(Press-News.org) RICHMOND, Va. (July 13, 2023) — A new study by a Virginia Commonwealth University researcher has found that aggression is not always the product of poor self-control but, instead, often can be the product of successful self-control in order to inflict greater retribution.

The new paper, “Aggression As Successful Self-Control,” by corresponding author David Chester, Ph.D., an associate professor of social psychology in the Department of Psychology at VCU’s College of Humanities and Sciences, was published by the journal Social and Personality Psychology Compass and uses meta-analysis to summarize evidence from dozens of existing studies in psychology and neurology.

“Typically, people explain violence as the product of poor self-control,” Chester said. “In the heat of the moment, we often fail to inhibit our worst, most aggressive impulses. But that is only one side of the story.”

Indeed, Chester’s study found that the most aggressive people do not have personalities characterized by poor self-discipline and that training programs that boost self-control have not proved effective in reducing violent tendencies. Instead, the study found ample evidence that aggression can arise from successful self-control.

“Vengeful people tend to exhibit greater premeditation of their behavior and self-control, enabling them to delay the gratification of sweet revenge and bide their time to inflict maximum retribution upon those who they believe have wronged them,” Chester said. “Even psychopathic people, who comprise the majority of people who commit violent offenses, often exhibit robust development of inhibitory self-control over their teenage years.”

Aggressive behavior is reliably linked to increased – not just decreased – activity in the brain’s prefrontal cortex, a biological substrate of self-control, Chester found. The findings make it clear that the argument that aggression is primarily the product of poor self-control is weaker than previously thought.

“This paper pushes back against a decades-long dominant narrative in aggression research, which is that violence starts when self-control stops,” Chester said. “Instead, it argues for a more balanced, nuanced view in which self-control can both constrain and facilitate aggression, depending on the person and the situation.”

The findings also argue for more caution in the implementation of treatments, therapies and interventions that seek to reduce violence by improving self-control, Chester said.

“Many interventions seek to teach people to inhibit their impulses, but this new approach to aggression suggests that although this may reduce aggression for some people, it is also likely to increase aggression for others,” he said. “Indeed, we may be teaching some people how best to implement their aggressive tendencies.”

The findings surprised Chester, a psychologist whose team frequently studies the causes of human aggression.

“Over the years, much of our research was guided by the field’s assumption that aggression is an impulsive behavior characterized by poor self-control,” he said. “But as we started to investigate the psychological characteristics of vengeful and psychopathic people, we quickly realized that such aggressive individuals do not just have self-regulatory deficits; they have many psychological adaptations and skills that enable them to hurt others by using self-control.”

Chester and his team plan to continue exploring questions around aggression and self-control based on the study’s findings.

“Our research going forward is now guided by this new paradigm shift in thinking: that aggression is often the product of sophisticated and complex mental processes and not just uninhibited impulses,” Chester said.

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, part of the National Institutes of Health.

###

About VCU and VCU Health

Virginia Commonwealth University is a major, urban public research university with national and international rankings in sponsored research. Located in downtown Richmond, VCU enrolls more than 28,000 students in 244 degree and certificate programs in the arts, sciences and humanities. Forty-one of the programs are unique in Virginia, many of them crossing the disciplines of VCU’s 12 schools and three colleges. The VCU Health brand represents the VCU health sciences academic programs, the VCU Massey Cancer Center and the VCU Health System, which comprises VCU Medical Center (the only academic medical center in the region), Community Memorial Hospital, Tappahannock Hospital, Children’s Hospital of Richmond at VCU, and MCV Physicians. The clinical enterprise includes a collaboration with Sheltering Arms Institute for physical rehabilitation services. For more, please visit vcu.edu and vcuhealth.org.

END

A person’s ‘mindreading ability’ can predict how well they are able to cooperate, even with people they have never met before.

Researchers at the University of Birmingham found that people with strong mind reading abilities – the ability to understand and take the perspective of another person’s feelings and intentions– are more successful in cooperating to complete tasks than people with weaker mind reading abilities.

These qualities, also called ‘theory of mind’, are not necessarily related to intelligence and could be improved through training programmes to foster improved cooperation, for example in ...

