(Press-News.org) All around us, insects are speaking to each other: jockeying for mates, searching for food, and trying to avoid becoming someone else’s next meal. Some of this communication is easy to spot—like the flashes of fireflies on a summer night or a screaming chorus of cicadas in the afternoon—but many of the most sophisticated conversations are challenging to observe, occurring through an exchange of chemical scents.

Understanding chemical communication could be the key to finding new, more effective ways to protect crops or ward off biting insects that can transmit diseases. Researchers at SRI International, in collaboration with scientists at Virginia Tech and Rutgers University, have devised a method for identifying sections of genetic code that make the chemicals that insects use to communicate. Their work, published recently in Protein Science, provides a roadmap for understanding how chemical communication evolved and is the first step in deciphering what specific insects are saying.

“Pest control is a longer-term goal here, particularly in agriculture,” said Paul O’Maille, the program director of biocomplexity sciences at SRI and corresponding author on the paper. “We need to decode this language, be able to intercept it, and maybe redirect it in intelligent ways.”

Insects communicate with a class of chemicals called terpenes, which vaporize easily and spread through the air, covering a large area and potentially reaching lots of other insects. But until recently, researchers thought that insects weren’t able to produce them on their own. It was generally assumed that insects acquired terpenes from their environment, collecting them from food they ate or hosting microbes that could produce them.

“Just in the last handful of years, my collaborators and others discovered that insects actually have genes to encode for enzymes called terpene synthases, and that is the mouthpiece of this communication form,” O’Maille said. Terpene synthases are what allow a species to create their own terpenes. “That opened up a new world for us.”

With the realization that some insects had the ability to create terpenes written into their genetic code, the researchers set out to devise a method of finding similar genes in other species. O’Maille, who has been studying terpenes in plants for a couple decades, was able to break down the chemistry needed to make a terpene and determine which genes would have to be tweaked to make that happen. He identified several motifs—patterns in the genetic code—that are specific to terpene synthases.

“We’ve basically put together a ruleset for understanding the natural history of how these terpene synthases came to be, and that leads to a heuristic, or a method, to predict whether a gene is a terpene synthase or not,” O’Maille said. “Using that heuristic, we see that there are loads of these terpene synthase genes across different insects—they’re quite prevalent.”

The researchers have already identified several hundred potential terpene synthase genes by applying their method to available genetic sequences of insects. The species they’ve looked at represent only eight of the 29 insect orders so far, but their data indicates that terpene-based chemical communication evolved independently multiple times.

By providing this blueprint, the researchers hope to help fellow scientists verify the identity of terpene synthases in many more insects and start the process of understanding how those terpenes are being used. And once we speak the language, we can try to use it our advantage. If we know, for example, which chemicals are attractive to insects that prey on important crops, we might be able to sow clusters of decoy plants that produce those chemicals and draw insects away.

“Our ability to decode that conversation gives us more options,” O’Maille said.

O’Maille also highlights that the methods used in this paper can be applied to more than just insects. The same techniques O’Maille and his colleagues used to predict which sections of the genome codes for terpene synthases could be applied to other enzymes in other species.

“Right now, we can sequence genomes at-will, but we can’t interpret the genome very well,” O’Maille said. “Our work provides a roadmap for developing heuristics for other classes of enzymes to have more accurate predictions of the functions of genes.”

END

SRI seeks to learn how insects speak through smells

Understanding chemical communication among insects could help find new ways to protect crops or ward off biting insects that can transmit diseases.

2023-06-20

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Cuttlefish brain atlas first of its kind

2023-06-20

NEW YORK, NY — Anything with three hearts, blue blood and skin that can change colors like a display in Times Square is likely to turn heads. Meet Sepia bandensis, known more descriptively as the camouflaging dwarf cuttlefish. Over the past three years, a team led by neuroscientists at Columbia’s Zuckerman that includes data experts and web designers has put together a brain atlas of this captivating cephalopod: a neuroanatomical roadmap depicting for the first time the brain’s overall 32-lobed structure as well its cellular organization.

The ...

Climate action plans mobilize limited urban change, researchers report

2023-06-20

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Fifth Assessment Report (AR5), released just prior to an international climate convention in 2015, explicitly stated that human-caused greenhouse gas emissions were the highest in history, with clear and widespread impacts on the climate system. Since then, hundreds of cities across the world have published their own climate action plans (CAPs), detailing how their urban areas will handle climate change. How do the plans stack up against one another and against the recommended ...

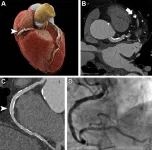

Photon-counting CT noninvasively detects heart disease in high-risk patients

2023-06-20

OAK BROOK, Ill. – New ultra-high-resolution CT technology enables excellent image quality and accurate diagnosis of coronary artery disease in high-risk patients, a potentially significant benefit for people previously ineligible for noninvasive screening, according to a study published in Radiology, a journal of the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA).

Coronary artery disease is the most common form of heart disease. Coronary CT angiography (CCTA) is highly effective for ruling out coronary artery disease ...

Self-driving revolution hampered by a lack of accurate simulations of human behavior

2023-06-20

Self-driving revolution hampered by a lack of accurate simulations of human behaviour

Algorithms that accurately reflect the behaviour of road users - vital for the safe roll out of driverless vehicles - are still not available, warn scientists.

They say there is “formidable complexity” in developing software that can predict the way people behave and interact on the roads, be they pedestrians, motorists or bike riders.

