(Press-News.org)

How a new method of inferring ancient population size revealed a severe bottleneck in the human population which almost wiped out the chance for humanity as we know it today.

An unexplained gap in the African/Eurasian fossil record may now be explained thanks to a team of researchers from China, Italy and the United States. Using a novel method called FitCoal (fast infinitesimal time coalescent process), the researchers were able to accurately determine demographic inferences by using modern-day human genomic sequences from 3,154 individuals. These findings indicate that early human ancestors went through a prolonged, severe bottleneck in which approximately 1,280 breeding individuals were able to sustain a population for about 117,000 years. While this research has illuminated some aspects of early to middle Pleistocene ancestors, there are many more questions to be answered since uncovering this information.

A large amount of genomic sequences were analyzed in this study. However, “the fact that FitCoal can detect the ancient severe bottleneck with even a few sequences represents a breakthrough,” says senior author Yun-Xin Fu, a theoretical population geneticist at University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston.

Researchers will publish their findings online in Science on August 31, 2023 (America Eastern Standard Time). The results determined using FitCoal to calculate the likelihood for present-day genome sequences found that early human ancestors experienced extreme loss of life and therefore, loss of genetic diversity.

“The gap in the African and Eurasian fossil records can be explained by this bottleneck in the Early Stone Age as chronologically. It coincides with this proposed time period of significant loss of fossil evidence,” says senior author Giorgio Manzi, an anthropologist at Sapienza University of Rome. Reasons suggested for this downturn in human ancestral population are mostly climatic: glaciation events around this time lead to changes in temperatures, severe droughts, and loss of other species, potentially used as food sources for ancestral humans.

An estimated 65.85% of current genetic diversity may have been lost due to this bottleneck in the early to middle Pleistocene era, and the prolonged period of minimal numbers of breeding individuals threatened humanity as we know it today. However, this bottleneck seems to have contributed to a speciation event where two ancestral chromosomes may have converged to form what is currently known as chromosome 2 in modern humans. With this information, the last common ancestor has potentially been uncovered for the Denisovans, Neanderthals, and modern humans (Homo sapiens).

We all know that once a question is answered, more questions arise.

“The novel finding opens a new field in human evolution because it evokes many questions, such as the places where these individuals lived, how they overcame the catastrophic climate changes, and whether natural selection during the bottleneck has accelerated the evolution of human brain,” says senior author Yi-Hsuan Pan, an evolutionary and functional genomics at East China Normal University (ECNU).

Now that there is reason to believe an ancestral struggle occurred between 930,000 and 813,000 years ago, researchers can continue digging to find answers to these questions and reveal how such a small population persisted in assumably tricky and dangerous conditions. The control of fire, as well as the climate shifting to be more hospitable for human life, could have contributed to a later rapid population increase around 813,000 years ago.

“These findings are just the start. Future goals with this knowledge aim to paint a more complete picture of human evolution during this Early to Middle Pleistocene transition period, which will in turn continue to unravel the mystery that is early human ancestry and evolution,” says senior author LI Haipeng, a theoretical population geneticist and computational biologist at Shanghai Institute of Nutrition and Health, Chinese Academy of Sciences (SINH-CAS).

This research was jointly led by LI Haipeng at SINH-CAS and Yi-Hsuan Pan at ECNU. Their collaborators, Fabio Di Vincenzo at the University of Florence, Giogio Manzi at Sapienza University of Rome, and Yun-Xin Fu at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, have made important contribution to the findings. The research was first-authored by HU Wangjie and HAO Ziqian who used to be students/interns at SINH-CAS and ECNU. They are currently affiliated with Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, and Shandong First Medical University & Shandong Academy of Medical Sciences, respectively. DU Pengyuan at SINH-CAS, and CUI Jialong at ECNU also contributed to this research.

END

Between 800,000 and 900,000 years ago, the population of human ancestors crashed, according to a new genomic model by Wangjie Hu and colleagues. They suggest that there were only about 1280 breeding individuals during this transition between the early and middle Pleistocene, and that the population bottleneck lasted for about 117,000 years. The researchers say about 98.7% of the ancestral population was lost at the beginning of the bottleneck. This decline coincided with climate changes that turned glaciations into long-term events, a decrease ...

A randomized trial involving 811 undergraduate students at a U.S. Hispanic-Serving Institution (HIS) university found that students assigned to calculus classes focused on collaborative learning and student engagement had a greater understanding of calculus concepts and improved grades compared to those assigned to classes taught in a traditional lecture style. Laird Kramer and colleagues note that the success of the engagement “treatment” occurred across all racial and ethnic groups, academic majors, and genders. Since ...

A new estimate of the genetic mutation rate in four wild species of baleen whales suggests that these rates are higher than previous estimates, with some interesting implications for calculations of past whale abundance and low cancer rates. For instance, the new mutation rate determined by Marcos Suárez-Menéndez and colleagues reduces estimates of abundance in pre-exploitation whale populations by 86%, which has implications for population-rebuilding goals of whale conservation programs. The mutation rate—the probability ...

This release has been removed per the request of the submitting PIO. END ...

Polysiloxanes, the scientific name for silicones, possess exceptional properties, and are used in numerous fields ranging from cosmetics to aerospace. They are absolutely everywhere! However, they have a major flaw, as small, cyclic oligosolixanes—toxic for the environment and identified as an endocrine disruptor—form during their synthesis. To correct this drawback, a team of scientists1 led by a CNRS researcher recently developed a new process for synthesising silicones in a cleaner and more environmentally-friendly ...

New research from the University of Washington and Polar Bears International in Bozeman, Montana, quantifies the relationship between greenhouse gas emissions and the survival of polar bear populations. The paper, published online Aug. 31 in Science, combines past research and new analysis to provide a quantitative link between greenhouse gas emissions and polar bear survival rates.

A warming Arctic is limiting polar bears’ access to sea ice, which the bears use as a hunting platform. In ice-free summer months the bears must fast. While in a worst-case scenario ...

Exciting a brain region using electrical noise stimulation can help improve mathematical learning in those who struggle with the subject, according to a new study from the Universities of Surrey and Oxford, Loughborough University, and Radboud University in The Netherlands.

During this unique study, researchers investigated the impact of neurostimulation on learning. Despite the growing interest in this non-invasive technique, little is known about the neurophysiological changes induced and the effect it has on learning.

Researchers found that electrical noise ...

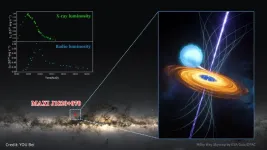

An international scientific team has revealed for the first time the magnetic field transport processes in the accretion flow of a black hole and the formation of a "MAD"—a magnetically arrested disk—in the vicinity of a black hole.

The researchers made the discovery while conducting multi-wavelength observational studies of an outburst event of the black hole X-ray binary MAXI J1820+070, using Insight-HXMT, China's first X-ray astronomical satellite, as well as multiple telescopes.

Key to their discovery was the observation that the radio emission from the black hole jet and the optical emission from the outer ...

An international team of marine scientists, led by the University of Groningen in the Netherlands and the Center for Coastal Studies in the USA, has studied the DNA of family groups from four different whale species to estimate their mutation rates. The results revealed much higher mutation rates than previously thought, and which are similar to those of smaller mammals such as humans, apes, and dolphins. Using the newly determined rates, the group found that the number of humpback whales in the North Atlantic before whaling was 86 percent lower than earlier studies suggested. The study is the first proof that this method can be used to estimate mutation rates ...

Researchers at University of Manchester and the École polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), Switzerland, have revealed an innovative approach to track individual molecule dynamics within nanofluidic structures, illuminating their response to molecules in ways never before possible.

Nanofluidics, the study of fluids confined within ultra-small spaces, offers insights into the behaviour of liquids on a nanometer scale. However, exploring the movement of individual molecules in such confined environments has been challenging due to the limitations of conventional microscopy techniques. This obstacle prevented ...