(Press-News.org) CHAPEL HILL, N.C. – Over the past decade, the gut microbiome has gained significant interest by scientists and non-scientists alike. Recent research has shown that the bacteria and other microbes in our gut play a supporting role in immunity, metabolism, digestion, and the fight against "bad bacteria" that try to invade our bodies.

However, new research published in Nature Biotechnology by Angela Wahl, PhD, Balfour Sartor, MD, J. Victor Garcia, PhD, and UNC School of Medicine colleagues others has revealed that the microbiome may not as always be protective against human pathogens.

Using a first-of-its-kind precision animal model with no microbiome (germ-free), researchers have shown that the microbiome has a significant impact on the acquisition of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV) infection and plays a role in the course of disease.

“These findings offer the first direct evidence that resident microbiota can have a significant impact on the establishment and pathology of infection by two different human-specific pathogens,” said Wahl, assistant professor in the Division of Infectious Diseases in the UNC Department of Medicine.

This research was conducted through a collaboration with scientists at the UNC International Center for the Advancement of Translational Science and the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology at the UNC School of Medicine.

For the discovery to be made, Wahl and Garcia needed to create a “humanized” mouse model that mimicked a human’s immune system to conduct their study. Once exposed to a virus, the humanized models can replicate the virus like a human and could be used for study.

But researchers needed to take it one step further. Wahl and Garcia needed to compare a conventional humanized mouse model to one without a microbiome (germ-free). This meant that they needed to create a first-of-its-kind mouse model that was humanized and free of bacteria.

Wahl, who is an expert in developing in-vivo models for human pathogens, and former UNC graduate student Morgan Chateau, PhD needed to figure out a way to humanize the animals while keeping them from encountering any germs, including those that live on our food, skin, in the air, or anywhere else in the external environment. To do so, they used a custom surgical isolation chamber, which is essentially a “big sterile bubble,” with specialized glove compartments and a microscope.

“This had never been done before,” said Wahl, who is also assistant director of the UNC International Center for the Advancement for Translational Science. “We humanized the mice and did our viral exposure experiments under strict germ-free conditions. Technically, it was very challenging.”

HIV is a retrovirus that primarily infects human CD4+ T cells and is mainly acquired through the GI tract. Rectal exposure, for example, in men who have sex with men accounts for more than half of new HIV infections. Breastfeeding is an example of an oral exposure that can also transmit HIV to infants.

Dr. Wenbo Yao, PhD, co-first author, found that rectal HIV acquisition was 200% higher in animals colonized with resident microbiome compared to germ-free animals. Similarly, oral HIV acquisition was 300% higher in animals colonized with resident microbiota compared to germ-free animals. Researchers also noticed that animals colonized with resident microbiota had HIV-RNA levels that were up to 34 times higher in plasma and more than 1,000 times higher in tissues than germ-free mice.

Co-author R. Balfour Sartor, MD, the Margaret and Lorimer W. Midget Distinguished Professor of Medicine in the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology and Department of Microbiology and Immunology, says that their innovative HIV findings may ultimately serve as a foundation from which other doctors and researchers can develop new clinical approaches and therapies.

“These findings open up a whole new door,” said Sartor, who also directs the National Gnotobiotic Rodent Resource Center that derived the germ- free mice. “Would it be possible to alter the gut microbiota, by decreasing the bacteria, fungi, and viruses that might increase expansion of the HIV infection? Or conversely, we could help patients build up microbes that would prevent that expansion and can work synergistically with antivirals to clear the HIV.”

Researchers then performed comparisons between colonized and germ-free animals, which revealed that the presence of resident microbiota increased the frequency of CCR5+CD4+ T cells, which are the main target of HIV infection throughout the gut. The findings suggest that enhanced HIV acquisition and replication is due to, at least in part, an increased density of target cells for local infection following oral or rectal HIV exposure.

“This is a finding of great significance,” said Wahl. “Everyone has a unique composition of microbes that colonize their gut. In the future, it will be important to evaluate how this diversity among people affects their risk for HIV acquisition and the subsequent course of disease.”

