(Press-News.org) A study of 273 people found that brain circuits associated with depression were different between people with traumatic brain injury and those without TBI.

The study suggests depression after TBI may not be the same as depression related to other causes.

A new study led by Shan Siddiqi, MD, from Brigham and Women’s Hospital, a founding member of the Mass General Brigham healthcare system, suggests that depression after traumatic brain injury (TBI) could be a clinically distinct disorder rather than traditional major depressive disorder, with implications for patient treatment. The findings are published in Science Translational Medicine.

“Our findings help explain how the physical trauma to specific brain circuits can lead to development of depression. If we’re right, it means that we should be treating depression after TBI like a distinct disease,” said corresponding author Shan Siddiqi, MD, of the Brigham’s Department of Psychiatry and Center for Brain Circuit Therapeutics. “Many clinicians have suspected that this is a clinically distinct disorder with a unique pattern of symptoms and unique treatment response, including poor response to conventional antidepressants – but until now, we didn’t have clear physiological evidence to prove this.”

Siddiqi collaborated with researchers from Washington University in St. Louis, Duke University School of Medicine, the University of Padua, and the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences on the study. The work started as a side project seven years ago when Siddiqi was motivated by a patient he shared with David Brody, MD, PhD, a co-author on the study and a neurologist at Uniformed Services University. The two started a small clinical trial that used personalized brain mapping to target brain stimulation as a treatment for TBI patients with depression. In the process, they noticed a specific pattern of abnormalities in these patients’ brain maps.

The current study included 273 adults with TBI, usually from sports injuries, military injuries, or car accidents. People in this group were compared to other groups who did not have a TBI or depression, people with depression without TBI, and people with posttraumatic stress disorder. Study participants went through a resting-state functional connectivity MRI, a brain scan that looks at how oxygen is moving in the brain. These scans gave information about oxygenation in up to 200,000 points in the brain at about 1,000 different points in time, leading to about 200 million data points in each person. Based on this information, a machine learning algorithm was used to generate an individualized map of each person’s brain.

The location of the brain circuit involved in depression was the same among people with TBI as people without TBI, but the nature of the abnormalities was different. Connectivity in this circuit was decreased in depression without TBI and was increased in TBI-associated depression. This implies that TBI-associated depression may be a different disease process, leading the study authors to propose a new name: “TBI affective syndrome.”

“I've always suspected it isn't the same as regular major depressive disorder or other mental health conditions that are not related to traumatic brain injury,” said Brody. “There's still a lot we don't understand, but we're starting to make progress.”

One limitation of the trial is that with so much data, the researchers were not able to do detailed assessments of each patient beyond brain mapping. As a future step, investigators would like to assess participants’ behavior in a more sophisticated way and potentially define different kinds of TBI-associated neuropsychiatric syndromes.

Siddiqi and Brody are also using this approach to develop personalized treatments. Originally, they set out to design a new treatment in which they used this brain mapping technology to target a specific brain region for people with TBI and depression, using transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS). They enrolled 15 people in the pilot and saw success with the treatment. Since then, they have received funding to replicate the study in a multicenter military trial.

“We hope our discovery guides a precision medicine approach to managing depression and mild TBI, and perhaps even intervene in neuro-vulnerable trauma survivors before the onset of chronic symptoms,” said Rajendra Morey, MD, a professor of psychiatry at Duke University School of Medicine, and co-author on the study.

Disclosures: Dr. Siddiqi is a scientific consultant for Magnus Medical and a clinical consultant for

