(Press-News.org) PHILADELPHIA – Lou Gehrig's disease, or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) are characterized by protein clumps in brain and spinal-cord cells that include an RNA-binding protein called TDP-43. This protein is the major building block of the lesions formed by these clumps.

In a study published in the Journal of Clinical Investigation, a team led by Virginia M.-Y. Lee, PhD, director of Penn's Center for Neurodegenerative Disease Research, describes the first direct evidence of how mutated TDP-43 can cause neurons to die. Although normally found in the nucleus where it regulates gene expression, TDP-43 was first discovered in 2006 to be the major disease protein in ALS and FTLD by the Penn team led by Lee and John Q. Trojanowski, MD, PhD, director of the Institute on Aging at Penn. This discovery has transformed research on ALS and FTLD by linking them to the same disease protein.

"The discovery of TDP-43 as the pathological link between mechanisms of nervous system degeneration in both ALS and FTLD opened up new opportunities for drug discovery as well as biomarker development for these disorders," says Lee. "An animal model of TDP-43-mediated disease similar to ALS and FTLD will accelerate these efforts."

In the case of TDP-43, neurons could die for two reasons: One, the clumps themselves are toxic to neurons or, two, when TDP-43 is bound up in clumps outside the nucleus, it depletes the cell of normally functioning TDP-43. Normally a cell regulates the exact amount of TDP-43 in itself -- too much is bad and too little is also bad. The loss of function of TDP-43 is important in regulating disease because it regulates gene expression.

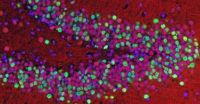

To determine the effects of misplaced TDP-43 on the viability of neurons, the researchers made transgenic mice expressing human mutated TDP-43 in the cytoplasm and compared them to mice expressing normal human TDP-43 in the nucleus of nerve cells. Expression of either human TDP-43 led to neuron loss in vulnerable forebrain regions; degeneration of part of the spinal cord tract; and muscle spasms in the mice. These effects recapitulate key aspects of FTLD and a subtype of ALS known as primary lateral sclerosis.

The JCI study showed that a dramatic loss of function causes nerve-cell death because normal mouse TDP-43 is eliminated when human mutated TDP-43 genes are put into the mice. Since cells regulate the exact amount of TDP-43, over-expression of the human TDP-43 protein prevents the mouse TDP-43 from functioning normally. Lee and colleagues think this effect leads to neuron death rather than clumps of TDP-43 because these clumps were rare in the mouse cells observed in this study. Lee says that it is not yet clear why clumps were rare in this mouse model when they are so prevalent in human post-mortem brain tissue of ALS and FTLD patients.

Neurodegeneration in the mouse neurons expressing TDP-43 -- both the normal and mutated human versions -- was accompanied by a dramatic downregulation of the TDP-43 protein mice are born with. What's more, mice expressing the mutated human TDP-43 exhibited profound changes in gene expression in neurons of the brain's cortex.

The findings suggest that disturbing the normal TDP-43 in the cell nucleus results in loss of normal TDP-43 function and gene regulatory pathways, culminating in degeneration of affected neurons.

Next steps, say the researchers, will be to look for the specific genes that are regulated by TDP-43 and how mRNA splicing is involved so that the abnormal regulation of these genes can be corrected.

At the same time, notes Lee, "We soon will launch studies of novel strategies to prevent TDP-43-mediated nervous system degeneration using this mouse model of ALS and FTLD."

INFORMATION:

The study was funded in part by funds from the National Institutes of Health.

Penn Medicine is one of the world's leading academic medical centers, dedicated to the related missions of medical education, biomedical research, and excellence in patient care. Penn Medicine consists of the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine (founded in 1765 as the nation's first medical school) and the University of Pennsylvania Health System, which together form a $3.6 billion enterprise.

Penn's School of Medicine is currently ranked #2 in U.S. News & World Report's survey of research-oriented medical schools, and is consistently among the nation's top recipients of funding from the National Institutes of Health, with $367.2 million awarded in the 2008 fiscal year.

Penn Medicine's patient care facilities include:

The Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania – the nation's first teaching hospital, recognized as one of the nation's top 10 hospitals by U.S. News & World Report.

Penn Presbyterian Medical Center – named one of the top 100 hospitals for cardiovascular care by Thomson Reuters for six years.

Pennsylvania Hospital – the nation's first hospital, founded in 1751, nationally recognized for excellence in orthopaedics, obstetrics & gynecology, and psychiatry & behavioral health.

Additional patient care facilities and services include Penn Medicine at Rittenhouse, a Philadelphia campus offering inpatient rehabilitation and outpatient care in many specialties; as well as a primary care provider network; a faculty practice plan; home care and hospice services; and several multispecialty outpatient facilities across the Philadelphia region.

Penn Medicine is committed to improving lives and health through a variety of community-based programs and activities. In fiscal year 2009, Penn Medicine provided $733.5 million to benefit our community.

Malfunctioning gene associated with Lou Gehrig's disease leads to nerve-cell death in mice

2011-01-06

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Syracuse University team develops functionally graded shape memory polymers

2011-01-06

A team led by Patrick T. Mather, director of Syracuse Biomaterials Institute (SBI) and Milton and Ann Stevenson professor of biomedical and chemical engineering in Syracuse University's L.C. Smith College of Engineering and Computer Science (LCS), has succeeded in applying the concept of functionally graded materials (FGMs) to shape memory polymers (SMPs).