The findings on EBV were also important. EBV is a DNA herpesvirus that infects B cells and can cause mononucleosis. Almost 95% of the adult population harbors latent infection of EBV, but for some people with compromised immune systems, EBV infection can influence the development of certain types of cancers such as Hodgkin’s lymphoma, Non-Hodgkin lymphoma, Burkitt’s lymphoma and Nasopharyngeal carcinoma.

Wahl and Garcia found that mice with a normal microbiome that were exposed to EBV developed large macroscopic tumors in a variety of organs, including the spleen, liver, kidney, and stomach. These tumors were virtually absent in the germ-free mice infected with EBV. Future studies will be needed to evaluate the possible mechanism(s) for enhanced EBV infection and tumorigenesis in the presence of resident microbiota.

“We had two human pathogens that are different in every possible way,” said Garcia, who is director of the UNC International Center for the Advancement of Translational Science, Oliver Smithies Investigator and professor in the Departments of Medicine and Microbiology and Immunology. “The type of cell that they are infecting, the type of disease that they cause, the type of viruses that they are is completely different. Yet, the microbiome exacerbates the disease that each of those viruses causes.”

The researchers will now try to pinpoint the factors that determine whether the microbiome plays a role in the persistence of HIV and EBV infections throughout the body and figure out if the microbiome also affects other human-specific pathogens.

More specifically, Wahl, Garcia, and Sartor want to understand how the microbiome is contributing to HIV and EBV infections. They also want to identify which specific microbial strains are aiding in the viruses' capacity to replicate and cause disease and of particular importance which ones are protecting the host from the viruses. Sartor, in particular, is interested in learning if there are any additional latent viruses affected by the presence of the microbiome.

“Will the gut microbiome also influence reactivation of herpes simplex virus, shingles, and other latent viruses that cause tumors? We don't know, but there's a pretty good track record that microbes can influence certain bacterial and fungal pathogens. That may be something to explore as well.”

Wahl and Garcia hope that their findings will open a new area of exploration for researchers who are interested in the role of the microbiome on diseases caused by human specific pathogens.

“At the heart of all this is that we have created a new series of models that will allow investigators to ask questions they could never ask before,” said Garcia. “We have been able to do something that others thought could not be done.”

Other investigators include Joseph Pagano, MD, Craig Fletcher, DVM ,PhD, M. Andrea Azcarate-Peril, PhD, Michael Hudgens, PhD, Allison Rogala, DVM, and Joseph Tucker, MD, PhD from UNC, Christopher Whitehurst, PhD from New York Medical College, and Ian McGowan, MD, PhD from the University of Pittsburgh and Orion Biotechnology.

END

Gut microbiome can increase risk, severity of HIV, EBV disease

2023-08-10

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

YALE EMBARGOED NEWS: Yale scientists reveal two paths to autism in the developing brain

2023-08-10

New Haven, Conn. — Two distinct neurodevelopmental abnormalities that arise just weeks after the start of brain development have been associated with the emergence of autism spectrum disorder, according to a new Yale-led study in which researchers developed brain organoids from the stem cells of boys diagnosed with the disorder.

And, researchers say, the specific abnormalities seem to be dictated by the size of the child’s brain, a finding that could help doctors and researchers to diagnosis and treat autism in the future.

The findings were ...

Before reaching the skies, the Himalayas had a leg up, new study shows

2023-08-10

Mountain ranges play a key role in global climate, altering weather and shaping the flora and fauna that inhabit their slopes and the valleys below. As warm air rises windward grades and cools, moisture condenses into rain and snow. On the leeward side, it’s quite the opposite. Deserts prevail, a phenomenon known as rain shadow. Thus, the way mountain ranges form is a matter of intense interest among those who study and model climates of the past.

That debate will soon grow more heated with a new paper in the journal Nature Geoscience. A team of researchers ...

Scientists harness the power of AI to shed light on different types of Parkinson’s disease

2023-08-10

Francis Crick Institute press release

Under strict embargo: 16:00hrs BST 10 August 2023

Peer reviewed

Observational study

Cells

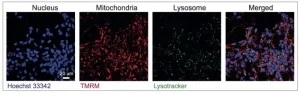

Researchers at the Francis Crick Institute and UCL Queen Square Institute of Neurology, working with technology company Faculty AI, have shown that machine learning can accurately predict subtypes of Parkinson’s disease using images of patient-derived stem cells.

