(Press-News.org) Right at the bottom of the deep sea, the first very simple forms of life on earth probably emerged a long time ago. Today, the deep sea is known for its bizarre fauna. Intensive research is being conducted into how the number of species living on the sea floor have changed in the meantime. Some theories say that the ecosystems of the deep sea have emerged again and again after multiple mass extinctions and oceanic upheavals. Today's life in the deep sea would thus be comparatively young in the history of the Earth. But there is increasing evidence that parts of this world are much older than previously thought. A research team led by the University of Göttingen has now provided the first fossil evidence for a stable colonisation of the deep sea floor by higher invertebrates for at least 104 million years. Fossil spines of irregular echinoids (sea urchins) indicate their long-standing existence since the Cretaceous period, as well as their evolution under the influence of fluctuating environmental conditions. The results have been published in the journal PLOS ONE.

The researchers examined over 1,400 sediment samples from boreholes in the Pacific, Atlantic and Southern Ocean representing former water depths of 200 to 4,700 metres. They found more than 40,000 fragments of spines, which they assigned to a group called irregular echinoids, based on their structure and shape. For comparison, the scientists recorded morphological characteristics of the spines, such as shape and length, and determined the thickness of around 170 spines from each of two time periods. As an indicator of the total mass of the sea urchins in the habitat – their biomass – they determined the amount of spiny material in the sediments.

What these fossil spines document is that the deep sea has been continuously populated by irregular echinoids since at least the early Cretaceous period about 104 million years ago. And they provide further exciting insights into the past: the devastating meteorite impact at the end of the Cretaceous period about 66 million years ago, which resulted in a worldwide mass extinction – with the dinosaurs as the most prominent victims – also caused considerable disturbances in the deep sea. This is shown by the morphological changes in the spines: they were thinner and less diverse in shape after the event than before. The researchers interpret this as the “Lilliput Effect”. This means that smaller species have a survival advantage after a mass extinction, leading to the smaller body size of a species. The cause could have been the lack of food at the bottom of the deep sea.

"We interpret the changes in the spines as an indication of the constant evolution and emergence of new species in the deep sea," explains Dr Frank Wiese from the Department of Geobiology at the University of Göttingen, the lead author of the study. He emphasises another finding: "About 70 million years ago, the biomass of sea urchins increased. We know that the water cooled down at the same time. This relationship between biomass in the deep sea and water temperature allows us to speculate how the deep sea will change due to human-induced global warming."

In addition to the University of Göttingen, the Universities of Heidelberg and Frankfurt as well as the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin were involved in the research project.

Original publication: Frank Wiese et al. A 104-Ma record of deep-sea Atelostomata (Holasterioda, Spatangoida, irregular echinoids) – a story of persistence, food availability and a big bang. PLOS ONE (2023). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0288046

Contact:

Dr Frank Wiese

University of Göttingen

Faculty of Earth Sciences and Geography

Geosciences Centre

Department of Geobiology

Goldschmidtstraße 3, 37077 Göttingen, Germany

Tel: +49 (0)176 29320024

Email: fwiese1@gwdg.de

END

Fossil spines reveal deep sea’s past

Research team led by Göttingen University describe early occurrence of irregular sea urchins in the depths of the oceans

2023-09-05

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

MSU researchers discover link between cholesterol and diabetic retinopathy

2023-09-05

Images

EAST LANSING, Mich. – Advancements that could lead to earlier diagnosis and treatment for diabetic retinopathy, a common complication that affects the eyes, have been identified by a multi-department research team from Michigan State and other universities.

Their findings were recently published in Diabetologia, the official journal of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Additional contributors are from the University of Alabama at Birmingham, Case Western Reserve University and Western University ...

New model helps FAMU-FSU researchers locate best spots for field hospitals after disasters

2023-09-05

FAMU-FSU College of Engineering researchers want Floridians to be prepared when the next pandemic or hurricane hits the state. A new study published in the International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction examines the best locations for field hospitals that can supplement health care facilities when resources are stretched thin.

“One of the goals of RIDER is to look after our most vulnerable when disasters hit,” said Eren Ozguven, director of the Resilient Infrastructure ...

OHSU scientists discover new cause of Alzheimer’s, vascular dementia

2023-09-05

Researchers have discovered a new avenue of cell death in Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia.

A new study, led by scientists at Oregon Health & Science University and published online in the journal Annals of Neurology on Aug. 21, reveals for the first time that a form of cell death known as ferroptosis — caused by a buildup of iron in cells — destroys microglia cells, a type of cell involved in the brain’s immune response, in cases of Alzheimer’s and vascular dementia.

The ...

JNM publishes consensus statement on patient selection and appropriate use of Lu-177 PSMA-617 radionuclide therapy

2023-09-05

Reston, VA—The Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging (SNMMI) has issued a new consensus statement to provide standardized guidance for the selection and management of metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC) patients being treated with 177Lu-PSMA radionuclide therapy. The statement, published in the July issue of The Journal of Nuclear Medicine, also reviews current clinical struggles physicians face during treatment with 177Lu-PSMA-617 radionuclide therapy.

Recently, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved 177Lu-PSMA-617 for the treatment of men with mCRPC after progressing on taxane-based chemotherapy ...

Making plant-based meat more ‘meaty’ — with fermented onions

2023-09-05

Plant-based alternatives such as tempeh and bean burgers provide protein-rich options for those who want to reduce their meat consumption. However, replicating meat's flavors and aromas has proven challenging, with companies often relying on synthetic additives. A recent study in ACS’ Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry unveils a potential solution: onions, chives and leeks that produce natural chemicals akin to the savory scents of meat when fermented with common fungi.

When food producers want to make plant-based meat alternatives taste ...

Water-quality risks linked more to social factors than money

2023-09-05

When we determine which communities are more likely to get their water from contaminated supplies, median household income is not the best measure.

That’s according to a recent study led by researchers at The University of Texas at Austin that found social factors — such as low population density, high housing vacancy, disability and race — can have a stronger influence than median household income on whether a community’s municipal water supply is more likely to have health-based water-quality violations. In general, rural communities and communities that grew up around large industries that have since left are most likely to face water-quality issues.

About 10% ...

Researchers use AI to find new magnetic materials without critical elements

2023-09-05

A team of scientists from Ames National Laboratory developed a new machine learning model for discovering critical-element-free permanent magnet materials. The model predicts the Curie temperature of new material combinations. It is an important first step in using artificial intelligence to predict new permanent magnet materials. This model adds to the team’s recently developed capability for discovering thermodynamically stable rare earth materials.

High performance magnets are essential for technologies such as wind energy, data storage, electric vehicles, ...

Aging alters pancreatic circadian rhythm

2023-09-05

“Overall, our study identified previously unknown circadian transcriptome reorganization of pancreas by aging [...]”

BUFFALO, NY- September 5, 2023 – A new research paper was published in Aging (listed by MEDLINE/PubMed as "Aging (Albany NY)" and "Aging-US" by Web of Science) Volume 15, Issue 16, entitled, “Reorganization of pancreas circadian transcriptome with aging.”

The evolutionarily conserved circadian system allows organisms to synchronize internal processes with 24-h cycling environmental timing cues, ensuring optimal adaptation. Like other organs, the pancreas function is under circadian control. Recent evidence ...

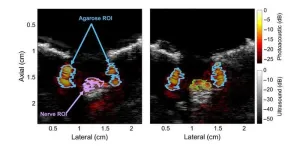

Visualizing nerves with photoacoustic imaging

2023-09-05

Invasive medical procedures, such as surgery requiring local anesthesia, often involve the risk of nerve injury. During operation, surgeons may accidentally cut, stretch, or compress nerves, especially when mistaking them for some other tissue. This can lead to long-lasting symptoms in the patient, including sensory and motor problems. Similarly, patients receiving nerve blockades or other types of anesthesia can suffer from nerve damage if the needle is not placed at the correct distance from the targeted peripheral nerve.

Consequently, researchers have been trying to develop medical imaging techniques to mitigate the risk of nerve damage. For instance, ultrasound and magnetic resonance ...

Study of “revolving door” in Washington shows one-third of HHS appointees leave for industry jobs

2023-09-05

LOS ANGELES – Almost one-third of government appointees to the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) leave to take jobs in private industry, according to a study by the USC Schaeffer Center for Health Policy & Economics and Harvard University.

The study, published in Health Affairs, is the first to quantify the personnel movement between health-care industries and the government agencies that regulate them, according to the authors. Although there are understandable reasons for people to move between the public and private sectors, the study notes that such a revolving door could make government agencies more vulnerable to pro-industry bias.

“Laws passed ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Breaking through water treatment limits with defect-free, high-efficiency next-generation ceramic filters!

Researchers determine structural motifs of water undecamer cluster

Researchers enhance photocatalytic hydrogen evolution performance of covalent organic frameworks by constitutional isomer strategy

Molecular target drives immunogenicity in cancer immunotherapy

Plant cell structure could hold key to cancer therapies and improved crops

Sustainable hydrogen peroxide production: Breakthroughs in electrocatalyst design for on-site synthesis

Cash rewards for behavior change: A review of financial incentives science in one health contexts and implications

One Health antimicrobial resistance modelling: from science to policy

Artificial feeding platform transforms study of ticks and their diseases

Researchers uncover microscopic mechanism of alkali species dissolution in water clusters

Methionine restriction for cancer therapy: A comprehensive review of mechanisms and clinical applications

White House autism briefing linked to swift shifts in prescribing patterns, study finds

Specialist palliative care can save the NHS up to £8,000 per person and improves quality of life

New research warns charities against ‘AI shortcut’ to empathy

Cannabis compounds show promise in fighting fatty liver disease

Study in mice reveals the brain circuits behind why we help others

Online forum to explore how organic carbon amendments can improve soil health while storing carbon

Turning agricultural plastic waste into valuable chemicals with biochar catalysts

Hidden viral networks in soil microplastics may shape the future of sustainable agriculture

Americans don’t just fear driverless cars will crash — they fear mass job losses

Mayo Clinic researchers find combination therapy reduces effects of ‘zombie cells’ in diabetic kidney disease

Preventing breast cancer resistance to CDK4/6 inhibitors using genomic findings

Carbon nanotube fiber ‘textile’ heaters could help industry electrify high-temperature gas heating

Improving your biological age gap is associated with better brain health

Learning makes brain cells work together, not apart

Engineers improve infrared devices using century-old materials

Physicists mathematically create the first ‘ideal glass’

Microbe exposure may not protect against developing allergic disease

Forest damage in Europe to rise by around 20% by 2100 even if warming is limited to 2°C

Rapid population growth helped koala’s recovery from severe genetic bottleneck

[Press-News.org] Fossil spines reveal deep sea’s pastResearch team led by Göttingen University describe early occurrence of irregular sea urchins in the depths of the oceans