(Press-News.org) Every so often, life on Earth steps onto a nearly empty playing field and faces a spectacular opportunity. Something major changes—in the atmosphere or in the oceans, or in the organisms themselves —and the existing species begin to branch out into a brand-new world. Scientists are fascinated by this process, because it’s a unique look into evolution at pivotal moments in the history of life.

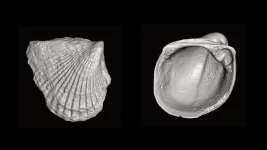

A new study led by scientists with the University of Chicago examined how bivalves—the group that includes clams, mussels, scallops, and oysters—evolved among many others in the period of rapid evolution known as the Cambrian Explosion. The team found that though many other lineages burst into action and quickly evolved a wide variety of forms and functions, the bivalves lagged behind, perhaps because they took too long to evolve a particular adaptation they needed to flourish.

The study has implications for how we understand evolution and the impact of extinctions, the scientists said.

Shell and high water

A little more than 500 million years ago, the diversity of life on Earth suddenly exploded. Known as the Cambrian Explosion, this dramatic episode saw the emergence of many forms of life that persist today.

Among these were the bivalves—hard-twin-shelled organisms that live on the seafloor. A group of researchers decided to catalogue the rise of the bivalves to see how they fared in a nearly empty sea with a brand-new body design.

The research team, including Stewart Edie (PhD’18) with the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, Katie Collins with the U.K.’s Natural History Museum, and Sharon Zhou, a fourth-year undergraduate student at UChicago, went through the fossil record and painstakingly examined each known fossil species to get a picture of how the bivalves evolved new forms and ways of living—such as burrowing into the seafloor sediment versus attaching themselves to rocks. “For example, you can look at the shape of the shell and tell if they are likely digging into the seafloor sediment, because they become long and thin for burrowing,” explained Zhou.

They pieced together a comprehensive picture of the bivalves’ evolution—and were surprised.

“You might think that they would take immediate advantage of this new body design and go on to fame and biological fortune,” said David Jablonski, the William R. Kenan Jr. Distinguished Service Professor of Geophysical Sciences at UChicago and co-corresponding author on the paper. “But they didn’t.”

Instead, the bivalves branched out slowly compared to other groups that originated at the time. “It’s kind of amazing they made it through at all,” said Jablonski. “Even after they got their act together and began to diversify about 40 million years in, they never showed a true explosion in species or ecologies.”

One thing they wanted to check was whether this could be a false impression caused by some gap in the fossil record. Collins explained that fossils from that era are difficult to find in the first place—many rocks have since been metamorphized into other rock types—and also hard to identify where they do exist.

However, Edie and Zhou ran a series of tests and computer simulations and found this was unlikely to have affected the results: “We’d need a really extreme simulation to change the pattern we see in the rocks,” said Edie. “It’s much more likely that this slow start was the real story.”

It’s not clear why the bivalves lagged, but one possibility is that they hadn’t yet evolved a key organ that allowed them to take off: an enlarged gill to filter out plankton from water, as so many bivalves do today. By the time they came up with this adaptation, the seafloor was much more crowded. “If you show up early to the dance floor, you can do whatever you want, but if you show up late, it restricts the range of moves,” Jablonski said.

But the bivalves do survive and even thrive today, despite their lag. “It tells us there’s more than one pathway to success, even when you are starting at the very beginning of multicellular life,” said Jablonski.

Scientists are particularly interested in cataloguing these accounts of evolution, because they can suggest how life adapts and radiates in the wake of major disruptions or extinctions. The researchers plan to look at bivalves’ response to extinctions over time and see if similar patterns emerge.

“For all kinds of reasons, we want to understand what it means to repopulate after an extinction—for example, what could happen as a result of the major extinction we are undergoing right now,” said Jablonski.

The study was also a learning experience for Zhou, who is an undergraduate at the University of Chicago.

Zhou intended to major in math, but was hooked on evolutionary biology after she took a course to fulfill UChicago’s Core requirements in the sciences. She spent several years working in Jablonski’s lab, and now plans to attend graduate school in the subject.