Their work, published today in Nature Machine Intelligence, has shown that computer models can accurately classify four subtypes of Parkinson’s disease, with one reaching an accuracy of 95%. This could pave the way for personalised medicine and targeted drug discovery.

Parkinson’s ...

Researchers discover a potential application of unwanted electronic noise in semiconductors

2023-08-10

Random Telegraph Noise (RTN), a type of unwanted electronic noise, has long been a nuisance in electronic systems, causing fluctuations and errors in signal processing. However, a team of researchers from the Center for Integrated Nanostructure Physics within the Institute for Basic Science (IBS), South Korea has made an intriguing breakthrough that can potentially harness these fluctuations in semiconductors. Led by Professor LEE Young Hee, the team reported that magnetic fluctuations and their gigantic RTN signals can be generated in a vdW-layered semiconductor by introducing vanadium in ...

AI-driven muscle mass assessment could improve care for head and neck cancer patients

2023-08-10

Boston – Researchers from Dana-Farber Cancer Institute have found a way to use artificial intelligence (AI) to diagnose muscle wasting, called sarcopenia, in patients with head and neck cancer. AI provides a fast, automated, and accurate assessment that is too time-consuming and error-prone to be made by humans. The tool, published in JAMA Network Open, could be used by doctors to improve treatment and supportive care for patients.

“Sarcopenia is an indicator that the patient is not doing well. A real-time tool that tells us when a patient is losing muscle mass would trigger us to intervene and do something supportive ...

Alcohol consumption among adults with a cancer diagnosis

2023-08-10

About The Study: The findings of this study of 15,000 adults suggest that alcohol consumption and risky drinking behaviors were common among cancer survivors, even among individuals receiving treatment. Given the adverse treatment and oncologic outcomes associated with alcohol consumption, additional research and implementation studies are critical in addressing this emerging concern among cancer survivors.

Authors: Yin Cao, Sc.D., M.P.H., of the Washington University in St. Louis School of Medicine, is the corresponding author.

To ...

Five-year trajectories of prescription opioid use

2023-08-10

About The Study: The results of this study of 3.4 million adults suggest that most individuals commencing treatment with prescription opioids had relatively low and time-limited exposure to opioids over a 5-year period. The small proportion of individuals with sustained or increasing use was older with more comorbidities and use of psychotropic and other analgesic drugs, likely reflecting a higher prevalence of pain and treatment needs in these individuals.

Authors: Natasa Gisev, ...

A medication used for heart conditions improves the efficacy of current treatments for melanoma in mouse models

2023-08-10

The study, carried out by scientists from Navarrabiomed, the Institute of Neurosciences CSIC-UMH, and IRB Barcelona, has been published in Nature Metabolism.

In 2022, 7,500 new cases of melanoma—the most aggressive type of skin cancer—were diagnosed in Spain.

A collaborative study undertaken by the Navarrabiomed Biomedical Research Center (Pamplona, Navarre), the Institute of Neurosciences CSIC-UMH (Sant Joan d’Alacant, Valencian Community) and IRB Barcelona (Barcelona, Catalonia) shows that the administration of ranolazine, a drug currently used to treat heart conditions, improves the ...

Effectiveness of video gameplay restrictions questioned in new study

2023-08-10

Legal restrictions placed on the amount of time young people in China can play video games may be less effective than originally thought, a new study has revealed.

To investigate the effectiveness of the policy, a team of researchers led by the University of York, analysed over 7 billion hours of playtime data from tens of thousands of games, with data drawn from over two billion accounts from players in China, where legal restrictions on playtime for young people have been in place since 2019.

The research team, however, did not find evidence of a decrease in heavy play of games after these ...

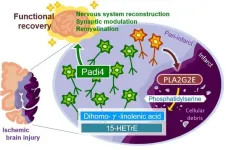

A new mechanism encouraging the brain to self-repair after an ischemic stroke

2023-08-10

Researchers from Tokyo Medical and Dental University (TMDU) identify lipids stimulating self-repair mechanisms in the brain after ischemic stroke

Tokyo, Japan – Patients often experience functional decline after an ischemic stroke, especially due to the brain’s resistance to regenerate after damage. Yet, there is still potential for recovery as surviving neurons can activate repair mechanisms to limit and even reverse the damage caused by the stroke. How is it triggered though?

In a study published ...