(Press-News.org) A study published by MBARI researchers and their collaborators today in Nature provides new insights about one of the earliest points in animal evolution that happened more than 700 million years ago.

For more than a century, scientists have been working to understand the pivotal moment when an ancient organism gave rise to the diverse array of animals in the world today. As technology and science have advanced, scientists have investigated two alternative hypotheses for which animals—sponges or comb jellies, also known as ctenophores—were most distantly related to all other animals. Identifying this outlier—known as the sibling group—has long eluded scientists.

In the new study, a team of researchers from MBARI, the University of Vienna, the University of California, Berkeley, and the University of California, Santa Cruz, mapped sets of genes that are always found together on a single chromosome, in everything from humans and hamsters to crabs and corals, to provide clear evidence that comb jellies are the sibling group to all other animals. Understanding the relationships among animals will help shape our thinking about how key features of animal anatomy, such as the nervous system or digestive tract, have evolved over time.

"We developed a new way to take one of the deepest glimpses possible into the origins of animal life. We’ve used genetics to travel back in time about one billion years to get the strongest evidence yet to answer a fundamental question about the earliest events in animal evolution," said Darrin Schultz, previously a graduate student researcher at MBARI and UC Santa Cruz and now a postdoctoral researcher in the Simakov group at the University of Vienna. “This finding will lay the foundation for the scientific community to begin to develop a better understanding of how animals—and humans—have evolved."

All of the genes in an animal are organized in sequences on chromosomes. The location of an individual gene sequence can change over time, but changes to the linkages between genes on a particular chromosome are rare and largely irreversible.

Until now, scientists have only looked at the similarities in the sequencing of individual genes to answer long-standing questions about the most ancient animal relationships.

Schultz and team examined the linkages between genes on specific chromosomes, which are deeply conserved throughout time. They identified patterns that exist in a variety of animals and mapped those linkages back to the earliest point in animal evolution. The team found strong evidence that comb jellies represent a unique lineage whose ancestors diverged before the common ancestor of all other animals.

The team compares this event to a genetic fork in the road of evolution that happened hundreds of millions of years ago. One lone single-celled organism, the ancestor of all animals, was traveling along that road with its two offspring. One child, which would evolve into comb jellies as we know them today, took one path. As it evolved, the genes on its chromosomes stayed in a specific order and did not change much. The other child, which would evolve into sponges and all other animals as we know them today, took the other path. Many of the genes on its chromosomes rearranged themselves and fused together. Because these rearrangements are irreversible and passed down generation to generation, they are detectable even today. By tracking these rearrangements, the team found clear-cut evidence that comb jellies, not sponges, are the sibling group to all other animals.

"The fingerprints of this ancient evolutionary event are still present in the genomes of animals hundreds of millions of years later," said Schultz. "This research helps strengthen the foundation of our understanding of the genetics of animal life. It gives us context for understanding what makes animals animals. This work will help us understand the basic functions we all share, like how they sense their surroundings, how they eat, and how they move."

Background

More than 700 million years ago, different groups of small organisms split off the tree of life to evolve along their own independent paths, becoming the animals we know today.

Researchers began working to understand the relationships between animals more than a century ago, and for most of this time period, they assumed that sponges split off the tree of life hundreds of millions of years ago making them the sibling group to all other animals.

However, 15 years ago, researchers were able to use new DNA-sequencing technologies to find the first evidence that ctenophores, not sponges, were the sibling group of all other animals. This research sparked a great effort by the scientific community to develop new ways to confirm the identity of the oldest branch of the animal family tree, but a definitive answer remained unclear.

While groups of animals have evolved hundreds of millions of years apart, a remarkably large number of genes remain linked to the same chromosomes across these vastly different groups. Over time, the sequence of genes on each chromosome may change, but the actual link to the chromosome remains the same, except for in rare circumstances. Researchers have historically compared the gene sequences that coded for key proteins to infer how groups of organisms are related to one another. However, they found that this technique did not give reliable answers about whether sponges or ctenophores were the sibling group of all other animals.

MBARI researchers used a novel technique to find new clues in the genomes of comb jellies and sponges.

First, Schultz and the team sequenced the genomes for the entire length of each chromosome for two comb jellies and two marine sponges as well as three single-celled close relatives of animals—a choanoflagellate, a filasterean amoeba, and an ichthyosporean—in order to create a more complete and organized picture of each one’s genes.

With the complete chromosome sequences in hand, MBARI researchers looked for patterns of linked genes to help answer the question of whether sponges or ctenophores are the most distant relative of all other animals.

Because links between genes and chromosome location change relatively slowly, these changes reveal how ancient genomes may have been arranged. Distinct, rare changes and conserved patterns can be used to unambiguously unite all descendant lineages. This can help resolve long-standing questions about animal relationships.