Use of low-dose atropine eyedrops (concentration 0.01%) was no better than placebo at slowing myopia (nearsightedness) progression and elongation of the eye among children treated for two years, according to a randomized controlled trial conducted by the Pediatric Eye Disease Investigator Group (PEDIG) and funded by the National Eye Institute (NEI). The trial aimed to identify an effective way to manage this leading and increasingly common cause of refractive error, which can cause serious uncorrectable vision loss later in life. Results from the trial were published in JAMA Ophthalmology.

Importantly, the findings contradict results from recent trials, primarily in East Asia, which ...

About The Study: In this randomized clinical trial of school-age children in the U.S. with low to moderate myopia (nearsightedness), atropine, 0.01%, eye drops administered nightly when compared with placebo did not slow myopia progression or axial elongation. These results do not support use of atropine, 0.01%, eye drops to slow myopia progression or axial elongation in U.S. children.

Authors: Michael X. Repka, M.D., M.B.A., of the Wilmer Eye Institute in Baltimore, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this ...

About The Study: This study provides evidence of the clinical effectiveness of mRNA-based vaccines against COVID-19 in patients with cancer. Longevity of immunity in preventing severe COVID-19 outcomes in actively treated patients with cancer, cancer survivors, and matched controls was observed at least five months after the third or fourth dose.

Authors: Raghav Sundar, M.B.B.S., Ph.D., of the National University Health System in Singapore, and Kelvin Bryan Tan, Ph.D., of the Ministry of Health in Singapore, are the corresponding authors.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our ...

About The Study: In this survey study, all types of objectively measured visual impairment were associated with a higher dementia prevalence. As most visual impairment is preventable, prioritizing vision health may be important for optimizing cognitive function.

Authors: Joshua R. Ehrlich, M.D., M.P.H., of the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2023.2854)

Editor’s Note: Please see the article for ...

RESEARCH REVEALS HOW COVID-19 VIRUS INFECTS THE PLACENTA, AND HOW THIS CAN BE PREVENTED

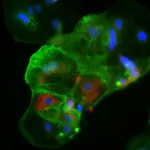

In a landmark study published in Nature Cell Biology, Australian researchers, led by Professor Jose Polo from Monash University and the University of Adelaide and University of Melbourne’s Professor Kanta Subbarao from the Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity (Doherty Institute), have revealed how COVID-19 can infect the human placenta.

Research has shown that COVID-19 infections during pregnancy ...

From Aristotle’s musings on the nature of time to Einstein’s theory of relativity, humanity has long pondered: how do we perceive and understand time? The theory of relativity posits that time can stretch and contract, a phenomenon known as time dilation. Just as the cosmos warps time, our neural circuits can stretch and compress our subjective experience of time. As Einstein famously quipped, “Put your hand on a hot stove for a minute, and it seems like an hour. Sit with a pretty girl for an hour, and it seems like a minute”.

In new work ...

Two pathologies drive the progression of Alzheimer’s disease. Early on, amyloid beta plaques lead the way, but around the time cognitive symptoms arise, tau tangles take over as the driving force and cognition steadily declines. Tracking the course of the disease in individual patients has been challenging because there’s been no easy way to measure tau tangles in the brain.

But now, researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and Lund University in Lund, Sweden, have identified a form of tau that could serve as a marker to track Alzheimer’s progression. The marker also could be used by Alzheimer’s drug developers to assess ...

Routing signals and isolating them against noise and back-reflections are essential in many practical situations in classical communication as well as in quantum processing. In a theory-experimental collaboration, a team led by Andreas Nunnenkamp from the University of Vienna and Ewold Verhagen based at the research institute AMOLF in Amsterdam has achieved unidirectional transport of signals in pairs of "one-way streets". This research published in Nature Physics opens up new possibilities for more flexible signaling devices.

Devices that allow ...

Doctors in Seattle are reporting a history-making case in which a patient received two donor organs, a liver and a heart, to prevent the extreme likelihood that her body would reject a donor heart transplanted alone. In this innovative case, the organ recipient’s own healthy liver was transplanted, domino-like, into a second patient who had advanced liver disease.

The dual-organ recipient, Adriana Rodriguez, 31, of Bellingham, Washington, has recovered well since the Jan. 14, 2023, procedures, said Dr. Shin Lin, a cardiologist ...