(Press-News.org) **EMBARGOED TILL TUESDAY, JUNE 27, AT 2 P.M. ET**

For the first two weeks of life, mice with a hereditary form of deafness have nearly normal neural activity in the auditory system, according to a new study by Johns Hopkins Medicine scientists. Their previous studies indicate that this early auditory activity — before the onset of hearing — provides a kind of training to prepare the brain to process sound when hearing begins.

The findings are published June 27 in PLOS Biology.

Mutations in Gjb2 cause more than a quarter of all hereditary forms of hearing loss at birth in people, according to some estimates. The connexin 26 protein coded by the gene is in a family of proteins known as GAP junctions, because these proteins span the tiny gap between cells and form a kind of tube that connects two cells to trade ions, metabolites and other molecules that communicate or maintain an equilibrium.

This unexpected finding, according to investigators, suggests a molecular mechanism for the observation that people with this hereditary mutation respond well to cochlear implants, the electronic devices that are designed to mimic sound conduction in the inner ear and can improve hearing in those with severe hearing loss. According to the National Institutes of Health, about 118,100 cochlear implants were implanted in adults and 65,000 in children between December 2019 and March 2021.

The connexin 26 protein in the cochlea, the spiral-like structure in the inner ear, is highly enriched in supportive cells, which, like their name implies, provide structural and nutritional help to surrounding hair cells and auditory neurons.

Previous studies have shown that, without connexin 26, the cochlea fails to develop its normal shape and is incapable of amplifying sound-induced vibrations necessary for efficient sound detection. Despite this disruption to the cochlear structure, this research shows the cochlea is still capable of producing the “spontaneous” activity needed to shape brain development.

“Supportive cells are extremely important for tissues and organs,” says neuroscientist Dwight Bergles, Ph.D., the Diana Sylvestre and Charles Homcy Professor at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. “The new study shows how critical they are for training the auditory system and getting it ready to process sound.”

For the study, Bergles and Calvin Kersbergen, an M.D./Ph.D. candidate in Johns Hopkins’ Medical Scientist Training Program, created a mouse model that lacked connexin 26 specifically in supportive cells in the cochlea.

By using external electrodes to measure electrical responses in the auditory nerve in response to tones or clicks, they found that mice lacking connexin 26 only in supportive cells of the cochlea were, indeed, deaf, demonstrating the crucial role of these intercellular channels in hearing.

However, Bergles and Kersbergen wondered if this change in supportive cells and shape of the cochlea would also disrupt spontaneous activity in younger mice, less than 2 weeks old, before their ear canal opens.

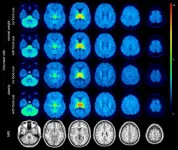

The researchers found that mice without connexin 26 still exhibit bursts of electrical activity in auditory neurons at nearly the same levels as young mice with intact connexin 26. Further investigation revealed that spontaneous activity in supportive cells was able to activate sensory hair cells in the inner ear, leading to normal neuronal activity in sound-processing areas of the brain.

“Even in the absence of connexin 26, we still find robust spontaneous activity in the cochlea in these young mice,” says Bergles.

Bergles says there is now evidence that the role of supportive cells in this early period is to “train” the auditory system to respond to sound at certain frequencies. Since the ear canal isn’t open yet, supportive cells generate their own activity spontaneously to stimulate the mechanically sensitive hair cells in the fluid-filled cochlea.

“It’s as if the cochlea is producing its own ‘sounds’ at this stage of development,” Bergles says. “This practice may help the auditory neurons and circuits in the brain mature before the ear canal opens.”

“It’s like a baseball player in a batting cage, learning the basics of their swing and preparing to face the unpredictability of a real pitcher,” says Bergles.

Finally, the researchers found that spontaneous activity in supportive cells of deaf mice halts once the ear canal opens. At the same time, because the mice can’t process sound, their auditory neurons actually increase their sensitivity to sound.

This hypersensitivity to sound is similar to the phenomenon of hyperacusis, in which normal levels of sound can be painful. In humans, this hearing loss-induced hypersensitivity can also lead to constant ringing of the ears, called tinnitus.

