(Press-News.org) The virulence of a rice-wrecking fungus — and deployment of ninja-like proteins that help it escape detection by muffling an immune system’s alarm bells — relies on genetic decoding quirks that could prove central to stopping it, says research from the University of Nebraska–Lincoln.

A Nebraska team helmed by Richard Wilson hopes that identifying an essential but formerly unknown stage in the fungal takeover of rice cells can accelerate the treatment or prevention of rice blast disease, which ruins up to 30% of global yields each year.

“The response I’ve gotten from people in my field is that they’re very excited, because nobody’s been able to get a handle on this,” said Wilson, professor of plant pathology at Nebraska.

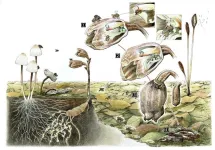

Most cellular machines, or proteins, are secreted in the same way: After being constructed and folded into their near-final forms at the endoplasmic reticulum, they move on to the Golgi body, which packages and forwards them along to their ultimate destinations. But certain proteins will bypass the Golgi body in favor of unconventional, poorly understood pathways. Wilson’s team has now shown that one of those unconventional pathways involves modifying not the secreted protein itself, but the genetic code of a molecule that aids in its construction.

Known as transfer RNA, or tRNA, that molecule hauls around amino acids — the building blocks of every protein — in search of a blueprint that calls for its particular cargo. Those blueprints exist as three-letter codes, or codons, carried by the fittingly named messenger RNA. When a tRNA comes across and decodes an mRNA whose codon matches its own three-letter combination, it unloads its corresponding amino acid, adding it to a string of others that ultimately yield a finished protein.

Before giving up their precious cargo, though, some tRNAs undergo chemical makeovers. One especially notable modification? The addition of sulfur to the tRNA’s third letter, or nucleotide — specifically when that letter is U, the nucleotide known as uridine. Though that sulfur addition has been conserved and observed in a wide range of organisms, from yeast to mice to humans, researchers have yet to pin down all its functions.

Wilson and his colleagues decided to play an educated hunch: that the modification of the tRNA’s uridine might prove important to the growth of Magnaporthe oryzae, the fungal species that causes rice blast disease. To test its importance, the researchers resorted to the tried-and-true method of removing the genes responsible for the modification, then looking for any differences between that mutant fungus and its original counterpart.

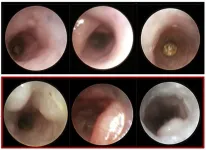

The team discovered even more than it bargained for. Gone were some of the ninja-like proteins, or effectors, that are secreted via the unconventional pathway before infiltrating the cytoplasm of rice cells to mitigate their innate immune responses. And when the team deposited spores from the mutant M. oryzae on rice seedlings, the effector-less fungus mustered only minuscule lesions on their leaves — lesions far smaller than those managed by the untouched, virulent fungus.

That sulfur-modified tRNA could assist the search for disease-enabling effectors in M. oryzae and a rash of other pathogens, Wilson said. In the case of M. oryzae, tRNAs were consistently matching with mRNA codons ending in AA — adenine in the second and third positions of the codon. Yet the team knew that other tRNAs could also match with synonymous codons that instead ended in AG, unloading the very same amino acid when they did — and without the fuss of adding sulfur beforehand. Which left a question: Why, exactly, did M. oryzae prefer the AA-ending codons to their AG-ending peers?

Another experiment would help solve the mystery. Swapping out the AA-ending codons for AG, the team found, did lead the M. oryzae to resume its production of the virulent effector proteins. Unfortunately for the fungus, it began cranking out so many effectors that they effectively disrupted their own stealth operation and ultimately failed to facilitate infection, the result of far too many cooks in a nanoscopic kitchen. The AA-ending codons, it turned out, were not only enabling but also regulating the production of the effectors. It was clear: The stealthy proteins depended on both the sulfur modification and one specific, calibrating type of codon being targeted by it. If either was missing, the whole gambit fell apart.

Because mRNA extracts its blueprints directly from the source code known as DNA, analyzing the latter can allow researchers to discern the presence and prevalence of codons in the former. Knowing just how heavily M. oryzae depends on AA-ending codons to churn out the effectors that invade a rice cell’s cytoplasm, Wilson and his colleagues went looking for signs of them in relevant genes. The team was not disappointed: In one case study, more than 90% of the AG- and AA-ending codons for a cytoplasmic effector fell into the latter category.

Researchers could easily seek out the same telltale disparity for the sake of tracking down more effectors — whether in fungus or other pathogenic organisms — that perpetuate sneak attacks, Wilson said.

“One of the goals of plant pathology is to identify new effectors and figure out their functions, which are often to inhibit the function of some plant protein or evade detection,” he said. “And then, if you find that target in the plant, you can make changes in the plant to make them more resistant. So finding effectors is really a search for durable plant disease resistance.

