(Press-News.org) CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — Asian colobines, also known as leaf-eating monkeys, have been on the planet for about 10 million years. Their ancestors crossed land bridges, dispersed across continents, survived the expansion and contraction of ice sheets and learned to live in tropical, temperate and colder climes.

A new study reported in the journal Science finds parallels between Asian colobines’ social, environmental and genetic evolution, revealing for the first time that colobines living in colder regions experienced genetic changes and alterations to their ancient social structure that likely enhanced their ability to survive.

“Virtually all primates are social and live in social groups,” said study co-author Paul A. Garber, a professor emeritus of anthropology at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and an expert on primate biology, evolution and conservation. “But the groups differ in size and cohesiveness. There are those that live in units of two or three individuals and others living in communities of up to 1,000 individuals.”

Asian colobines have evolved a variety of social structures. However, genomic studies suggest that the harem unit of organization, which consists of one male with two or more females and their offspring, was the ancestral norm for Asian colobines, Garber said. The males are intolerant of other males and will fight to protect their territories. In some species, females remain in their natal group. In others, both males and females leave to join or form a new harem.

Over time, more complex societies formed. Among a group of Asian colobines known as “odd-nosed monkeys,” for example, two genera “still form harems, but they’re not territorial,” Garber said. “This means their group territories can overlap and there are times they may come together to forage, rest and travel.” One branch of these odd-nosed monkeys, the “snub-nosed monkeys” form what is referred to as a multilevel or modular society in which several harems remain together year-round and form a large and cohesive breeding band.

The largest such society the team recorded included about 400 individuals. In the case of the golden snub-nosed monkeys, breeding between individuals belonging to different harems was common, occurring about 50% of the time.

The researchers wanted to examine how the interplay of environment, genes and behaviors like territoriality and cooperation allowed Asian colobines to survive in such varied habitats.

“The team used extremely diverse data sets, many of which we generated ourselves,” Garber said. “These include ecological and paleogeological data, the fossil record, and behavioral and genomic data.”

By overlaying social structure and habitat data, the team found that Asian colobine groups that inhabit colder areas – many of them at high elevations – also tend to form larger and more complex societies made up of harems that coordinate their daily activities and often cooperate with one another. The changes in social structure over time corresponded with genetic changes, the researchers found. The most socially complex multilevel societies also evolved changes in genes regulating cold-related energy metabolism and neurohormones that are known to play a critical role in social bonding.

Several factors contributed to the colobines’ social evolution into larger, more cooperative societies, Garber said.

“Because these primates are long-lived and individuals may remain in the same band for periods of years and even decades, you have the opportunity for high levels of reciprocal cooperation,” he said.

Habitat also played a role, he said. Smaller groups in tropical areas can afford to be territorial because food is more predictable, and they can sustain themselves in a fairly restricted area. However, life at higher altitudes is more challenging.

Black-and-white snub-nosed monkeys in some parts of China, for example, live at elevations up to about 13,500 feet.

“These are low-oxygen environments,” Garber said. “The coldest temperatures at night drop below zero. For a primate, that’s cold.”

Historically, predators of snub-nosed monkeys were large mammals like snow leopards, tigers and bears. Predation risk was likely lowered by the cooperative efforts of males from multiple harems, Garber said. In addition, plant resources consumed by snub-nosed monkeys are more spread out, making their extremely large territories – which can extend up to 6-8 square miles (15-20 square kilometers) – harder to defend by small groups.

In addition to changes in genes that code for lipid metabolism and adaptations associated with cold stress, colobines living at high elevations also saw genetic changes that bolstered hormones – such as oxytocin and dopamine – that are known to play a role in maternal behavior and social relationships.

“The snub-nosed monkeys seem to have a longer mother-infant bond, which probably increased infant survival in cold environments,” Garber said. “Oxytocin is an important neurohormone in all social bonding. We think it promoted social affiliation, cohesion and cooperation among adults as well.”

Each of these adaptive changes appears to have bolstered affiliation between harems, allowing Asian colobines to form larger multilevel societies when local conditions made it necessary for them to cooperate to survive, the researchers report.

The National Science Foundation of China, the Chinese Academy of Sciences and the Department of Science and Technology of Shaanxi Province supported this research.

Corresponding authors of the study are Xiao-Guang Qi, of Northwest University, Xi’an, China; Cyril C. Grueter, of the University of Western Australia, Perth; Dongdong Wu, of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming, China; and Baoguo Li, of Northwest University, China.

Garber also is affiliated with the Program in Ecology, Evolution and Conservation Biology, the Center for Global Studies and the Center for Latin American and Caribbean Studies at the U. of I.

Editor’s notes:

To reach Paul A. Garber, email p-garber@illinois.edu.

Upon publication, the paper “Adaptations to a cold climate promoted social evolution in Asian colobine primates” is available online and from the U. of I. News Bureau.

DOI: 10.1126/science.abl8621

END

Embargoed until 1-Jun-2023 14:00 ET (1-Jun-2023 18:00 GMT/UTC)

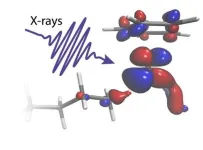

The use of short flashes of X-ray light brings scientists one big step closer toward developing better catalysts to transform the greenhouse gas methane into a less harmful chemical. The result, published in the journal Science, reveals for the first time how carbon-hydrogen bonds of alkanes break and how the catalyst works in this reaction.

Methane, one of the most potent greenhouse gases, is being released into the atmosphere at an increasing rate by livestock farming as well as the continuing unfreezing of permafrost. Transforming methane and longer-chain alkanes into less harmful and in fact useful chemicals ...

For the first time ever, scientists have uncovered evidence that a species’ long-term adaptation to living in an extremely cold climate has led to the evolution of social behaviours including extended care by mothers, increased infant survival and the ability to live in large complex multilevel societies.

The new study, published today in the journal Science, was led by researchers from Northwest University in China and a team including the University of Bristol (UK) and the University of Western Australia, ...

Article URL: https://journals.plos.org/ploscompbiol/article?id=10.1371/journal.pcbi.1011087

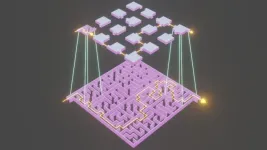

Article Title: Humans decompose tasks by trading off utility and computational cost

Author Countries: USA

Funding: This research was supported by John Templeton Foundation grant 61454 awarded to TLG and NDD (https://www.templeton.org/), U.S. Air Force Office of Scientific Research grant FA 9550-18-1-0077 awarded to TLG (https://www.afrl.af.mil/AFOSR/), and U.S. Army Research Office grant ARO W911NF-16-1-0474 awarded to NDD (https://www.arl.army.mil/who-we-are/directorates/aro/). ...

Baboons (Papio) are found across the continent of Africa, from the west to the east and all the way south. They have doglike noses, impressive teeth and thick fur that ranges widely in color between the six species, which are olive, yellow, chacma, Kinda, Guinea and hamadryas. Their habitats vary from savannas and bushlands to tropical forests and mountains. Chacma baboons, the largest at up to 100 pounds, are even found in the Kalahari Desert, while the neighboring Kinda baboons, the smallest at around 30 pounds, stay near water. Most live in large troops with dozens or hundreds of members. While most baboons ...

Co-led by Guojie Zhang from Centre for Evolutionary & Organismal Biology at Zhejiang University, Dong-Dong Wu at Kunming Institute of Zoology, Xiao-Guang Qi at Northwest University, Li Yu at Yunnan University, Mikkel Heide Schierup at Aarhus University, and Yang Zhou at BGI-Research, the Primate Genome Consortium reported a series of publications from its first phase program which includes high quality reference genomes from 50 primate species of which 27 were sequenced for the first time. These studies provide new insights on the speciation process, genomic diversity, social evolution, ...

HOUSTON – (June 1, 2023) – A new investigation led by researchers at Baylor College of Medicine’s Human Genome Sequencing Center, the Institute of Evolutionary Biology and Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona, Spain, and Illumina, Inc. analyzed the genomes of 233 nonhuman primate species and revealed key features of primate evolution, human disease and biodiversity conservation. The findings are published in a series of studies in a special issue of the journal Science.

The Primate Genome Project generated the most complete ...

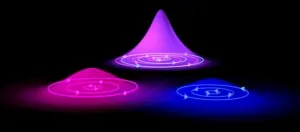

Within superconductors little tornadoes of electrons, known as quantum vortices, can occur which have important implications in superconducting applications such as quantum sensors. Now a new kind of superconducting vortex has been found, an international team of researchers reports.

Egor Babaev, professor at KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm, says the study revises the prevailing understanding of how electronic flow can occur in superconductors, based on work about quantum vortices that was recognized in the 2003 Nobel Prize award. The ...

The University of Miami has been chosen as one of the newest members of the esteemed Association of American Universities (AAU), a distinguished national organization of leading research universities founded in 1900.

The invitation to join the prestigious organization—considered the gold standard in American higher education—comes as the University’s research and sponsored program expenditures totaled more than $413 million in fiscal year 2022, demonstrating a critical focus to address the world’s most complex issues.

“There are special moments in the life of a university that not only reward our hard work but, more importantly, ...

Dr. Robert A. Harrington, a cardiologist and the Arthur L. Bloomfield Professor of Medicine and chair of the Department of Medicine at Stanford University, has been named the Stephen and Suzanne Weiss Dean of Weill Cornell Medicine and provost for medical affairs of Cornell University.

The appointment was approved by the Cornell Board of Trustees and the Weill Cornell Medicine Board of Fellows. Harrington - also a member of the National Academy of Medicine - will begin his new position on Sept. 12.

A past president of the American Heart Association (AHA), ...

Laszlo Horvath, an early career physicist at the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL) stationed at General Atomics in San Diego, is the winner of the 2022 Károly Simonyi Memorial Plaque from the Hungarian Nuclear Society. Established in 2007, the plaque “recognizes Hungarian researchers and engineers with outstanding achievements in the field of fusion plasma physics and technology.”

Horvath learned he had won the Simonyi Memorial Plaque not long ...