SMPs are a class of "smart" materials that can switch between two shapes, from a fixed (temporary) shape to a predetermined permanent shape. Shape memory polymers function as actuators, by first forming a heated article ...

Widespread ancient ocean 'dead zones' challenged early life

2011-01-06

The oceans became oxygen-rich as they are today about 600 million years ago, during Earth's Late Ediacaran Period. Before that, most scientists believed until recently, the ancient oceans were relatively oxygen-poor for the preceding four billion years.

Now biogeochemists at the University of California-Riverside (UCR) have found evidence that the oceans went back to being "anoxic," or oxygen-poor, around 499 million years ago, soon after the first appearance of animals on the planet.

They remained anoxic for two to four million years.

The researchers suggest that ...

Newly developed cloak hides underwater objects from sonar

2011-01-06

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — In one University of Illinois lab, invisibility is a matter of now you hear it, now you don't.

Led by mechanical science and engineering professor Nicholas Fang, Illinois researchers have demonstrated an acoustic cloak, a technology that renders underwater objects invisible to sonar and other ultrasound waves.

"We are not talking about science fiction. We are talking about controlling sound waves by bending and twisting them in a designer space," said Fang, who also is affiliated with the Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology. "This ...

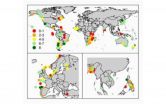

Globally sustainable fisheries possible with co-management

2011-01-06

The bulk of the world's fisheries--including the kind of small-scale, often non-industrialized fisheries that millions of people depend on for food--could be sustained using community-based co-management. This is the conclusion of a study reported in this week's issue of the journal Nature.

"The majority of the world's fisheries are not--and never will be--managed by strong centralized governments with top-down rules and the means to enforce them," says Nicolas Gutiérrez, a University of Washington fisheries scientist and lead author of the Nature paper.

"Our findings ...

Violence against mothers linked to 1.8 million female infant and child deaths in India

2011-01-06

Boston, MA -- The deaths of 1.8 million female infants and children in India over the past 20 years are related to domestic violence against their mothers, according to a new study led by researchers at the Harvard School of Public Health (HSPH). In their examination of over 158,000 births occurring between 1985 and 2005, the researchers found that husbands' violence against wives increased the risk of death among female children, but not male children, in both the first year and the first five years of life.

"Being born a girl into a family in India in which your mother ...

Mayo Clinic determines lifetime risk of adult rheumatoid arthritis

2011-01-06

ROCHESTER, Minn. -- Mayo Clinic researchers have determined the lifetime risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis and six other autoimmune rheumatic diseases for both men and women. The findings appear online in Arthritis and Rheumatism.

VIDEO ALERT: Additional audio and video resources, including excerpts from an interview with Cynthia Crowson describing the research, are available on the Mayo Clinic News Blog(http://newsblog.mayoclinic.org/2011/01/05/whats-your-risk-of-developing-rheumatoid-arthritis/)

"We estimated the lifetime risk for rheumatic disease for both ...

Consumers prefer products with few, and mostly matching, colors

2011-01-06

COLUMBUS, Ohio – Most people like to play it safe when combining colors for an article of clothing or outfit, a new study suggests.

When consumers were asked to choose colors for seven different parts of an athletic shoe, they tended to pick identical or similar colors for nearly every element.

They usually avoided contrasting or even moderately different color combinations.

A red and yellow athletic shoe? Not going to happen. Blue and grey? That's more like it.

This is one of the first studies to show how consumers would choose to combine colors in a realistic ...

Major advance in MRI allows much faster brain scans

2011-01-06

An international team of physicists and neuroscientists has reported a breakthrough in magnetic resonance imaging that allows brain scans more than seven times faster than currently possible.

In a paper that appeared Dec. 20 in the journal PLoS ONE, a University of California, Berkeley, physicist and colleagues from the University of Minnesota and Oxford University in the United Kingdom describe two improvements that allow full three-dimensional brain scans in less than half a second, instead of the typical 2 to 3 seconds.

"When we made the first images, it was unbelievable ...

UConn cardiologists uncover new heart attack warning sign

2011-01-06

Cardiologists at the University of Connecticut Health Center have identified a protein fragment that when detected in the blood can be a predictor of heart attack.

Their research, led by Dr. Bruce Liang, director of the Pat and Jim Calhoun Cardiology Center, is published in the Jan. 11 issue of the Journal of the American College of Cardiology. It found heart attack patients had elevated levels of the protein fragment known as Caspase-3 p17 in their blood.

"We've discovered a new biomarker for heart attack, and showed that apoptosis, or a particular kind of cell death, ...

Scientists now know why some cancers become malignant and others don't

2011-01-06

Cancer cells reproduce by dividing in two, but a molecule known as PML limits how many times this can happen, according to researchers lead by Dr. Gerardo Ferbeyre of the University of Montreal's Department of Biochemistry. The team proved that malignant cancers have problems with this molecule, meaning that in its absence they can continue to grow and eventually spread to other organs. Importantly, the presence of PML molecules can easily be detected, and could serve to diagnose whether a tumor is malignant or not.

"We discovered that benign cancer cells produce the ...