“How life happens on earth—to me, that is one of the greatest mysteries we can try to solve,” said Zhou.

UChicago postdoctoral researcher Nicholas Crouch was also a co-author on the paper.

END

The clams that fell behind, and what they can tell us about evolution and extinction

UChicago scientists study how bivalves evolved after the Cambrian Explosion

2023-05-31

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Medical school does not equip new doctors for the real working world, junior doctor warns

2023-05-31

Clinician burnout and overwork are known to adversely affect patient safety and junior doctors may be particularly vulnerable, research suggests.

The UK is facing a crisis in recruitment and retention in medicine, with a recent survey by the British Medical Association reporting that 4 in 10 junior doctors will quit their roles as soon as they find another job.

Considering the immense pressure doctors are under, with their decisions having the potential to shape the course of patients’ illnesses and even their lives, is a balanced and happy life as a doctor still possible?

In a new book released today titled The Bleep Test, junior doctor Luke Austen has combined ...

Unique “bawdy bard” act discovered, revealing 15th-century roots of British comedy

2023-05-31

University of Cambridge media release

UNDER STRICT EMBARGO UNTIL 00:01AM (UK TIME) ON WEDNESDAY 31ST MAY 2023

An unprecedented record of medieval live comedy performance has been identified in a 15th-century manuscript. Raucous texts – mocking kings, priests and peasants; encouraging audiences to get drunk; and shocking them with slapstick – shed new light on Britain’s famous sense of humour and the role played by minstrels in medieval society.

The texts contain the earliest recorded use of ‘red herring’ in English, extremely rare forms of medieval literature, as well as a ...

Saved from extinction, Southern California’s Channel Island Foxes now face new threat to survival

2023-05-31

Tiny foxes — each no bigger than a five-pound housecat — inhabiting the Channel Islands off the coast of Southern California were saved from extinction in 2016. However, new research reveals that the foxes now face a different threat to their survival.

Suzanne Edmands, professor of biological sciences at USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences, and Nicole Adams, who earned her PhD from USC Dornsife in 2019, found that the foxes’ genetic diversity has decreased over time, possibly jeopardizing their survival ...

Genetic change increased bird flu severity during U.S. spread

2023-05-31

(MEMPHIS, Tenn. – May 29, 2023) St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital scientists discovered how the current epizootic H5N1 avian influenza virus (bird flu) gained new genes and greater virulence as it spread west. Researchers showed that the avian virus could severely infect the brains of mammalian research models, a notable departure from previous related strains of the virus. The researchers genetically traced the virus’ expansion across the continent and its establishment in wild waterfowl populations to understand what makes it so different. The study was recently published in Nature Communications.

“We ...

New Jersey Health Foundation awards grants to Kessler Foundation to advance research in brain and spinal cord stimulation methods

2023-05-30

East Hanover, NJ – May 30, 2023 – Annually, New Jersey Health Foundation (NJHF) invites researchers to submit applications for grants aimed at supporting pilot research projects that exhibit promising potential. These grants serve as opportunities for scientists to utilize their initial findings to secure further funding and progress their research. This year, NJHF granted awards to two Kessler Foundation scientists to conduct studies that expand research in upper extremity exercise after stroke ...

Extracting a clean fuel from water

2023-05-30

A plentiful supply of clean energy is lurking in plain sight. It is the hydrogen we can extract from water (H2O) using renewable energy. Scientists are seeking low-cost methods for producing clean hydrogen from water to replace fossil fuels, as part of the quest to combat climate change.

Hydrogen can power vehicles while emitting nothing but water. Hydrogen is also an important chemical for many industrial processes, most notably in steel making and ammonia production. Using cleaner hydrogen is highly desirable in those industries.

“By using ...

NJIT researchers awarded $4.6m to unlock mysteries of solar eruptions

2023-05-30

A New Jersey Institute of Technology research team led by physics professor Wenda Cao at the university’s Center for Solar Terrestrial Research (CSTR) has been awarded a $4.64 million National Science Foundation grant to continue leading explorations of the Sun’s explosive activity at Big Bear Solar Observatory (BBSO).