Acacia Mental Health, Kaizen Brain Center, and Boston Precision Neurotherapeutics. He has received

investigator-initiated research funding independently from Neuronetics and BrainsWay. He has served

as a speaker for BrainsWay (branded) and PsychU.org (unbranded, sponsored by Otsuka). He owns stock

in BrainsWay (publicly traded) and Magnus Medical (not publicly traded). DLB has served as a consultant for Pfizer Inc, Intellectual Ventures, Signum Nutralogix, Kypha Inc, Sage Therapeutics, iPerian Inc, Navigant, Avid Radiopharmaceuticals (Eli Lilly & Co), the St Louis County Public Defender, the United States Attorney’s Office, the St Louis County Medical Examiner, GLG, Stemedica, Luna Innovations, and QualWorld. DLB holds equity in the company Inner Cosmos. DLB receives royalties from sales of Concussion Care Manual (Oxford University Press) and an honorarium from Mary Ann Liebert Inc for services as Editor-in-Chief of Journal of Neurotrauma. No conflicts of interest with the presented work. DLB is an employee of the Department of Defense; the views expressed here do not reflect those of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, the US Department of Defense, or the US Government.

Funding: The study protocol was funded by the McDonnell Center for Systems Neuroscience (New Resource Proposal) and the Mallinckrodt Institute of Radiology (funding for scans). SHS received fellowship support from the Sidney R. Baer Foundation. SHS received salary support from the Center for

Neuroscience and Regenerative Medicine at the Uniformed Services University for Health Sciences. SHS

is currently funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (K23MH121657 and R01MH113929), the

Brain & Behavior Research Foundation, and the Baszucki Family Foundation. DLB was an employee of

Washington University at the time the study was conducted and is now an employee of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Science, Department of Defense.

Paper cited: Siddiqi, S.H. et al. “Precision functional MRI mapping reveals distinct connectivity patterns for depression associated with traumatic brain injury” Science Translational Medicine DOI: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abn0441

###

About Mass General Brigham

Mass General Brigham is an integrated academic health care system, uniting great minds to solve the hardest problems in medicine for our communities and the world. Mass General Brigham connects a full continuum of care across a system of academic medical centers, community and specialty hospitals, a health insurance plan, physician networks, community health centers, home care, and long-term care services. Mass General Brigham is a nonprofit organization committed to patient care, research, teaching, and service to the community. In addition, Mass General Brigham is one of the nation’s leading biomedical research organizations with several Harvard Medical School teaching hospitals. For more information, please visit massgeneralbrigham.org.

END

Depression after traumatic brain injury could represent a new, distinct disease

2023-07-05

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Earth formed from dry, rocky building blocks

2023-07-05

Billions of years ago, in the giant disk of dust, gas, and rocky material that orbited our young sun, larger and larger bodies coalesced to eventually give rise to the planets, moons, and asteroids we see today. Scientists are still trying to understand the processes by which planets, including our home planet, were formed. One way researchers can study how Earth formed is to examine the magmas that flow up from deep within the planet’s interior. The chemical signatures from these samples contain a record of the timing and the nature of the materials that came together to form ...

Lasering lava to forecast volcanic eruptions

2023-07-05

University of Queensland researchers have optimised a new technique to help forecast how volcanoes will behave, which could save lives and property around the world.

Dr Teresa Ubide from UQ’s School of the Environment and a team of international collaborators have trialled a new application of the tongue-twisting approach: laser ablation inductively coupled plasma quadruple mass spectrometry.

“It’s a mouthful, but this high-resolution technique offers clearer data on what’s chemically occurring within a volcano’s magma, which is fundamental to forecasting eruption patterns and changes,” Dr Ubide said.

She described magma ...

Dissolving cardiac device monitors, treats heart disease

2023-07-05

New device shows promise in small animal studies

Not only can it restore normal heart rhythms, it also can show which areas of the heart are functioning well and which areas are not

After the device is no longer needed, it harmlessly dissolves inside the body, bypassing the need for extraction

EVANSTON, Ill. — Nearly 700,000 people in the United States die from heart disease every year, and one-third of those deaths result from complications in the first weeks or months following a traumatic heart-related event.

To help prevent those deaths, researchers at Northwestern ...

Why the day is 24 hours long: Astrophysicists reveal why Earth’s day was a constant 19.5 hours for over a billion years

2023-07-05

A team of astrophysicists at the University of Toronto (U of T) has revealed how the slow and steady lengthening of Earth’s day caused by the tidal pull of the moon was halted for over a billion years.

