(Press-News.org) Researchers from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History have identified the oldest decisive evidence of humans’ close evolutionary relatives butchering and likely eating one another.

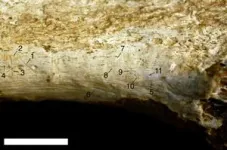

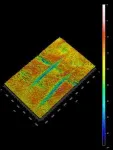

In a new study published today, June 26, in Scientific Reports, National Museum of Natural History paleoanthropologist Briana Pobiner and her co-authors describe nine cut marks on a 1.45 million-year-old left shin bone from a relative of Homo sapiens found in northern Kenya. Analysis of 3D models of the fossil’s surface revealed that the cut marks were dead ringers for the damage inflicted by stone tools. This is the oldest instance of this behavior known with a high degree of confidence and specificity.

“The information we have tells us that hominins were likely eating other hominins at least 1.45 million years ago,” Pobiner said. “There are numerous other examples of species from the human evolutionary tree consuming each other for nutrition, but this fossil suggests that our species’ relatives were eating each other to survive further into the past than we recognized.”

Pobiner first encountered the fossilized tibia, or shin bone, in the collections of the National Museums of Kenya’s Nairobi National Museum while looking for clues about which prehistoric predators might have been hunting and eating humans’ ancient relatives. With a handheld magnifying lens, Pobiner pored over the tibia looking for bite marks from extinct beasts when she instead noticed what immediately looked to her like evidence of butchery.

To figure out if what she was seeing on the surface of this fossil were indeed cut marks, Pobiner sent molds of the cuts—made with the same material dentists use to create impressions of teeth—to co-author Michael Pante of Colorado State University. She provided Pante with no details about what he was being sent, simply asking him to analyze the marks on the molds and tell her what made them. Pante created 3D scans of the molds and compared the shape of the marks to a database of 898 individual tooth, butchery and trample marks created through controlled experiments.

The analysis positively identified nine of the 11 marks as clear matches for the type of damage inflicted by stone tools. The other two marks were likely bite marks from a big cat, with a lion being the closest match. According to Pobiner, the bite marks could have come from one of the three different types of saber-tooth cats prowling the landscape at the time the owner of this shin bone was alive.

By themselves, the cut marks do not prove that the human relative who inflicted them also made a meal out of the leg, but Pobiner said this seems to be the most likely scenario. She explained that the cut marks are located where a calf muscle would have attached to the bone—a good place to cut if the goal is to remove a chunk of flesh. The cut marks are also all oriented the same way, such that a hand wielding a stone tool could have made them all in succession without changing grip or adjusting the angle of attack.

“These cut marks look very similar to what I’ve seen on animal fossils that were being processed for consumption,” Pobiner said. “It seems most likely that the meat from this leg was eaten and that it was eaten for nutrition as opposed to for a ritual.”

While this case may appear to be cannibalism to a casual observer, Pobiner said there is not enough evidence to make that determination because cannibalism requires that the eater and the eaten hail from the same species.

The fossil shin bone was initially identified as Australopithecus boisei and then in 1990 as Homo erectus, but today, experts agree that there is not enough information to assign the specimen to a particular species of hominin. The use of stone tools also does not narrow down which species might have been doing the cutting. Recent research from Rick Potts, the National Museum of Natural History’s Peter Buck Chair of Human Origins, further called into question the once-common assumption that only one genus, Homo, made and used stone tools.

So, this fossil could be a trace of prehistoric cannibalism, but it is also possible this was a case of one species chowing down on its evolutionary cousin.

None of the stone-tool cut marks overlap with the two bite marks, which makes it hard to infer anything about the order of events that took place. For instance, a big cat may have scavenged the remains after hominins removed most of the meat from the leg bone. It is equally possible that a big cat killed an unlucky hominin and then was chased off or scurried away before opportunistic hominins took over the kill.

One other fossil—a skull first found in South Africa in 1976—has previously sparked debate about the earliest known case of human relatives butchering each other. Estimates for the age of this skull range from 1.5 to 2.6 million years old. Apart from its uncertain age, two studies that have examined the fossil (the first published in 2000 and the latter in 2018) disagree about the origin of marks just below the skull’s right cheek bone. One contends the marks resulted from stone tools wielded by hominin relatives and the other asserts that they were formed through contact with sharp-edged stone blocks found lying against the skull. Further, even if ancient hominins produced the marks, it is not clear whether they were butchering each other for food, given the lack of large muscle groups on the skull.

To resolve the issue of whether the fossil tibia she and her colleagues studied is indeed the oldest cut-marked hominin fossil, Pobiner said she would love to reexamine the skull from South Africa, which is claimed to have cut marks using the same techniques observed in the present study.

She also said this new shocking finding is proof of the value of museum collections.

“You can make some pretty amazing discoveries by going back into museum collections and taking a second look at fossils,” Pobiner said. “Not everyone sees everything the first time around. It takes a community of scientists coming in with different questions and techniques to keep expanding our knowledge of the world.”

