(Press-News.org) A team of researchers have confirmed that 107-million-year-old pterosaur bones discovered more than 30 years ago are the oldest of their kind ever found in Australia, providing a rare glimpse into the life of these powerful, flying reptiles that lived among the dinosaurs.

Published in the journal Historical Biology and completed in collaboration with Museums Victoria, the research analysed a partial pelvis bone and a small wing bone discovered by a team led by Museums Victoria Research Institute’s Senior Curator of Vertebrate Palaeontology Dr Tom Rich and Professor Pat Vickers-Rich at Dinosaur Cove in Victoria, Australia in the late 1980s.

The team found the bones belonged to two different pterosaur individuals. The partial pelvis bone belonged to a pterosaur with a wingspan exceeding two metres, and the small wing bone belonged to a juvenile pterosaur — the first ever reported in Australia.

Lead researcher and PhD student Adele Pentland, from Curtin’s School of Earth and Planetary Sciences, said pterosaurs — which were close cousins of the dinosaurs — were winged reptiles that soared through the skies during the Mesozoic Era.

“During the Cretaceous Period (145–66 million years ago), Australia was further south than it is today, and the state of Victoria was within the polar circle — covered in darkness for weeks on end during the winter. Despite these seasonally harsh conditions, it is clear that pterosaurs found a way to survive and thrive,” Ms Pentland said.

“Pterosaurs are rare worldwide, and only a few remains have been discovered at what were high palaeolatitude locations, such as Victoria, so these bones give us a better idea as to where pterosaurs lived and how big they were.

“By analysing these bones, we have also been able to confirm the existence of the first ever Australian juvenile pterosaur, which resided in the Victorian forests around 107 million years ago.”

Ms Pentland said that although the bones provide important insights about pterosaurs, little is known about whether they bred in these harsh polar conditions.

“It will only be a matter of time until we are able to determine whether pterosaurs migrated north during the harsh winters to breed, or whether they adapted to polar conditions. Finding the answer to this question will help researchers better understand these mysterious flying reptiles,” Ms Pentland said.

Dr Tom Rich, from Museums Victoria Research Institute, said it was wonderful to see the fruits of research coming out of the hard work of Dinosaur Cove which was completed decades ago.

“These two fossils were the outcome of a labour-intensive effort by more than 100 volunteers over a decade,” Dr Rich said.

“That effort involved excavating more than 60 metres of tunnel where the two fossils were found in a seaside cliff at Dinosaur Cove.”

The research was co-authored by researchers from Curtin’s School of Earth and Planetary Sciences, the Australian Age of Dinosaurs Museum of Natural History, Monash University, and Museums Victoria Research Institute.

The full paper is titled, ‘Oldest pterosaur remains from Australia: evidence from the Lower Cretaceous (lower Albian) Eumeralla Formation of Victoria,’ and can be found online here.

END

Study finds 107-million-year-old pterosaur bones are oldest in Australia

2023-05-30

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Quarter-ton marsupial roamed long distances across Australia’s arid interior

2023-05-30

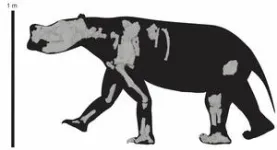

One of Australia’s first long-distance walkers has been described after Flinders University palaeontologists used advanced 3D scans and other technology to take a new look at the partial remains of a 3.5 million year old marsupial from central Australia.

They have named a new genus of diprotodontid Ambulator, meaning walker or wanderer, because the locomotory adaptations of the legs and feet of this quarter-tonne animal would have made it well suited to roam long distances in search of food and ...

Source-shifting metastructures composed of only one resin for location camouflaging

2023-05-30

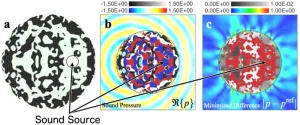

The field of transformation optics has flourished over the past decade, allowing scientists to design metamaterial-based structures that shape and guide the flow of light. One of the most dazzling inventions potentially unlocked by transformation optics is the invisibility cloak — a theoretical fabric that bends incoming light away from the wearer, rendering them invisible. Interestingly, such illusions are not restricted to the manipulations of light alone.

Many of the techniques used in transformation optics have been applied to sound waves, giving rise to the parallel field of transformation acoustics. In fact, researchers ...

