(Press-News.org) PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] — Elephants eat plants. That’s common knowledge to biologists and animal-loving schoolchildren alike. Yet figuring out exactly what kind of plants the iconic herbivores eat is more complicated.

A new study from a global team that included Brown conservation biologists used innovative methods to efficiently and precisely analyze the dietary habits of two groups of elephants in Kenya, down to the specific types of plants eaten by which animals in the group. Their findings on the habits of individual elephants help answer important questions about the foraging behaviors of groups, and aid biologists in understanding the conservation approaches that best keep elephants not only sated but satisfied.

The study was published in the journal Royal Society Open Science.

“It’s really important for conservationists to keep in mind that when animals don’t get enough of the foods that they need, they may survive — but they may not prosper,” said study author Tyler Kartzinel, an assistant professor of environmental studies and of ecology, evolution and organismal biology at Brown. “By better understanding what each individual eats, we can better manage iconic species like elephants, rhinos and bison to ensure their populations can grow in sustainable ways.”

One of the main tools that the scientists used to conduct their study is called DNA metabarcoding, a cutting-edge genetic technique that allows researchers to identify the composition of biological samples by matching the extracted DNA fragments representing an elephant’s food to a library of plant DNA barcodes.

Brown has been developing applications for this technology, said Kartzinel, and bringing together researchers from molecular biology and the computational side to solve problems faced by conservationists in the field.

This is the first use of DNA metabarcoding to answer a long-term question about social foraging ecology, which is how members of a social group — such as a family — decide what foods to eat, Kartzinel said.

“When I talk to non-ecologists, they are stunned to learn that we have never really had a clear picture of what all of these charismatic large mammals actually eat in nature,” Kartzinel said. “The reason is that these animals are difficult and dangerous to observe from up-close, they move long distances, they feed at night and in thick bush and a lot of the plants they feed on are quite small.”

Not only are the elephants hard to monitor, but their food can be nearly impossible to identify by eye, even for an expert botanist, according to Kartzinel, who has conducted field research in Kenya.

Understanding an elephant’s favorite foods

The research group compared the new genetic technique to a method called stable isotope analysis, which involves a chemical analysis of animal hair. Two of the study authors, George Wittemyer at Colorado State University and Thure Cerling at the University of Utah, had previously shown that elephants switch from eating fresh grasses when it rains to eating trees during the long dry season. While this advanced study by allowing researchers to identify broad-scale dietary patterns, they still couldn’t discern the different types of plants in the elephant’s diet.

The scientists had saved fecal samples that had been collected in partnership with the non-profit organization Save the Elephants when Wittemyer and Cerling were conducting the stable isotopes analyses almost 20 years ago. Study author Brian Gill, then a Brown post-doctoral associate, determined that the samples were still usable even after many years in storage.

The team coupled combined analyses of carbon stable isotopes from the feces and hair of elephants with dietary DNA metabarcoding, GPS-tracking and remote-sensing data to evaluate the dietary variation of individual elephants in two groups. They matched each unique DNA sequence in the sample to a collection of reference plants — developed with the botanical expertise of Paul Musili, director of the East Africa Herbarium at the National Museums of Kenya — and compared the diets of individual elephants through time.

In their analysis, they showed that dietary differences among individuals were often far greater than had been previously assumed, even among family members that foraged together on a given day.

This study helps address a classic paradox in wildlife ecology, Kartzinel said: “How do social bonds hold family groups together in a world of limited resources?”In other words, given that elephants all seemingly eat the same plants, it’s not obvious why competition for food doesn’t push them apart and force them to forage independently.

The simple answer is that elephants vary their diets based not only on what’s available but also their preferences and physiological needs, said Kartzinel. A pregnant elephant, for example, may have different cravings and requirements at various times in her pregnancy.

While the study wasn’t designed to explain social behavior, these findings help inform theories of why a group of elephants may forage together: The individual elephants don’t always eat exactly the same plants at the same time, so there will usually be enough plants to go around.

These findings may offer valuable insights for conservation biologists. To protect elephants and other major species and create environments in which they can successfully reproduce and grow their populations, they need a variety of plants to eat. This may also decrease the chances of inter-species competition and prevent the animals from poaching human food sources, such as crops.

“Wildlife populations need access to diverse dietary resources to prosper,” Kartzinel said. “Each elephant needs variety, a little bit of spice — not literally in their food, but in their dietary habits.”

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (DEB-1930820, DEB-2026294, DEB-2046797, and OIA-2033823).

END

Similar to humans, elephants also vary what they eat for dinner every night

2023-07-05

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Endometriosis linked to reduction in live births before diagnosis of the disease

2023-07-05

Endometriosis is linked to a reduction in fertility in the years preceding a definitive surgical diagnosis of the condition, according to new research published today (Wednesday) in Human Reproduction [1], one of the world’s leading reproductive medicine journals.

In the first study to look at birth rates in a large group of women who eventually received a surgical verification of endometriosis, researchers in Finland found that the number of first live births in the period before diagnosis was half that of women without the painful condition. ...