When they examined the chromosome-scale genome of comb jellies, they saw a grouping of genes that was very different from the patterns in other animals. Most importantly, they found patterns of genes that were shared between the ctenophores and three single-celled non-animals, whereas those patterns have been shuffled and mixed in all other animals, from sponges to sparrows.

Comparing specific patterns of linked genes allowed researchers to build a deeply-rooted tree of animal life and better establish the order in which branches split off from the main trunk.

The team uses two decks of cards—one blue and one yellow—as an analogy for how these gene linkages work.

The blue and yellow cards in each deck are separate and represent genes on distinct chromosomes. First, the two decks merge, representing chromosome fusion events. Then, shuffling the decks further is like swapping genes between chromosomes. Each shuffle yields an increasingly small chance that you could cut the deck and have all blue cards in one half and all yellow cards in the other. Likewise, following patterns of genes across the tree of animal life, there would be an increasingly small chance that gene linkages from ancestral organisms would be reproduced by chance in the furthest branches of the tree.

END

Genetic research offers new perspective on the early evolution of animals

Mapping gene linkages provides clear-cut evidence for comb jellies as sibling group to all other animals

2023-05-17

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Research spotlight: a conversational artificial intelligence program can generate credible medical information in response to common patient questions

2023-05-17

What was the question you set out to answer with this study?

ChatGPT, a new language processing tool driven by artificial intelligence (AI), provides conversational text responses to questions and can generate valuable information for enquiring individuals, but the quality of ChatGPT-generated answers to medical questions is currently unclear.

What Methods or Approach Did You Use?

We retrieved eight common questions and answers about colonoscopy from the publicly available webpages of three randomly-selected hospitals from the top-20 list of the US News & World Report Best Hospitals for Gastroenterology and Gastrointestinal Surgery.

We ...

How breast cancer arises

2023-05-17

In what may turn out to be a long-missing piece in the puzzle of breast cancer, Harvard Medical School researchers have identified the molecular sparkplug that ignites cases of the disease currently unexplained by the classical model of breast-cancer development.

A report on the team’s work is published May 17 in Nature.

“We have identified what we believe is the original molecular trigger that initiates a cascade culminating in breast tumor development in a subset of breast cancers that are driven by estrogen,” said study senior investigator Peter Park, professor of ...

Astronomers find potentially volcano-covered Earth-size world

2023-05-17

Cambridge, Mass. – Astronomers have discovered an Earth-size exoplanet, a world beyond the solar system, that may be carpeted with volcanoes and could potentially support life. Called LP 791-18 d, the planet could undergo volcanic outbursts as often as Jupiter’s moon Io, the most volcanically active body in the solar system.

The planet was first reported in Nature and the discovery was made possible in part due to ground-based observations made by the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian.

LP 791-18 d orbits a small red dwarf star about 90 light-years away in a southern constellation called Crater. The ...

Vigorous exercise not tied to increased risk of adverse events in rare heart condition

2023-05-17

Vigorous exercise does not appear to increase the risk of death or life-threatening arrhythmia for people with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), according to a study supported by the National Institutes of Health. HCM is a rare, inherited disorder that causes the heart muscle to become thick and enlarged and affects 1 in 500 people worldwide. It has been associated with sudden cardiac death in young athletes and other young people. However, the study, published in JAMA Cardiology, found that people with the disease who exercise vigorously are no more likely to die or experience severe cardiac events than those who exercised moderately ...

Climate change made record Asia humid heatwave at least 30 times more likely: attribution study

2023-05-17

Human-caused climate change made April’s record-breaking humid heatwave in Bangladesh, India, Laos and Thailand at least 30 times more likely, according to rapid attribution analysis by an international team of leading climate scientists as part of the World Weather Attribution group. The study also concludes that the high vulnerability in the region, which is one of the world’s heatwave hotpots, amplified the impacts.

In April, parts of south and southeast Asia experienced an intense heatwave, with record-breaking temperatures that passed 42ºC in Laos and 45°C in Thailand. The heat ...

Study finds link between deprived areas and number of children in care proceedings in England

2023-05-17

A strong link between the extent of deprivation of local authorities in England and their numbers of children going into the care system through the family courts has been uncovered by researchers at Lancaster University.

The study, available online and due to be published in July 2023 in the journal Children & Society, found that for every one unit increase in the standardized Office for National Statistics’ (ONS) English index of multiple area deprivation, the number of children in care proceedings in English family courts increased by around 70%.

The research team analysed data from the English Children and Family Court Advisory and Support Service ...

Call for papers: JMIR Dermatology special theme issue on teledermatology

2023-05-17

JMIR Dermatology—the official journal of the International Society of Teledermatology (ISTD)—and the journal’s guest editors welcome submissions to a special theme issue to coincide with the 10th ISTD World Congress held at the 23rd World Congress of Dermatology on July 4 to 7, 2023, in Singapore.