“I think, in the near term, we’ll use this to leverage more of an understanding of this unconventional secretion pathway. It’s the only pathway known for the blast fungus to get effectors into a plant cell, so if you can inhibit it in some way, then it would really be detrimental to the fungus in terms of being able to cause disease.”

An acclaimed cellular biologist not involved in the study compared the team’s achievement to that of Bob Beamon, who sailed nearly 2 feet past the then-world record in the long jump at the 1968 Summer Olympics.

“This work is not just an step forward towards understanding the role of unconventional secretion in fungal pathogenicity to plants, it is a long leap, comparable to Bob Beamon’s 890 cm in Mexico 68,” Miguel Peñalva wrote on the X platform, formerly known as Twitter.

The unconventional effector pathway studied by the team encompasses more than just the kingdoms of fungi and plants, Wilson said. Parasitic protists that drive many human-contracted diseases, including malaria, secrete immune-snuffing proteins in much the same way as M. oryzae. Some cancer cells also use the pathway. Ideally, Wilson said the team’s study could inform efforts to both identify new effectors and understand why they emerged as weapons of choice against human cells, too.

“So there are many ways,” he said, “in which this work could enlighten a whole host of things.”

The researchers reported their findings in the journal Nature Microbiology. Richards authored the study with Gang Li and Nawaraj Dulal, both with Nebraska’s Department of Plant Pathology, alongside Ziwen Gong of the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences. The team received support in part from the National Science Foundation.

END

Study IDs secret of stealthy invader essential to ruinous rice disease

Findings could inform treatment of pathogens common in plants, people

2023-08-24

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Mutations in blood stem cells can exacerbate colon cancer

2023-08-24

Researchers at the University of Florida College of Medicine have discovered how common age-related changes in the blood system can make certain colon cancers grow faster. The study, to be published August 24 in the Journal of Experimental Medicine (JEM), also suggests how these effects might be therapeutically targeted to reduce tumor growth and improve patient survival.

As we age, the hematopoietic stem cells that reside in the bone marrow and give rise to all of the body’s different blood cells gradually acquire mutations in their ...

The ‘treadmill conveyor belt’ ensuring proper cell division

2023-08-24

Researchers at the Centre for Genomic Regulation (CRG) have discovered how proteins work in tandem to regulate ‘treadmilling’, a mechanism used by the network of microtubules inside cells to ensure proper cell division. The findings are published today in the Journal of Cell Biology.

Microtubules are long tubes made of proteins that serve as infrastructure to connect different regions inside of a cell. Microtubules are also critical for cell division, where they are key components of the spindle, the structure which attaches itself to chromosomes and pulls them apart into each new cell.

For the spindle to function properly, cells rely on microtubules to ‘treadmill’. ...

Significant progress in cell separation technology made by Griffith University team

2023-08-24

Early detection allows for timely intervention in many diseases before they progress to a severe stage, often at a lower treatment cost. This is particularly crucial in the case of cancer, as the stage of cancer development at the time of initial diagnosis significantly influences the patient's prognosis and survival rate. Therefore, regular medical check-ups can ensure better survival and quality of life. However, the multitude of medical examination items makes the experience both loved and loathed. With various ...

Fungi-eating plants and flies team up for reproduction

2023-08-24

Fungi-eating orchids were found for the first time to offer their flowers to fungi-eating fruit flies in exchange for pollination, which is the first evidence for nursery pollination in orchids. This unique new plant-animal relationship hints at an evolutionary transition towards mutualistic symbiosis.

Orchids are well known to trick their pollinators into visiting the flowers by imitating food sources, breeding grounds or even mates without actually offering anything in return. The fungi-eating, non-photosynthetic orchid genus Gastrodia is no different: To attract fruit flies (Drosophila spp.), the plants usually emits a smell like their common diet of fermented fruits ...

Preterm babies given certain fatty acids have better vision

2023-08-24

Preterm babies given a supplement with a combination of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids have better visual function by the age of two and a half. This has been shown by a study at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden.

The study, published in The Lancet Regional Health Europe, covers 178 extremely preterm babies at the neonatal units of the university hospitals in Gothenburg, Lund, and Stockholm between 2016 and 2019. Extremely preterm babies are those born before the 28th week of pregnancy.

Around half of the children were given preventive oral nutritional supplements containing the omega-6 fatty acid AA (arachidonic acid) and the omega-3 fatty acid DHA (docosahexaenoic ...

Manchester research to boost bioprinting technology to address critical health challenges in space

2023-08-24

New research by The University of Manchester will enhance the power of bioprinting technology, opening doors to transform advances in medicine and addressing critical health challenges faced by astronauts during space missions.