To improve the modelling, a research team led by Professor Gustav Markkula from the Institute of Transport Studies ...

Toxic emissions from wildland-urban interface fires

2023-06-20

Fires in the wildland-urban interface (WUI) emit more toxic smoke than wildfires burning in natural vegetation, due to the chemicals in the structures, vehicles, and other manufactured goods that burn in fires in areas of human habitation. Amara Holder and colleagues surveyed the literature on emissions from urban fuels, finding 28 experimental studies that reported emission factors—emissions per unit of fuel burned—for various items, such as home furnishings, consumer electronics, and vehicle ...

Electing progressives with patriotism, family, and tradition

2023-06-20

Economically progressive candidates may fare better in US elections when delivering their message in terms of “binding values” such as patriotism, family, and respect for tradition, according to a study. Although large majorities of Americans favor increasing economic equality in the United States, candidates who promote policies intended to reduce economic inequality, such as raising the minimum wage or increasing access to health care, often fare poorly at the ballot box. One reason for their under-performance may ...

Locating executive functions in fish brains

2023-06-20

The telencephalon is the part of the brain responsible for executive functions in fish, according to an experimental study. Zegni Triki and colleagues used guppies (Poecilia reticulata) that had been selected over five generations to have smaller or larger telencephalons, resulting in a 10% size difference between “up selected” and “down selected” lines of fish. Total brain size was not significantly affected. The authors then presented 48 male fifth-generation fish from both lines with tests of cognitive flexibility, inhibitory control, and working memory—the three commonly accepted components ...

Modeling human behavior for autonomous vehicles

2023-06-20

A model of human psychology could help self-driving cars interact with human drivers on the road, according to a study. Gustav Markkula and colleagues combined several computational psychological models into one master-model to simulate pedestrians attempting to cross a busy road and the human drivers on that road. The goal of the model was to capture the underlying cognitive mechanisms responsible for observed behavior. Computational models of Bayesian perception, theory of mind, behavioral game theory, long-term valuation of ...

Cholesterol lures in coronavirus

2023-06-20

A recent study unveiled the doorway that SARS-CoV2 uses to slip inside cells undetected.

SARS-CoV-2 uses the receptor angiotensin-converting enzyme 2, or ACE2, to infect human cells. However, this receptor alone does not paint a complete picture of how the virus enters cells. ACE2 is like a doorknob; when SARS-CoV-2 grabs it and maneuvers it precisely, this allows the virus to open a doorway to the cell’s interworking and step inside. However, the identity of the door eluded scientists.

Scott Hansen, an associate ...

2023 Warren Alpert Foundation Prize honors pioneer in computational biology

2023-06-20

The 2023 Warren Alpert Foundation Prize has been awarded to scientist David J. Lipman for his visionary work in the conception, design, and implementation of computational tools, databases, and infrastructure that transformed the way biological information is analyzed and accessed freely and rapidly around the world.

The $500,000 award is bestowed by The Warren Alpert Foundation in recognition of work that has improved the understanding, prevention, treatment, or cure of human disease. The prize is administered by Harvard Medical School.

Lipman will be honored at a scientific symposium on Oct. 11, 2023, hosted by HMS. For further information, visit ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Ochsner MD Anderson uses groundbreaking TIL therapy to treat advanced melanoma in adults

A heatshield for ‘never-wet’ surfaces: Rice engineering team repels even near-boiling water with low-cost, scalable coating

Skills from being a birder may change—and benefit—your brain

Waterloo researchers turning plastic waste into vinegar

Measuring the expansion of the universe with cosmic fireworks

How horses whinny: Whistling while singing

US newborn hepatitis B virus vaccination rates

When influencers raise a glass, young viewers want to join them

Exposure to alcohol-related social media content and desire to drink among young adults

Access to dialysis facilities in socioeconomically advantaged and disadvantaged communities

Dietary patterns and indicators of cognitive function

New study shows dry powder inhalers can improve patient outcomes and lower environmental impact

Plant hormone therapy could improve global food security

A new Johns Hopkins Medicine study finds sex and menopause-based differences in presentation of early Lyme disease

Students run ‘bee hotels’ across Canada - DNA reveals who’s checking in

SwRI grows capacity to support manufacture of antidotes to combat nerve agent, pesticide exposure in the U.S.

University of Miami business technology department ranked No. 1 in the nation for research productivity

Researchers build ultra-efficient optical sensors shrinking light to a chip

Why laws named after tragedies win public support

Missing geomagnetic reversals in the geomagnetic reversal history

EPA criminal sanctions align with a county’s wealth, not pollution

“Instead of humans, robots”: fully automated catalyst testing technology developed

Lehigh and Rice universities partner with global industry leaders to revolutionize catastrophe modeling

Engineers sharpen gene-editing tools to target cystic fibrosis

Pets can help older adults’ health & well-being, but may strain budgets too

First evidence of WHO ‘critical priority’ fungal pathogen becoming more deadly when co-infected with tuberculosis

World-first safety guide for public use of AI health chatbots

Women may face heart attack risk with a lower plaque level than men

Proximity to nuclear power plants associated with increased cancer mortality

Women’s risk of major cardiac events emerges at lower coronary plaque burden compared to men

[Press-News.org] SRI seeks to learn how insects speak through smellsUnderstanding chemical communication among insects could help find new ways to protect crops or ward off biting insects that can transmit diseases.