Bergles says the research also suggests a molecular mechanism for why people with this hereditary mutation who receive cochlear implants early on tend to do better than those who receive them later.

“Spontaneous activity in supportive cells in the cochlea may provide the molecular evidence for empirical data showing better outcomes among people who have cochlear implants placed earlier in life,” says Bergles.

The research team plans to study whether they can tap into the spontaneous activity pathway in supportive cells to treat tinnitus and other auditory conditions.

Scientists Travis Babola and Patrick Kanold also contributed to this research.

Funding was provided by the National Institutes of Health (F30DC018711, F32DC019842, U19NS107464, R01DC009607, R01DC008860, P30NS050274).

END

Deaf mice have nearly normal inner ear function until ear canal opens

Findings support placement of cochlear implants early in life

2023-06-27

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Chemists are on the hunt for the other 99 percent

2023-06-27

The universe is awash in billions of possible chemicals. But even with a bevy of high-tech instruments, scientists have determined the chemical structures of just a small fraction of those compounds, maybe 1 percent.

Scientists at the Department of Energy’s Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) are taking aim at the other 99 percent, creating new ways to learn more about a vast sea of unknown compounds. There may be cures for disease, new approaches for tackling climate change, or new chemical or biological threats lurking in the chemical universe.

The work is part of an initiative known as m/q or “m over q”—shorthand ...

Easier access to opioid painkillers may reduce opioid-related deaths

2023-06-27

Increasing access to prescription opioid painkillers may reduce opioid overdose deaths in the United States, according to a Rutgers study.

“When access to prescription opioids is heavily restricted, people will seek out opioids that are unregulated,” said Grant Victor, an assistant professor in the Rutgers School of Social Work and lead author of the study published in the Journal of Substance Use and Addiction Treatment. “The opposite may also be true; our findings suggest that restoring easier access to opioid pain medications may protect against fatal overdoses.”

America’s opioid crisis has ...

Fear of being exploited is stagnating our progress in science

2023-06-27

Science is a collaborative effort. What we know today would have never been, had it not been generations of scientists reusing and building on the work of their predecessors.

However, in modern times, academia has become increasingly competitive and indeed rather hostile to the individual researchers. This is especially true for early-career researchers yet to secure tenure and build a name in their fields. Nowadays, scholars are left to compete with each other for citations of their published work, awards and funding.

So, understandably, many scientists have grown unwilling ...

New findings on hepatitis C immunity could inform future vaccine development

2023-06-27

A new USC study that zeros in on the workings of individual T cells targeting the hepatitis C virus (HCV) has revealed insights that could assist in the development of an effective vaccine.

Every year, hepatitis and related illnesses kill more than one million people around the world. If unaddressed, those deaths are expected to rise—and even outnumber deaths caused collectively by HIV, tuberculosis and malaria by 2040.

For that reason, the World Health Organization and other leading groups have pledged to work toward eliminating viral hepatitis by 2030. While there are vaccines for two of the three most common ...

Cooperation between muscle and liver circadian clocks, key to controlling glucose metabolism

2023-06-27

Collaborative work by teams at the Department of Medicine and Life Sciences (MELIS) at Pompeu Fabra University (UPF), University of California, Irvine (UCI), and the Institute for Research in Biomedicine (IRB Barcelona) has shown that interplay between circadian clocks in liver and skeletal muscle controls glucose metabolism. The findings reveal that local clock function in each tissue is not enough for whole-body glucose metabolism but also requires signals from feeding and fasting cycles to properly maintain glucose levels in the ...

Bias in health care: study highlights discrimination toward children with disabilities

2023-06-27

Children with disabilities, and their families, may face discrimination in in the hospitals and clinics they visit for their health care, according to a new study led by researchers at University of Utah Health. These attitudes may lead to substandard medical treatment, which could contribute to poor health outcomes, say the study’s authors.

“They mistreated her and treated her like a robot. Every single time a nurse walked in the room, they treated her like she was not even there,” said one mother who was interviewed about her child’s health care encounters.

The findings, published in the journal Pediatrics, ...