This theme issue will allow attendees of the ISTD World Congress to share their work with a wider audience by disseminating their work in a well-respected, peer-reviewed, open-access journal.

Teledermatology has been increasingly gaining recognition as a means of delivering dermatological ...

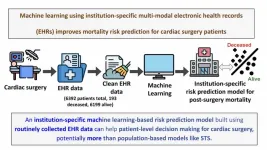

Researchers show that a machine learning model can improve mortality risk prediction for cardiac surgery patients

2023-05-17

A machine learning-based model that enables medical institutions to predict the mortality risk for individual cardiac surgery patients has been developed by a Mount Sinai research team, providing a significant performance advantage over current population-derived models.

The new data-driven algorithm, built on troves of electronic health records (EHR), is the first institution-specific model for assessing a cardiac patient’s risk prior to surgery, thus allowing health care providers to pursue the best course of action for that individual. The team’s work was described in a study published in The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery ...

Machine learning lets researchers see beyond the spectrum

2023-05-17

Tokyo, Japan – Organic chemistry, the study of carbon-based molecules, underlies not only the science of living organisms, but is critical for many current and future technologies, such as organic light-emitting diode (OLED) displays. Understanding the electronic structure of a material’s molecules is key to predicting the material’s chemical properties.

In a study recently published by researchers at the Institute of Industrial Science, The University of Tokyo, a machine-learning algorithm was developed to predict the density ...

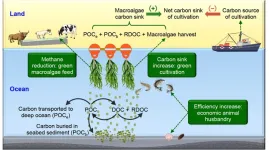

The predicted average annual net carbon sink of Gracilaria cultivation in China from 2021 to 2030 may double that of the last ten years

2023-05-17

A marine research team led by Professor YAN Qingyun has proposed a method to assess the net carbon sink of marine macroalgae (Gracilaria) cultivation. Then, they calculated the net carbon sink of Gracilaria cultivation in China based on the yield of annual cultivated Gracilaria in the last ten years. Also, the net carbon sink trend of Gracilaria cultivation in the next ten years was predicted by the autoregressive integrated moving average model (ARIMA). Finally, they explored the potential carbon sink increase and methane reduction related to Gracilaria cultivation in China through a scenario analysis.

Their results suggested that the net carbon sink ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

A promising potential therapeutic strategy for Rett syndrome

How time changes impact public sentiment in the U.S.

Analysis of charred food in pot reveals that prehistoric Europeans had surprisingly complex cuisines

As a whole, LGB+ workers in the NHS do not experience pay gaps compared to their heterosexual colleagues

How cocaine rewires the brain to drive relapse

Mosquito monitoring through sound - implications for AI species recognition

UCLA researchers engineer CAR-T cells to target hard-to-treat solid tumors

New study reveals asynchronous land–ocean responses to ancient ocean anoxia

Ctenophore research points to earlier origins of brain-like structures

Tibet ASγ experiment sheds new light on cosmic rays acceleration and propagation in Milky Way

AI-based liquid biopsy may detect liver fibrosis, cirrhosis and chronic disease signals

Hope for Rett syndrome: New research may unlock treatment pathway for rare disorder with no cure

How some skills become second nature

SFU study sheds light on clotting risks for female astronauts

UC Irvine chemists shed light on how age-related cataracts may begin

Machine learning reveals Raman signatures of liquid-like ion conduction in solid electrolytes

Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia researchers emphasize benefits and risks of generative AI at different stages of childhood development

Why conversation is more like a dance than an exchange of words

With Evo 2, AI can model and design the genetic code for all domains of life

Discovery of why only some early tumors survive could help catch and treat cancer at very earliest stages

Study reveals how gut bacteria and diet can reprogram fat to burn more energy

Mayo Clinic researchers link Parkinson's-related protein to faster Alzheimer's progression in women

Trends in metabolic and bariatric surgery use during the GLP-1 receptor agonist era

Loneliness, anxiety symptoms, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation in the all of us dataset

A decision-support system to personalize antidepressant treatment in major depressive disorder

Thunderstorms don’t just appear out of thin air - scientists' key finding to improve forecasting

Automated CT scan analysis could fast-track clinical assessments

New UNC Charlotte study reveals how just three molecules can launch gene-silencing condensates, organizing the epigenome and controlling stem cell differentiation

Oldest known bony fish fossils uncover early vertebrate evolution

High‑performance all‑solid‑state magnesium-air rechargeable battery enabled by metal-free nanoporous graphene

[Press-News.org] Genetic research offers new perspective on the early evolution of animalsMapping gene linkages provides clear-cut evidence for comb jellies as sibling group to all other animals