Code-switching in intercultural communication: Japanese vs Chinese point of view

2023-05-30

When people communicate, speakers and listeners use information shared by both the parties, which is referred to as ‘context.’ It is believed that there are cultural differences in the degree of reliance on this context, with Westerners having a low-context culture, i.e., they speak more directly, and Easterners having a high-context culture, i.e., they are subtle and speak less directly.

Although Chinese are assumed to be in a high-context culture, Yamashina (2018) found that Chinese people are viewed as more direct speakers i.e., low-context cultural communicators ...

Trials will investigate if rock dust can combat climate crisis

2023-05-30

Scientists at the UK Centre for Ecology & Hydrology (UKCEH) are trialling an innovative approach to mitigating climate change and boosting crop yield in mid-Wales. Adding crushed rock dust to farmland has the potential to remove and lock up large amounts of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

In the first trial of Enhanced Rock Weathering on upland grasslands in the world, UKCEH scientists have applied 56 tonnes of finely ground basalt rock from quarries to three hectares of farmland in Plynlimon, Powys, this month and are repeating this at the same time next year.

The basalt rock dust particles, which are less than 2mm in size, absorb and store carbon at faster rates ...

Women with a first normal weight offspring and a small second offspring have increased risk of cardiovascular mortality

2023-05-30

A new study from the University of Bergen reveals that including offspring birthweight information from women’s subsequent births, is helpful in identifying a woman's long-term risk of dying from cardiovascular causes.

Knowledge of the association between offspring birthweight and long-term maternal cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality is often based on first-born infants without considering women’s consecutive births.

“These possible relations are also less closely studied among women with term deliveries”, ...

ENDO 2023 press conferences to highlight emerging technology and diabetes research

2023-05-30

CHICAGO—Researchers will delve into the latest research in diabetes, obesity, reproductive health and other aspects of endocrinology during the Endocrine Society’s ENDO 2023 news conferences June 15-18.

The Society also will share its Hormones and Aging Scientific Statement publicly for the first time during a news conference on Friday, June 16. Reporters will have an opportunity to hear from members of the writing group that drafted the statement on the research landscape.

Other press conferences will feature select abstracts that are being presented at ENDO 2023, the Endocrine Society’s annual meeting. The event is being held at McCormick Place in Chicago, Ill. ...

New tool may help spot “invisible” brain damage in college athletes

2023-05-30

An artificial intelligence computer program that processes magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can accurately identify changes in brain structure that result from repeated head injury, a new study in student athletes shows. These variations have not been captured by other traditional medical images such as computerized tomography (CT) scans. The new technology, researchers say, may help design new diagnostic tools to better understand subtle brain injuries that accumulate over time.

Experts have long known about potential risks of concussion among young athletes, particularly for those who play high-contact sports such as football, hockey, and soccer. Evidence is now mounting ...

The next generation of solar energy collectors could be rocks

2023-05-30

The next generation of sustainable energy technology might be built from some low-tech materials: rocks and the sun. Using a new approach known as concentrated solar power, heat from the sun is stored then used to dry foods or create electricity. A team reporting in ACS Omega has found that certain soapstone and granite samples from Tanzania are well suited for storing this solar heat, featuring high energy densities and stability even at high temperatures.

Energy is often stored in large batteries when not needed, but these can be expensive and require lots of resources to manufacture. A lower-tech alternative ...

Hidden in plain sight: Windshield washer fluid is an unexpected emission source

2023-05-30

Exhaust fumes probably come to mind when considering vehicle emissions, but they aren’t the only source of pollutants released by a daily commute. In a recent ACS’ Environmental Science & Technology study, researchers report that alcohols in windshield washer fluid account for a larger fraction of real-world vehicle emissions than previous estimates have suggested. Notably, the levels of these non-fuel-derived gases will likely remain unchanged, even as more drivers transition from gas-powered ...

Humans evolved to walk with an extra spring in our step

2023-05-30

A new study has shown that humans may have evolved a spring-like arch to help us walk on two feet. Researchers studying the evolution of bipedal walking have long assumed that the raised arch of the foot helps us walk by acting as a lever which propels the body forward. But a global team of scientists have now found that the recoil of the flexible arch repositions the ankle upright for more effective walking. The effects in running are greater, which suggests that the ability to run efficiently could have been a selective pressure for a flexible arch that made walking more efficient too. This discovery could even help doctors improve ...