(Press-News.org) Mountain ranges play a key role in global climate, altering weather and shaping the flora and fauna that inhabit their slopes and the valleys below. As warm air rises windward grades and cools, moisture condenses into rain and snow. On the leeward side, it’s quite the opposite. Deserts prevail, a phenomenon known as rain shadow. Thus, the way mountain ranges form is a matter of intense interest among those who study and model climates of the past.

That debate will soon grow more heated with a new paper in the journal Nature Geoscience. A team of researchers at the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability has adapted a technique used to study meteorites to measure historic altitudes in sedimentary rocks to show that one of the world’s most familiar mountain ranges, the Himalayas, did not form as experts have long assumed.

“The controversy rests mainly in what existed before the Himalayas were there,” explains Page Chamberlain, professor of Earth and planetary sciences and of Earth system science at the Doerr School of Sustainability, and senior author of the study. “Our study shows for the first time that the edges of the two tectonic plates were already quite high prior to the collision that created the Himalayas – about 3.5 kilometers on average.”

“That’s more than 60 percent of their present height,” added Daniel Ibarra, BS ’12, MS ’14, PhD ’18, a recent postdoctoral researcher from Chamberlain’s lab, first author of the paper, and now an assistant professor at Brown University. “That’s a lot higher than many thought and this new understanding could reshape theories about past climate and biodiversity.”

At the very least, the findings mean that ancient climate models will have to be recalibrated, and it will likely lead to new paleoclimatic assumptions about the Himalayan region of Southern Tibet, an area known as the Gangdese Arc. It could also beget closer scrutiny of other key mountain ranges, such as the Andes and the Sierra Nevada.

Old technique, new insight

Why this longstanding debate is suddenly roiling has much to do with the challenges of measuring topographic altitudes of the past – a field known as paleoaltimetry. It is extremely challenging work, the researchers say. There are not many proxies for altitude in the geologic record, but the Stanford team found one in collaboration with study authors from China University of Geosciences (Beijing).

Not only do rains fall more heavily on windward slopes, but the chemical composition of the precipitation changes as the air rises toward the peaks. Heavier isotopes tend to drop out first; lighter ones nearer the peaks. Thus, by analyzing the isotopic makeup of the rocks, experts can find the telltale signs of the altitude at which they were laid down.

In the sedimentary record, oxygen exists in three stable isotopes: oxygen 16, 17, 18. Dauntingly, the key isotope, oxygen 17, is extremely rare. It comprises just 0.04% of the oxygen on Earth. That means, in a sample containing a million atoms of oxygen, just four atoms are oxygen 17.

“There are maybe eight labs in the world that can do this analysis,” said Chamberlain, who helped process samples at the Terrestrial Paleoclimate lab at Stanford. “Still, it took us three years to get numbers that made some sense and that were working every day.”

Tectonic shifts

That explains why triple oxygen analysis had been overlooked – or perhaps too easily dismissed – as a proxy for ancient altitude. But Chamberlain and his colleagues saw an opportunity. Using a grant from the Heising-Simons Foundation, the team adapted the technique to paleoaltimetry and used the mountains of Sun Valley, Idaho, for a proof-of-concept paper in 2020. With the science established, they then turned their sights higher – to the Himalayas.

Sampling quartz veins from lower altitudes in southern Tibet and using triple oxygen analysis, the team showed that the foundations of the Gangdese Arc were already much higher than anticipated, long before any tectonic collision occurred.

“Experts have long thought that it takes a massive tectonic collision, on the order of continent-to-continent scale, to produce the sort of uplift required to produce Himalaya-scale elevations,” Ibarra said. “This study disproves that and sends the field in some interesting new directions.”

Contributing authors include Yuan Gao, Jingen Dai, and Chengshan Wang at China University of Geosciences (Beijing). Chamberlain is also a member of Bio-X and an affiliate with the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment.

END

Before reaching the skies, the Himalayas had a leg up, new study shows

2023-08-10

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Scientists harness the power of AI to shed light on different types of Parkinson’s disease

2023-08-10

Francis Crick Institute press release

Under strict embargo: 16:00hrs BST 10 August 2023

Peer reviewed

Observational study

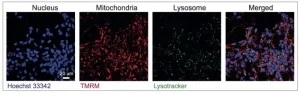

Cells

Researchers at the Francis Crick Institute and UCL Queen Square Institute of Neurology, working with technology company Faculty AI, have shown that machine learning can accurately predict subtypes of Parkinson’s disease using images of patient-derived stem cells.

Their work, published today in Nature Machine Intelligence, has shown that computer models can accurately classify four subtypes of Parkinson’s disease, with one reaching an accuracy of 95%. This could pave the way for personalised medicine and targeted drug discovery.

Parkinson’s ...

Researchers discover a potential application of unwanted electronic noise in semiconductors

2023-08-10

Random Telegraph Noise (RTN), a type of unwanted electronic noise, has long been a nuisance in electronic systems, causing fluctuations and errors in signal processing. However, a team of researchers from the Center for Integrated Nanostructure Physics within the Institute for Basic Science (IBS), South Korea has made an intriguing breakthrough that can potentially harness these fluctuations in semiconductors. Led by Professor LEE Young Hee, the team reported that magnetic fluctuations and their gigantic RTN signals can be generated in a vdW-layered semiconductor by introducing vanadium in ...

