lands could be both an opportunity and a threat for biodiversity, and highlights why abandoned lands are critical in the assessment of global restoration and conservation targets.

The past 50 years have seen an increased exodus of populations from rural to urban areas. Today, 55% ...

Thanks to data from a magnified, multiply imaged supernova, a team led by University of Minnesota Twin Cities researchers has successfully used a first-of-its-kind technique to measure the expansion rate of the Universe. Their data provide insight into a longstanding debate in the field and could help scientists more accurately determine the Universe’s age and better understand the cosmos.

The work is divided into two papers, respectively published in Science, one of the world’s top peer-reviewed academic journals, and The Astrophysical Journal, a peer-reviewed scientific journal of astrophysics and astronomy.

In astronomy, there are two precise ...

Cancer of the penis is not a subject that comes up in conversation. When it does, one common response is, “I didn’t know you could get cancer there.” Not only is it not spoken about, but it is also rare, with fewer than one case per 100,000 men diagnosed in developed countries like the United States and the United Kingdom per year. That rarity has meant far fewer clinical trials have been developed and conducted to guide its treatment, and in most cases, only small numbers of patients have been included. Fortunately, researchers from both sides ...

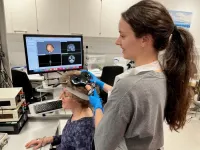

A UBC Okanagan researcher has been testing the effectiveness of a mobile app that encourages people living with a spinal cord injury—but can walk—to get active.

Dr. Sarah Lawrason, a researcher in the School of Health and Exercise Sciences, has focused her career on working with people who live with a spinal cord injury (SCI) but are ambulatory. She describes this population as an isolated, often misunderstood group of people because while they live with an SCI, they may not rely on a wheelchair all of the time for mobility.

“When people think of someone with an SCI, they picture a ...

TORONTO – May 11, 2023 – With funding from Canada’s Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC), Baycrest, the Kingston Indigenous Language Nest (KILN) and the University of Toronto have released a free online language course to learn the Indigenous language Ojibwe, also known as Anishinaabemowin.

The Ojibwe language is spoken in Indigenous communities around the Great Lakes in Canada and the US, but serious efforts are needed to ensure the long-term survival of the language.

“Due to the aging of people who ...

Experts from Newcastle University found the nervous system of people with post-Covid fatigue was underactive in three key areas. Fatigue is one of the most common symptoms of long Covid.

The breakthrough could lead to better treatment and tests to identify the condition and the team are already progressing the work having just started a trial. They have begun recruiting patients to test the effectiveness of a TENS machine – commonly used for pain relief in childbirth – to alleviate the fatigue in patients with long Covid.

Newcastle University ...

Into the Blue: Securing a Sustainable Future for Kelp Forests global synthesis report is the most comprehensive knowledge review on kelp to date, revealing the state of science on the world’s kelp forests and providing recommended actions to build the recovery of the world’s kelp forests.

Aiming to improve our understanding of the value of kelp forests and provide recommendations to protect and sustainably manage them, the report also provides a range of policy and management interventions and options that can be used to maintain these remarkable ecosystems into the future and to support the people and economies that have depended on them for generations.

Despite ...

LOS ANGELES — Two people regularly have a few alcoholic drinks daily. One develops liver disease. The other doesn’t.

What explains the different outcomes?

The answer may lie in a condition known as metabolic syndrome, a cluster of conditions that together raise the risk of coronary heart disease, diabetes, stroke and other serious health problems. This syndrome, characterized by symptoms such as abdominal fat, high blood pressure, high cholesterol and high blood sugar, affects more than one in three Americans.

A new ...