Bioprinting involves using specialised 3D printers to print living cells creating new skin, bone, tissue or organs for transplantation.

The technique has the potential to revolutionise medicine, and specifically in the realm of space travel, bioprinting could have a significant impact.

Astronauts on extended space missions have ...

Social media does not cause depression in children and young people

2023-08-24

“The prevalence of anxiety and depression has increased. As has the use of social media. Many people therefore believe that there has to be a correlation,” says Silje Steinsbekk, a professor at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology's (NTNU) Department of Psychology.

But that is not the case if we are to believe the results of the study “Social media behaviours and symptoms of anxiety and depression. A four-wave cohort study from age 10-16 years”.

Trondheim Early Secure Study

In the Trondheim Early Secure Study research project, researchers followed 800 children in Trondheim ...

Researchers reveal electronic nematicity without charge density waves in titanium-based kagome metal

2023-08-24

Chestnut Hill, Mass (8/24/2023) – Electronic nematic order in kagome materials has thus far been entangled with charge density waves. Now it is finally observed as a stand-alone phase in a titanium-based Kagome metal, a team of researchers led by Boston College physicists reported recently in Nature Physics.

Quantum materials composed of atoms arranged on a kagome net of corner-sharing triangles present an exciting platform to realize novel electronic behavior, paper co-author and Boston College Professor of Physics Ilija Zeljkovic explained.

There ...

Mount Sinai researchers find Asian Americans to have significantly higher exposure to “toxic forever” chemicals

2023-08-24

New York, NY (August 24, 2023) — Asian Americans have significantly higher exposure than other ethnic or racial groups to PFAS, a family of thousands of synthetic chemicals also known as “toxic forever” chemicals, Mount Sinai-led researchers report.

People frequently encounter PFAS (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances) in everyday life, and these exposures carry potentially adverse health impacts, according to the study published in Environmental Science and Technology, in the special issue “Data Science for Advancing Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology.”

The ...

Stormwater biofiltration increases coho salmon hatchling survival

2023-08-24

PUYALLUP, Wash. – A relatively simple, inexpensive method of filtering urban stormwater runoff dramatically boosted survival of newly hatched coho salmon in an experimental study. That’s the good news for the threatened species from the Washington State University-led research. The bad news: unfiltered stormwater killed almost all of them.

The findings, published in the journal Science of the Total Environment, are consistent with previous research on adult and juvenile coho that found exposure to untreated roadway runoff that typically winds up ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Scientists deliver new molecule for getting DNA into cells

Study reveals insights about brain regions linked to OCD, informing potential treatments

Does ocean saltiness influence El Niño?

2026 Young Investigators: ONR celebrates new talent tackling warfighter challenges

Genetics help explain who gets the ‘telltale tingle’ from music, art and literature

Many Americans misunderstand medical aid in dying laws

Researchers publish landmark infectious disease study in ‘Science’

New NSF award supports innovative role-playing game approach to strengthening research security in academia

Kumar named to ACMA Emerging Leaders Program for 2026

AI language models could transform aquatic environmental risk assessment

New isotope tools reveal hidden pathways reshaping the global nitrogen cycle

Study reveals how antibiotic structure controls removal from water using biochar

Why chronic pain lasts longer in women: Immune cells offer clues

Toxic exposure creates epigenetic disease risk over 20 generations

More time spent on social media linked to steroid use intentions among boys and men

New study suggests a “kick it while it’s down” approach to cancer treatment could improve cure rates

Milken Institute, Ann Theodore Foundation launch new grant to support clinical trial for potential sarcoidosis treatment

New strategies boost effectiveness of CAR-NK therapy against cancer

Study: Adolescent cannabis use linked to doubling risk of psychotic and bipolar disorders

Invisible harms: drug-related deaths spike after hurricanes and tropical storms

Adolescent cannabis use and risk of psychotic, bipolar, depressive, and anxiety disorders

Anxiety, depression, and care barriers in adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities

Study: Anxiety, gloom often accompany intellectual deficits

Massage Therapy Foundation awards $300,000 research grant to the University of Denver

Gastrointestinal toxicity linked to targeted cancer therapies in the United States

Countdown to the Bial Award in Biomedicine 2025

Blood marker from dementia research could help track aging across the animal world

Birds change altitude to survive epic journeys across deserts and seas

Here's why you need a backup for the map on your phone

ACS Central Science | Researchers from Insilico Medicine and Lilly publish foundational vision for fully autonomous “Prompt-to-Drug” pharmaceutical R&D

[Press-News.org] Study IDs secret of stealthy invader essential to ruinous rice diseaseFindings could inform treatment of pathogens common in plants, people