They show that from approximately two billion years ago until 600 million years ago, an atmospheric tide driven by the sun countered the effect of the moon, keeping Earth’s rotational rate steady and the length of day at a constant 19.5 hours.

Without this billion-year pause in the slowing of our planet’s rotation, our current 24-hour day would stretch to over 60 hours.

The ...

Black Americans may face relatively accelerated biological aging because they tend to experience lower socioeconomic status, more neighborhood deprivation and higher air pollution than White Americans

2023-07-05

Article URL: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0287112

Article Title: Contributions of neighborhood social environment and air pollution exposure to Black-White disparities in epigenetic aging

Author Countries: USA

Funding: This work was supported by National Institute on Aging: R01-AG066152 (CM), R01- AG070885 (RB), P30-AG072979 (CM). Additional support includes Pennsylvania Department of Health (2019NF4100087335; CM), and Penn Institute on Aging (CM). National Institute on Aging: https://www.nia.nih.gov Pennsylvania Department of Health: https://www.health.pa.gov/Pages/default.aspx Penn Institute on Aging: https://www.med.upenn.edu/aging/. ...

Memories of childhood abuse and neglect has greater impact on mental health than the experience itself

2023-07-05

New research from the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology & Neuroscience (IoPPN) at King’s College London and City University New York, published today (Wednesday 5 July) in JAMA Psychiatry, has found that the way childhood abuse and/or neglect is remembered and processed has a greater impact on later mental health than the experience itself. The authors suggest that, even in the absence of documented evidence, clinicians can use patients’ self-reported experiences of abuse and neglect to identify those at risk of developing mental health difficulties ...

Large sub-surface granite formation signals ancient volcanic activity on Moon's dark side

2023-07-05

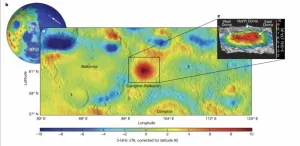

DALLAS (SMU) – A large formation of granite discovered below the lunar surface likely was formed from the cooling of molten lava that fed a volcano or volcanoes that erupted early in the Moon’s history – as long as 3.5 billion years ago.

A team of scientists led by Matthew Siegler, an SMU research professor and research scientist with the Planetary Science Institute, has published a study in Nature that used microwave frequency data to measure heat below the surface of a suspected volcanic ...

Finding the flux of quantum technology

2023-07-05

We interact with bits and bytes everyday – whether that’s through sending a text message or receiving an email.

There’s also quantum bits, or qubits, that have critical differences from common bits and bytes. These photons – particles of light – can carry quantum information and offer exceptional capabilities that can’t be achieved any other way. Unlike binary computing, where bits can only represent a 0 or 1, qubit behavior exists in the realm of quantum mechanics. Through “superpositioning,” a qubit can represent a 0, ...

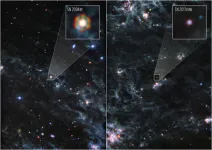

Webb locates dust reservoirs in two supernovae

2023-07-05

Researchers using NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope have made major strides in confirming the source of dust in early galaxies. Observations of two Type II supernovae, Supernova 2004et (SN 2004et) and Supernova 2017eaw (SN 2017eaw), have revealed large amounts of dust within the ejecta of each of these objects. The mass found by researchers supports the theory that supernovae played a key role in supplying dust to the early universe.

Dust is a building block for many things in our universe – planets in particular. As dust from dying stars spreads through space, it carries essential elements to help give birth to the next generation of stars ...

Danish researchers solve the mystery of how deadly virus hide in humans

2023-07-05

Danish researchers solve the mystery of how deadly virus hide in humans

With a new method for examining virus samples researchers from the University of Copenhagen have solved an old riddle about how Hepatitis C virus avoids the human body's immune defenses. The result may have an impact on how we track and treat viral diseases in general.

An estimated 50 million people worldwide are infected with with chronic hepatitis C. The hepatitis C virus can cause inflammation and scarring of the liver, and in the worst case, liver cancer. Hepatitis C was discovered in 1989 and is one of the most studied viruses on the planet. Yet for decades, how it manages to evade the human immune ...