The grant marks the largest project that the Solar-Terrestrial Research Program under NSF’s Division of Atmospheric and Geospace Sciences (AGS) supports, extending five more years of baseline funding for all science, instrumentation and education activities at BBSO, located at California’s Big Bear Lake.

The ...

Extended lymph node removal does not benefit patients with clinically localized muscle-invasive bladder cancer

2023-05-30

An extended lymphadenectomy – removal of additional lymph nodes beyond the extent of the standard procedure – in patients undergoing radical cystectomy (removal of bladder and nearby tissues) because of clinically localized muscle-invasive bladder cancer provides no patient benefit as measured by disease-free survival or overall survival times. It does, however, increase the risk of adverse events (side effects) and post-surgical death.

These primary results from the phase 3 SWOG S1011 clinical ...

Study finds sex education tool improves reproductive health knowledge among adolescent girls

2023-05-30

HUNTINGTON, W.Va. – A Marshall University study found that a virtual sex education tool improved reproductive health knowledge scores and measures of self-efficacy among adolescent girls.

The findings, published last month in Sex Education, a leading international journal on sex, sexuality and relationships in education, found that sexual health knowledge scores on a validated scale increased among participants, along with improved measures of self-efficacy regarding birth control, healthy relationships and sexually transmitted infection (STI) prevention. Notably, ...

No-till revolution could stop Midwest topsoil loss in its tracks

2023-05-30

American Geophysical Union

25 May 2023

AGU Release No. 22

For Immediate Release

This press release and accompanying multimedia are available online at: https://news.agu.org/press-release/no-till-revolution-could-stop-midwest-topsoil-loss-in-its-tracks/

No-till revolution could stop Midwest topsoil loss in its tracks

If Midwestern farms all adopted low-intensity tilling practices or stopped tilling entirely, the erosion of critical topsoil could decrease by 95% in the next 100 years, new study finds

AGU press contact:

Rebecca ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

ESC launches guidelines for patients to empower women with cardiovascular disease to make informed pregnancy health decisions

Towards tailor-made heat expansion-free materials for precision technology

New research delves into the potential for AI to improve radiology workflows and healthcare delivery

Rice selected to lead US Space Force Strategic Technology Institute 4

A new clue to how the body detects physical force

Climate projections warn 20% of Colombia’s cocoa-growing areas could be lost by 2050, but adaptation options remain

New poll: American Heart Association most trusted public health source after personal physician

New ethanol-assisted catalyst design dramatically improves low-temperature nitrogen oxide removal

New review highlights overlooked role of soil erosion in the global nitrogen cycle

Biochar type shapes how water moves through phosphorus rich vegetable soils

Why does the body deem some foods safe and others unsafe?

Report examines cancer care access for Native patients

New book examines how COVID-19 crisis entrenched inequality for women around the world

Evolved robots are born to run and refuse to die

Study finds shared genetic roots of MS across diverse ancestries

Endocrine Society elects Wu as 2027-2028 President

Broad pay ranges in job postings linked to fewer female applicants

How to make magnets act like graphene

The hidden cost of ‘bullshit’ corporate speak

Greaux Healthy Day declared in Lake Charles: Pennington Biomedical’s Greaux Healthy Initiative highlights childhood obesity challenge in SWLA

Into the heart of a dynamical neutron star

The weight of stress: Helping parents may protect children from obesity

Cost of physical therapy varies widely from state-to-state

Material previously thought to be quantum is actually new, nonquantum state of matter

Employment of people with disabilities declines in february

Peter WT Pisters, MD, honored with Charles M. Balch, MD, Distinguished Service Award from Society of Surgical Oncology

Rare pancreatic tumor case suggests distinctive calcification patterns in solid pseudopapillary neoplasms

Tubulin prevents toxic protein clumps in the brain, fighting back neurodegeneration

Less trippy, more therapeutic ‘magic mushrooms’

Concrete as a carbon sink

[Press-News.org] The clams that fell behind, and what they can tell us about evolution and extinctionUChicago scientists study how bivalves evolved after the Cambrian Explosion