AI-driven muscle mass assessment could improve care for head and neck cancer patients

2023-08-10

Boston – Researchers from Dana-Farber Cancer Institute have found a way to use artificial intelligence (AI) to diagnose muscle wasting, called sarcopenia, in patients with head and neck cancer. AI provides a fast, automated, and accurate assessment that is too time-consuming and error-prone to be made by humans. The tool, published in JAMA Network Open, could be used by doctors to improve treatment and supportive care for patients.

“Sarcopenia is an indicator that the patient is not doing well. A real-time tool that tells us when a patient is losing muscle mass would trigger us to intervene and do something supportive ...

Alcohol consumption among adults with a cancer diagnosis

2023-08-10

About The Study: The findings of this study of 15,000 adults suggest that alcohol consumption and risky drinking behaviors were common among cancer survivors, even among individuals receiving treatment. Given the adverse treatment and oncologic outcomes associated with alcohol consumption, additional research and implementation studies are critical in addressing this emerging concern among cancer survivors.

Authors: Yin Cao, Sc.D., M.P.H., of the Washington University in St. Louis School of Medicine, is the corresponding author.

To ...

Five-year trajectories of prescription opioid use

2023-08-10

About The Study: The results of this study of 3.4 million adults suggest that most individuals commencing treatment with prescription opioids had relatively low and time-limited exposure to opioids over a 5-year period. The small proportion of individuals with sustained or increasing use was older with more comorbidities and use of psychotropic and other analgesic drugs, likely reflecting a higher prevalence of pain and treatment needs in these individuals.

Authors: Natasa Gisev, ...

A medication used for heart conditions improves the efficacy of current treatments for melanoma in mouse models

2023-08-10

The study, carried out by scientists from Navarrabiomed, the Institute of Neurosciences CSIC-UMH, and IRB Barcelona, has been published in Nature Metabolism.

In 2022, 7,500 new cases of melanoma—the most aggressive type of skin cancer—were diagnosed in Spain.

A collaborative study undertaken by the Navarrabiomed Biomedical Research Center (Pamplona, Navarre), the Institute of Neurosciences CSIC-UMH (Sant Joan d’Alacant, Valencian Community) and IRB Barcelona (Barcelona, Catalonia) shows that the administration of ranolazine, a drug currently used to treat heart conditions, improves the ...

Effectiveness of video gameplay restrictions questioned in new study

2023-08-10

Legal restrictions placed on the amount of time young people in China can play video games may be less effective than originally thought, a new study has revealed.

To investigate the effectiveness of the policy, a team of researchers led by the University of York, analysed over 7 billion hours of playtime data from tens of thousands of games, with data drawn from over two billion accounts from players in China, where legal restrictions on playtime for young people have been in place since 2019.

The research team, however, did not find evidence of a decrease in heavy play of games after these ...

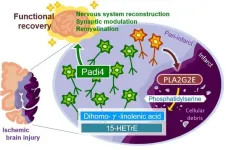

A new mechanism encouraging the brain to self-repair after an ischemic stroke

2023-08-10

Researchers from Tokyo Medical and Dental University (TMDU) identify lipids stimulating self-repair mechanisms in the brain after ischemic stroke

Tokyo, Japan – Patients often experience functional decline after an ischemic stroke, especially due to the brain’s resistance to regenerate after damage. Yet, there is still potential for recovery as surviving neurons can activate repair mechanisms to limit and even reverse the damage caused by the stroke. How is it triggered though?

In a study published ...

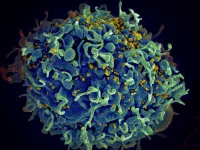

Researchers find new pathway for HIV invasion of cell nucleus

2023-08-10

The researchers also identified three proteins that are needed for the virus to carry out the invasion and have in turn synthesized molecules (potential drugs) that can target one of the proteins, potentially leading to new treatments for AIDS.

“We have revealed a protein pathway that appears to have a direct impact on diseases, which opens up a new area for potential drug development,” says the study’s senior author Aurelio Lorico, MD PhD, Professor of Pathology and interim Chief Research Officer at Touro University Nevada College of Osteopathic Medicine.

HIV infection requires the virus to enter a cell and gain access to the well-guarded nucleus in order ...

MSK Research Highlights, August 10, 2023

2023-08-10

New research from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK) and the Sloan Kettering Institute — a hub for basic science and translational research within MSK — found a potential target against neuroendocrine transformation in lung and prostate cancers; discovered new clues about why donor T cells attack certain tissues in graft-versus-host disease; shed light on why T cells let go of their prey; and used CRISPR interference and dynamic cell-state transitions to discover enhancers that affect early human development.

Targeting exportin 1 may help prevent neuroendocrine transformation in lung and prostate cancers

Over time, some lung and prostate ...