Apex predator of the Cambrian likely sought soft over crunchy prey

2023-07-05

Biomechanical studies on the arachnid-like front “legs” of an extinct apex predator show that the 2-foot (60-centimeter) marine animal Anomalocaris canadensis was likely much weaker than once assumed. One of the largest animals to live during the Cambrian, it was probably agile and fast, darting after soft prey in the open water rather than pursuing hard-shelled creatures on the ocean floor. The study is published today in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

First discovered in the late 1800s, Anomalocaris canadensis—which means “weird shrimp from Canada” in Latin—has long been thought to be responsible ...

Warmer and murkier waters favour predators of guppies, study finds

2023-07-05

Changes in water conditions interact to affect how Trinidadian guppies protect themselves from predators, scientists at the University of Bristol have discovered.

Known stressors, such as increased temperature and reduced visibility, when combined, cause this fish to avoid a predator less, and importantly, form looser protective shoals.

The findings, published today in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B, show guppies’ responses are more affected by the interaction of these stressors than if they acted independently.

Natural ...

Vineyard fungicides pose a threat to survival of wild birds

2023-07-04

New research reveals that wild birds living in vineyards can be highly susceptible to contamination by triazole fungicides, more so than in other agricultural landscapes. Exposure to these fungicides at a field-realistic level were found to disrupt hormones and metabolism, which can impact bird reproduction and survival.

“We found that birds can be highly contaminated by triazoles in vineyards,” says Dr Frédéric Angelier, Senior Researcher at the French National Center for Scientific Research, France. “This contamination was much higher in vineyards relative to other crops, emphasizing that contaminants may especially put birds at risk in these ...

World’s most threatened seabirds visit remote plastic pollution hotspots, study finds

2023-07-04

UNDER STRICT EMBARGO UNTIL 16:00 LONDON TIME (BST) / 11:00 (US ET) ON TUESDAY 4TH JULY 2023

Analysis of global tracking data for 77 species of petrel has revealed that a quarter of all plastics potentially encountered in their search for food are in remote international waters – requiring international collaboration to address.

The extensive study assessed the movements of 7,137 individual birds from 77 species of petrel, a group of wide-ranging migratory seabirds including the Northern Fulmar and European Storm-petrel, and the Critically Endangered Newell’s Shearwater.

This is ...

Sea of plastic: Mediterranean is the area of the world most at risk for endangered seabirds

2023-07-04

New study reveals the areas most at risk of plastic exposure by the already endangered seabirds.

The study, now published in Nature Communications, brings together more than 200 researchers worldwide around a pressing challenge, widely recognized as a growing threat to marine life: the pollution of oceans by plastic. Coordinated by Dr. Maria Dias, researcher at the Centre for Ecology, Evolution and Environmental Changes (cE3c) at the Faculty of Sciences of the University of Lisbon (Ciências ULisboa), ...

Omega-3 oil counteracts toxic effects of pesticides in pollinators

2023-07-04

New research suggests that the use of an omega-3 rich oil called “ahiflower oil” can prevent damage to honey bee mitochondria caused by neonicotinoid pesticides. This research is part of an ongoing project by PhD student Hichem Menail of the Université de Moncton in New Brunswick, Canada.

“Pesticides are a major threat to insect populations and as insects are at the core of ecosystem richness and balance, any loss in insect biodiversity can lead to catastrophic outcome,” says Mr Menail, adding that pesticide-related pollinator declines are also a huge concern for food crops globally.

Imidacloprid, ...

Global efforts to reduce infectious diseases must extend beyond early childhood

2023-07-04

Global efforts to reduce infectious disease rates must have a greater focus on older children and adolescents after a shift in disease burden onto this demographic, according to a new study.

The research, led by Murdoch Children’s Research Institute and the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, has found that infectious disease control has largely focused on children aged under five, with scarce attention on young people between five and 24 years old.

Published in The Lancet, the study found three million children and adolescents die from infectious diseases every year, equivalent to one death every 10 seconds. It looked at data across 204 countries ...

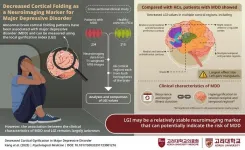

Korea University Medicine study highlights a new biomarker for major depressive disorder

2023-07-04

In appearance, the human brain’s outermost layer, called the cortex, is a maze of tissue folds. The peaks or raised surfaces of these folds, called gyri, play an important role in the proper functioning of the brain. Improper gyrification—or the development of gyri—has been implicated in various neurological disorders, one of them being the debilitating and widespread mental illness, major depressive disorder (MDD). Although prior studies have shown that abnormal cortical folding patterns are associated with MDD, ...

Luísa Figueiredo was elected as an EMBO member

2023-07-04

The European Molecular Biology Organization (EMBO) has announced today that it will award the lifetime honor of EMBO Membership to Luísa Figueiredo, group leader at the Instituto de Medicina Molecular João Lobo Antunes (iMM, Lisbon, Portugal), in recognition of the excellence of her research and outstanding achievements in the life sciences. EMBO is an international organization of more than 2000 life scientists in Europe and around the world, committed to build a European research environment where scientists can achieve their best work. Aside from Luísa Figueiredo, 68 other EMBO Members have been elected this year.

Luísa ...