This research was supported by funding from the Smithsonian, the Peter Buck Fund for Human Origins Research and Colorado State University.

# # #

END

Scientists led by Sabine Taschner-Mandl, PhD, St. Anna Children's Cancer Research Institute, and Nikolaus Fortelny, PhD, Paris Lodron University of Salzburg, are the first to analyze bone marrow metastases from childhood tumors of the nervous system using modern single-cell sequencing analysis. It turns out that cancer cells prevent cells in their environment from fighting the tumor – a process that could be reversed with medication. The findings were published in the renowned journal Nature Communications.

Neuroblastoma is the most ...

For many patients with hypertension—an elevated blood pressure that can lead to stroke or heart attack—medication keeps the condition at bay. But what happens when medication that physicians usually prescribe doesn’t work? Known as apparent resistant hypertension (aRH), this form of high blood pressure requires more medication and medical management.

Novel research from investigators in the Smidt Heart Institute at Cedars-Sinai, published today in the peer-reviewed journal Hypertension, found that aRH prevalence was lower in ...

New controlled trial research documents that Progesterone (micronized, oral) is effective at decreasing night sweats and improving sleep in perimenopausal women who have menstruated in the last 1-year. Perimenopausal women most want treatment for these two symptoms.

Current guidelines prescribe Menopausal Hormone Therapy (MHT) for disturbing hot flushes/flashes or night sweats (vasomotor symptoms, VMS) in all women younger than 60 years.

“This guideline assumes that hormone levels and symptoms are the same in the early years of ...

Study reveals some distinctions between Black women in the US and the French Caribbean but increasing trends for aggressive forms in both regions.

Compared with white women, Black women have elevated risks of being diagnosed with advanced uterine cancer—also known as endometrial cancer—and of developing aggressive tumors. Researchers recently compared the incidence and trends for endometrial cancer, both overall and by subtype, between African descent women in Florida and women in the French Caribbean—specifically, the islands of Martinique and Guadeloupe. The findings are published by Wiley online ...

MIAMI, FLORIDA (EMBARGOED UNTIL 3:01 AM ET Monday, June 26, 2023) – Current evidence indicates Black women in the U.S. are at greater risk of developing advanced uterine cancer, also known as endometrial cancer, and of developing its more aggressive form – non-endometroid cancer – than white women.

But research to date has mostly studied Black women as a homogenous group, and there is limited data about specific African-descent subpopulations worldwide. That is until now.

A new study by researchers with Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center and the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine compared both the overall incidence and trends for endometrial ...

Orlando, Fla., June 26, 2023 – Facing persistent cases of hospital-onset Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) during the pandemic, the infection prevention and control (IPC) team at Children’s Hospital New Orleans developed an inexpensive nasal decolonization regimen previously used only in their adult patients that decreased rates of MRSA by 50 percent. Their results are being presented at the Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology’s (APIC’s) Annual Conference in Orlando Florida, June 26-28.

Without a lot of scientific literature on nasal decolonization in the pediatric population to guide them, Infection Preventionist ...

Neurosurgical Infections Drop More Than 80% in Two Years at Pittsburgh Hospital

Readmissions, patient satisfaction scores improve through infection preventionist-led, multidisciplinary collaboration

Orlando, Fla. June 26, 2023 – When excess surgical site infections (SSIs) were detected among neurosurgery patients at University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC) Mercy in 2019, infection preventionist Katie Palladino, MPH, CPH, CIC, partnered with a hospital neurosurgeon on a multidisciplinary quality and process improvement initiative that ...

To address health inequities that Indigenous and racialized patients can experience, collect data on racial and Indigenous identity at health card application and renewal, suggests a group of authors in CMAJ (Canadian Medical Association Journal) https://www.cmaj.ca/lookup/doi/10.1503/cmaj.221587.

"Although race is a social construct that uses perceived physical differences to create and maintain power differentials and the existence of discrete racial groups has not been shown to have any biological basis, perceived race influences how people are treated by individuals and institutions," ...

Every €1 invested in the Global Biodiversity Information Facility provides €3 in direct benefits to users and up to €12 in societal benefits, according to the the first economic valuation of GBIF's network, infrastructure and services. This finding is one of several insights outlined in the report, Economic valuation and assessment of the impact of the GBIF network, prepared and published by Deloitte Access Economics.

The Deloitte team of economists applied multiple analytical methods to produce this estimate, comparing and combining the results to quantify the total ...

About The Study: Exposure to posthospitalization home-delivered meals was associated with lower 30-day rehospitalization and mortality; randomized clinical trials are needed to confirm these findings.

Authors: Huong Q. Nguyen, Ph.D., R.N., of the Southern California Permanente Medical Group in Pasadena, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamahealthforum.2023.1678)

Editor’s Note: Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions ...