(Press-News.org) New device shows promise in small animal studies

Not only can it restore normal heart rhythms, it also can show which areas of the heart are functioning well and which areas are not

After the device is no longer needed, it harmlessly dissolves inside the body, bypassing the need for extraction

EVANSTON, Ill. — Nearly 700,000 people in the United States die from heart disease every year, and one-third of those deaths result from complications in the first weeks or months following a traumatic heart-related event.

To help prevent those deaths, researchers at Northwestern and George Washington (GW) universities have developed a new device to monitor and treat heart disease and dysfunction in the days, weeks or months following such events. And, after the device is no longer needed, it harmlessly dissolves inside the body, bypassing the need for extraction.

About the size of a postage stamp, the soft, flexible device uses an array of sensors and actuators to perform more complicated investigations than traditional devices, such as pacemakers, can accomplish. Not only can it be placed on various sections of the heart, the device also continuously streams information to physicians, so they can remotely monitor a patient’s heart in real time. The device also is highly transparent, allowing physicians to observe specific heart regions to make a diagnosis or provide a treatment.

The research will be published on Wednesday (July 5) in the journal Science Advances.

“Several serious complications, including atrial fibrillation and heart block, can follow cardiac surgeries or catheter-based therapies,” said Northwestern’s Igor Efimov, an experimental cardiologist who co-led the study. “Current post-surgical monitoring and treatment of these complications require more sophisticated technology than currently available. We hope our new device can close this gap in technology. Our transient electronic device can map electrical activity from numerous locations on the atria and then deliver electrical stimuli from many locations to stop atrial fibrillation as soon as it starts.”

“Many deaths that occur following heart surgery or a heart attack could be prevented if doctors had better tools to monitor and treat patients in the delicate weeks and months after these events take place,” added GW’s Luyao Lu, who co-led the work with Efimov. “The tool developed in our work has great potential to address unmet needs in many programs of fundamental and translational cardiac research.”

Efimov is a professor of biomedical engineering at Northwestern’s McCormick School of Engineering and professor of medicine at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. Lu is an assistant professor of biomedical engineering at GW.

This work builds on Efimov’s previous work to develop cardiac implants to monitor and temporarily pace the heart. In 2021, Efimov and Northwestern professor John A. Rogers introduced the first-ever transient pacemaker, published in Nature Biomedical Engineering. Then, earlier this year, Efimov’s team unveiled a graphene “tattoo” for treating cardiac arrhythmia, published in Advanced Materials.

“After heart surgeries, surgeons sometimes insert temporary wires, which are connected to external current generators, to provide electrical stimulation during temporary heart block caused by the surgery,” Efimov said. “Recently, we developed a bioresorbable pacemaker to replace such a wire. Post-operative atrial fibrillation requires a more complicated approach based on a multi-electrode array for sensing and stopping atrial fibrillation. Now, we present a novel technology to achieve this goal.”

Tested in small animal models, the new device provides functions beyond those of a traditional pacemaker. While a pacemaker only can provide one overall picture of the heart (whether or not the heart is beating), the transient device provides a more nuanced picture. Not only can it restore normal heart rhythms, it also can show which areas of the heart are functioning well and which areas are not. The device’s transparent nature also allows researchers to optically map many important cardiac physical parameters through the device to better study heart function and heart disease mechanisms.

After a clinically relevant period, the device — which is made of biocompatible materials approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration — simply dissolves into benign products. Similar to absorbable stitches, the device degrades and then completely disappears through the body’s natural biological processes. The device’s bioresorbable nature could reduce healthcare costs and improve patient outcomes by avoiding complications from surgical extraction and lowering infection risks.

The study, “Soft, bioresorbable, transparent microelectrode arrays for multimodal spatiotemporal mapping and modulation of cardiac physiology,” was supported by the National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health.

END

A team of astrophysicists at the University of Toronto (U of T) has revealed how the slow and steady lengthening of Earth’s day caused by the tidal pull of the moon was halted for over a billion years.

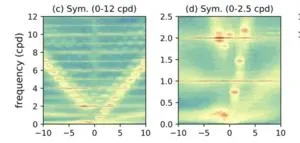

They show that from approximately two billion years ago until 600 million years ago, an atmospheric tide driven by the sun countered the effect of the moon, keeping Earth’s rotational rate steady and the length of day at a constant 19.5 hours.

Without this billion-year pause in the slowing of our planet’s rotation, our current 24-hour day would stretch to over 60 hours.

The ...

Article URL: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0287112

Article Title: Contributions of neighborhood social environment and air pollution exposure to Black-White disparities in epigenetic aging

Author Countries: USA

Funding: This work was supported by National Institute on Aging: R01-AG066152 (CM), R01- AG070885 (RB), P30-AG072979 (CM). Additional support includes Pennsylvania Department of Health (2019NF4100087335; CM), and Penn Institute on Aging (CM). National Institute on Aging: https://www.nia.nih.gov Pennsylvania Department of Health: https://www.health.pa.gov/Pages/default.aspx Penn Institute on Aging: https://www.med.upenn.edu/aging/. ...

New research from the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology & Neuroscience (IoPPN) at King’s College London and City University New York, published today (Wednesday 5 July) in JAMA Psychiatry, has found that the way childhood abuse and/or neglect is remembered and processed has a greater impact on later mental health than the experience itself. The authors suggest that, even in the absence of documented evidence, clinicians can use patients’ self-reported experiences of abuse and neglect to identify those at risk of developing mental health difficulties ...

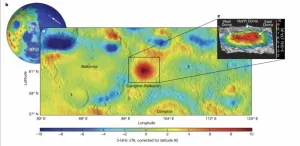

DALLAS (SMU) – A large formation of granite discovered below the lunar surface likely was formed from the cooling of molten lava that fed a volcano or volcanoes that erupted early in the Moon’s history – as long as 3.5 billion years ago.

A team of scientists led by Matthew Siegler, an SMU research professor and research scientist with the Planetary Science Institute, has published a study in Nature that used microwave frequency data to measure heat below the surface of a suspected volcanic ...

We interact with bits and bytes everyday – whether that’s through sending a text message or receiving an email.

There’s also quantum bits, or qubits, that have critical differences from common bits and bytes. These photons – particles of light – can carry quantum information and offer exceptional capabilities that can’t be achieved any other way. Unlike binary computing, where bits can only represent a 0 or 1, qubit behavior exists in the realm of quantum mechanics. Through “superpositioning,” a qubit can represent a 0, ...

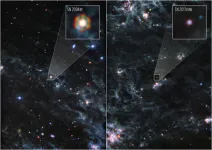

Researchers using NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope have made major strides in confirming the source of dust in early galaxies. Observations of two Type II supernovae, Supernova 2004et (SN 2004et) and Supernova 2017eaw (SN 2017eaw), have revealed large amounts of dust within the ejecta of each of these objects. The mass found by researchers supports the theory that supernovae played a key role in supplying dust to the early universe.

Dust is a building block for many things in our universe – planets in particular. As dust from dying stars spreads through space, it carries essential elements to help give birth to the next generation of stars ...

Danish researchers solve the mystery of how deadly virus hide in humans

With a new method for examining virus samples researchers from the University of Copenhagen have solved an old riddle about how Hepatitis C virus avoids the human body's immune defenses. The result may have an impact on how we track and treat viral diseases in general.

An estimated 50 million people worldwide are infected with with chronic hepatitis C. The hepatitis C virus can cause inflammation and scarring of the liver, and in the worst case, liver cancer. Hepatitis C was discovered in 1989 and is one of the most studied viruses on the planet. Yet for decades, how it manages to evade the human immune ...

A study of the genetic variation that makes mice more susceptible to bowel inflammation after a high-fat diet has identified candidate genes which may drive inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in humans. The findings are published as a Reviewed Preprint in eLife.

Described by the editors as a fundamental study, the work provides a framework for using systems genetics approaches to dissect the complex mechanisms of gut physiology. The authors show how it is possible to use genetically diverse but well-characterised mice to interrogate intestinal inflammation and pinpoint genes influenced by the environment ...

Most people have at some point in their life suffered an intestinal infection or food poisoning forcing them to stay close to the bathroom. It is very uncomfortable. Most of the time, though, it passes quickly.

But around 60,000-100,000 Danes suffer from a form of chronic diarrhoea called bile acid malabsorption or bile acid diarrhoea.

It is a chronic condition characterised by frequent and sudden diarrhoea more than 10 times a day. Even though the disease is not life-threatening, it can seriously ...

PULLMAN, Wash. -- Kenyan patients who spend more than three days in the nation’s hospitals are more likely to harbor a form of bacteria resistant to one of the most widely used antibiotic classes, according to a recent study led by Washington State University.

The research team found that 66% of hospitalized patients were colonized with bacteria resistant to third-generation cephalosporins, compared to 49% among community residents. Third-generation cephalosporins are typically used for serious infections, and resistance to these antibiotics ...