The dwarf cuttlefish is a master of camouflage. In a matter of milliseconds, the animal can shift both its skin pattern and texture to dynamically blend in with its surroundings. Camouflage is visually driven, and like its squid and octopus cousins, the cuttlefish controls its skin color with its brain. Neurons inside the brain project their axons all the way to the skin, where they control hundreds of thousands of cellular pixels (chromatophores) to achieve color change.

When a cuttlefish camouflages, it reproduces what it sees on its skin. To achieve this, the cuttlefish must transform its visual input into a neural representation in the brain, and then recreate an analog of that representation on its skin. The lab of Richard Axel, MD, wants to understand how the cuttlefish achieves this astonishing feat. Understanding the way in which the visual world is represented in the brain–whether of a cephalopod or a human–and how that representation leads to thoughts and behaviors, are among the most compelling issues in neuroscience.

To uncover the neural basis of cuttlefish camouflage, members of the Axel lab need to record the activity of neurons from relevant regions of the cuttlefish brain. To extract the most scientific value from those recordings, however, they also need a map of the brain, which has not been available. So the team embarked on a project to build a neuroanatomical atlas of the dwarf cuttlefish brain. Their research paper describing the project appears today online in Current Biology, with a corresponding website, Cuttlebase.org.

“One of my favorite approaches for learning about the brain is to study creatures that are highly specialized in particular behaviors or tasks, such as bats that use echolocation to navigate, or birds that use impressive spatial memory to recall the locations of hidden food items,” said Tessa G. Montague, PhD, first author on the paper and a postdoctoral fellow in the lab of Richard Axel, MD, also an author of the paper.

“We hope and believe that our brain atlas will help the community learn more about the mechanisms cuttlefish use to express themselves through their skin, and that this may give us insight into how any brain is capable of representing information,” said Dr. Montague.

It took a tight and devoted collaboration of experts in neuroscience, tissue imaging, computer programming, anatomy and web design to build Cuttlebase. For the underlying foundation of the brain atlas, the team scanned the bodies and brains of four male and four female cuttlefish using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), a diagnostic mainstay for physicians. A deep-learning algorithm, a type of artificial intelligence, helped tease out the animals’ brains from their surrounding tissue, in the scan data.

Co-author Sabrina Gjerswold-Selleck, who recently completed a Master’s degree at Columbia University and now works for Neuralink, said the team had a running start with the research because of related work she had done in coauthor Jia Guo’s group at Columbia with MRI scans of mice.

“We had developed a deep-learning approach that was able to separate the brain-related data in each MRI scan from the data linked to other tissue types in these scans,” said Gjerswold-Selleck. “We were surprised how well we were able to adapt the technique.”

Next, by comparing the MRI scans with just a handful of labeled brain images from the 1960s, the researchers had to determine the boundaries of each dwarf cuttlefish brain lobe. This was a monumental effort of data analysis by six of the coauthors who devoted hundreds of hours during the pandemic to delineating the eight cuttlefish data sets.

This resulted in hundreds of grayscale images with outlines of the brain regions analogous to, say, the outlines of states and counties in a multi-page atlas of the United States. To upgrade their cuttlefish brain atlas so that it offers cellular resolution – equivalent to a detailed atlas that shows all of the roads, hills, lakes and rivers of the states – the researchers turned to histological techniques, which reveal the microscopic structure of tissue. This required the biologists in the team to meticulously section the cuttlefish brains and then stain each with colorful chemical labels that mark the locations of brain cells and parts, including neurons, glial cells and axons.

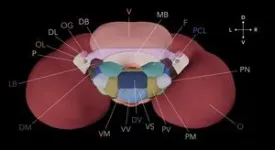

One of many views in the webtool Cuttlebase of the multi-lobe brain of dwarf cuttlefish Sepia bandensis (Credit: Cuttlefish team/Axis Lab/Zuckerman Institute)

Finally, after completing the histological atlas and annotating the eight cuttlefish MRI scans, the researchers merged the eight brains into a single atlas. In total, they identified 32 lobes in the dwarf cuttlefish, most of which they could connect with specific biological functions and behaviors, on account of classic studies from half a century ago. The two largest lobes, the optic lobes, process visual input from the animal’s mesmerizing eyes, for example. The motor neurons in the chromatophore lobes orchestrate the color-changing mechanisms in the skin. A vertical lobe has been implicated in learning and memory.

Although this analysis of cuttlefish data is itself of consequence, “the main purpose of the paper is to report the visualization and research tool, Cuttlebase, and to make it all freely available and easily accessible to everyone,” said Dr. Montague.

With intuitive ease, users can summon histological sections that specify different brain regions and nerves; a rotatable and zoomable 3D model of the brain; and a 3D model of the cuttlefish’s 26 organs, including its three hearts, ink sac, beak and nerves that carry signals between the brain and its eight arms. All of the data in Cuttlebase are available to other researchers to build upon in their labs. Explanations of the brain lobes and other user-friendly features provide learning resources for non-experts.

Coauthors Sukanya Aneja and Dana Elkis (the team’s web engineer and web designer, respectively) of the Interactive Telecommunications Program at New York University, who are also members of the Cuttlebase team, played lead roles in developing the website.

“We had a lot of back and forth about how to translate everything we had into a web-based experience that would be appealing to both scientists and nonscientists,” said Aneja.

“We needed to combine videos, images, the 3D template brain, illustrations, charts and diagrams,” noted Elkis.

Coauthor Isabelle Rieth, a graduate student in Northwestern University’s Interdepartmental Neuroscience Program and a former member of the Cuttlebase team, brought in additional design skills to transform what otherwise would have been a black-and-white web experience into one bursting with colors that help clarify what users are seeing.

As challenging and labor-intensive as the project has been for the collaborators, they cannot help but remain enamored by the cuttlefish they work with and are learning about.

“The cuttlefish are mesmerizing to watch,” said Dr. Montague. “When they’re camouflaging or communicating with each other, they’re effectively revealing to you on their skin what they see and how they feel.”

###

The paper, titled “A brain atlas for the camouflaging dwarf cuttlefish, Sepia bandensis,” was published online in Current Biology on June 20, 2023. Its full list of authors includes: Tessa G. Montague, Isabelle J. Rieth, Sabrina Gjerswold-Selleck, Daniella Garcia-Rosales, Sukanya Aneja, Dana Elkis, Nanyan Zhu, Sabrina Kentis, Frederick A. Rubino, Adriana Nemes, Katherine Wang, Luke A. Hammond, Roselis Emiliano, Rebecca A. Ober, Jia Guo, Richard Axel.

END