Molecular imaging identifies brain changes in response to food cues; offers insight into obesity interventions

2023-06-27

Chicago, Illinois (Embargoed until 10:05 a.m. CDT, Tuesday, June 27, 2023)—Molecular imaging with 18F-flubatine PET/MRI has shown that neuroreceptors in the brains of individuals with obesity respond differently to food cues than those in normal-weight individuals, making the neuroreceptors a prime target for obesity treatments and therapy. This research, presented at the Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging 2023 Annual Meeting, contributes to the understanding of the fundamental mechanisms underlying obesity ...

Flexible, supportive company culture makes for better remote work

2023-06-27

The pandemic made remote work the norm for many, but that doesn’t mean it was always a positive experience. Remote work can have many advantages: increased flexibility, inclusivity for parents and people with disabilities, and work-life balance. But it can also cause issues with collaboration, communication, and the overall work environment.

New research from the Georgia Institute of Technology used data from the employee review website Glassdoor to determine what made remote work successful. Companies that catered to employees’ interests, ...

BU study unpacks how medical systems harm the intersex community

2023-06-27

(Boston)— Intersex people’s (people whose sex characteristics do not fit within the strict binary categorizations of male or female) healthcare has received a lot of media attention recently, particularly with the uptick in anti-transgender legislation, which often also targets this community. Discrimination and mistreatment in social and medical settings, largely due to the stigma of not conforming to binary views of sex, results in many intersex individuals experiencing isolation, secrecy and shame, which can have a lasting impact on their mental health.

A new study from researchers at Boston University Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine highlights the need ...

Follow the leader: Researchers identify mechanism of cancer invasion

2023-06-27

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — A cancerous tumor is the accumulation of cells uncontrollably dividing, some of which can invade other parts of the body. The process is difficult to predict in detail, and eradicating the cells poses even greater difficulty. Now, a Penn State-led research team has revealed how the exodus initiates, shedding light on a potential therapeutic target to halt the invasion and providing a prognostic marker to help clinicians select the best treatment option.

They published their findings on June 26 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“Cancer cells don’t randomly detach from the primary tumor and disseminate ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Novel camel antimicrobial peptides show promise against drug-resistant bacteria

Scientists discover why we know when to stop scratching an itch

A hidden reason inner ear cells die – and what it means for preventing hearing loss

Researchers discover how tuberculosis bacteria use a “stealth” mechanism to evade the immune system

New microscopy technique lets scientists see cells in unprecedented detail and color

Sometimes less is more: Scientists rethink how to pack medicine into tiny delivery capsules

Scientists build low-cost microscope to study living cells in zero gravity

The Biophysical Journal names Denis V. Titov the 2025 Paper of the Year-Early Career Investigator awardee

Scientists show how your body senses cold—and why menthol feels cool

Scientists deliver new molecule for getting DNA into cells

Study reveals insights about brain regions linked to OCD, informing potential treatments

Does ocean saltiness influence El Niño?

2026 Young Investigators: ONR celebrates new talent tackling warfighter challenges

Genetics help explain who gets the ‘telltale tingle’ from music, art and literature

Many Americans misunderstand medical aid in dying laws

Researchers publish landmark infectious disease study in ‘Science’

New NSF award supports innovative role-playing game approach to strengthening research security in academia

Kumar named to ACMA Emerging Leaders Program for 2026

AI language models could transform aquatic environmental risk assessment

New isotope tools reveal hidden pathways reshaping the global nitrogen cycle

Study reveals how antibiotic structure controls removal from water using biochar

Why chronic pain lasts longer in women: Immune cells offer clues

Toxic exposure creates epigenetic disease risk over 20 generations

More time spent on social media linked to steroid use intentions among boys and men

New study suggests a “kick it while it’s down” approach to cancer treatment could improve cure rates

Milken Institute, Ann Theodore Foundation launch new grant to support clinical trial for potential sarcoidosis treatment

New strategies boost effectiveness of CAR-NK therapy against cancer

Study: Adolescent cannabis use linked to doubling risk of psychotic and bipolar disorders

Invisible harms: drug-related deaths spike after hurricanes and tropical storms

Adolescent cannabis use and risk of psychotic, bipolar, depressive, and anxiety disorders

[Press-News.org] Deaf mice have nearly normal inner ear function until ear canal opensFindings support placement of cochlear implants early in life