(Press-News.org) CORVALLIS, Ore. – Oregon State University research has uncovered a possible clue as to why glaciers that terminate at the sea are retreating at unprecedented rates: the bursting of tiny, pressurized bubbles in underwater ice.

Published today in Nature Geoscience, the study shows that glacier ice, characterized by pockets of pressurized air, melts much more quickly than the bubble-free sea ice or manufactured ice typically used to research melt rates at the ocean-ice interface of tidewater glaciers.

Tidewater glaciers are rapidly retreating, the authors say, resulting in ice mass loss in Greenland, the Antarctic Peninsula and other glacierized regions around the globe.

“We have known for a while that glacier ice is full of bubbles,” said Meagan Wengrove, assistant professor of coastal engineering in the OSU College of Engineering and the leader of the study. “It was only when we started talking about the physics of the process that we realized those bubbles may be doing a lot more than just making noise underwater as the ice melts.”

Glacier ice results from the compaction of snow. Air pockets between snowflakes are trapped in pores between ice crystals as the ice makes its way from the upper layer of a glacier to deep inside it. There are about 200 bubbles per cubic centimeter, meaning glacier ice is about 10% air.

“These are the same bubbles that preserve ancient air studied in ice cores,” said co-author Erin Pettit, glaciologist and professor in the OSU College of Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Sciences. “The tiny bubbles can have very high pressures – sometimes up to 20 atmospheres, or 20 times normal atmospheric pressure at sea level.”

When the bubbly ice reaches the interface with the ocean, the bubbles burst and create audible pops, she added.

“The existence of pressurized bubbles in glacier ice has been known for a long time but no studies had looked at their effect on melting where a glacier meets the ocean, even though bubbles are known to affect fluid mixing in multiple processes ranging from industrial to medical,” Wengrove said.

Lab-scale experiments performed in this study suggest bubbles may explain part of the difference between observed and predicted melt rates of tidewater glaciers, she said.

“The explosive bursts of those bubbles, and their buoyancy, energize the ocean boundary layer during melting,” Wengrove said.

That carries huge implications for the way ice melt is folded into climate models, especially those that deal with the upper 40 to 60 meters of the ocean – the researchers learned glacier ice melts more than twice as fast as ice with no bubbles.

“While we can measure the amount of overall ice loss from Greenland over the last decade and we can see the retreat of each glacier in satellite images, we rely on models to predict ice melt rates,” Pettit said. “The models currently used to predict ice melt at the ice-ocean interface of tidewater glaciers do not account for bubbles in glacier ice.”

Right now, data from NASA attributes about 60% of sea level rise to meltwater from glaciers and ice sheets, the authors note. More accurate characterization of how ice melts will lead to better predictions of how quickly glaciers retreat, which is important because “it’s a lot more difficult for a community to plan for a 10-foot increase in water level than it is for a 1-foot increase,” Wengrove said.

“Those little bubbles may play an outsized role in understanding critical future climate scenarios,” she added.

The Keck Foundation, the National Science Foundation and the National Geographic Society funded the research, which also included Jonathan Nash and Eric Skyllingstad of the OSU College of Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Sciences and Rebecca Jackson of Rutgers University.

END

Bursting air bubbles may play a key role in how glacier ice melts, Oregon State research suggests

2023-09-07

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

A secret passage for mutant protein to invade the brain

2023-09-07

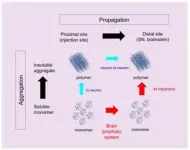

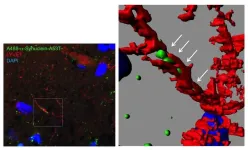

Researchers from Tokyo Medical and Dental University (TMDU) show that the protein involved in Parkinson’s disease, α-synuclein, can propagate through the lymphatic system of the brain before it aggregates

Tokyo, Japan – In many neurodegenerative disorders, abnormal proteins progressively aggregate and propagate in the brain. But what comes first, aggregation or propagation? Researchers from Japan share some new insights about the mechanism involved in Parkinson’s disease.

In a study published ...

The need to hunt small prey compelled prehistoric humans to produce appropriate hunting weapons and improve their cognitive abilities

2023-09-07

A new study from the Department of Archaeology at Tel Aviv University found that the extinction of large prey, upon which human nutrition had been based, compelled prehistoric humans to develop improved weapons for hunting small prey, thereby driving evolutionary adaptations. The study reviews the evolution of hunting weapons from wooden-tipped and stone-tipped spears, all the way to the sophisticated bow and arrow of a later era, correlating it with changes in prey size and human culture and physiology.

The researchers explain: "This study was designed to examine a broader unifying hypothesis, which we proposed in a previous paper published in ...

Bioprinting methods for fabricating in vitro tubular blood vessel models

2023-09-07

A review paper by scientists at the Chonnam National University summarized the recent research on bioprinting methods for fabricating bioengineered blood vessel models. The new review paper, published on Aug. 1 in the journal Cyborg and Bionic Systems, provided an overview on the 3D bioprinting methods for fabricating bioengineered blood vessel models and described possible advancements from tubular to vascular models.

“3D bioprinting technology provides a more precise and effective means for investigating biological processes and developing new treatments than traditional 2D cell cultures. Therefore, it is a crucial tool ...

Titanium culture vessel presenting temperature gradation for the thermotolerance estimation of cells

2023-09-07

Hyperthermia is a potentially non-invasive cancer treatment that capitalizes on the heat intolerance of cancer cells, which are more sensitive than normal cells. In order to induce effective hyperthermia, it is necessary to apply the appropriate temperature according to the cell type, i.e., to comprehensively study the thermal toxicity of the cells, which requires accurate regulation of the culture temperature. Researchers from Keio University in Japan have developed a cell culture system with temperature ...

1 in 2 patients had better blood pressure control after using remote, bilingual program

2023-09-07

Research Highlights:

More than half of adults (55%) with uncontrolled blood pressure who enrolled in a digital monitoring program that connected patients with clinical advice and included a bilingual app paired with at-home blood pressure monitors had controlled final blood pressure measurements after participating for least 90 days.

Patients using the Spanish-language version of the digital monitoring program demonstrated more improvement in blood pressure control than patients who used the English-language version.

Embargoed until 6:30a.m. CT/7:30 a.m. ET Thursday, Sept. 7, 2023

BOSTON, Sept. 7, 2023 — Over half of patients ...

High blood pressure while lying down linked to higher risk of heart health complications

2023-09-07

Research Highlights:

An analysis of data from a long-running study of more than 11,000 adults from four diverse communities in the United States has found that adults who had high blood pressure while both seated upright and lying supine (flat on their backs) had a higher risk of heart disease, stroke, heart failure or premature death compared to adults without high blood pressure while upright and supine.

Adults who had high blood pressure while lying supine but not while seated upright had similar elevated risks of heart attack, stroke, ...

Cold weather may pose challenges to treating high blood pressure

2023-09-07

Research Highlights:

An analysis of electronic health records for more than 60,000 adults in the United States found that systolic, or top-number, blood pressure rose slightly during the winter compared to summer months. The health records were of adults being treated for high blood pressure from 2018 to 2023 at six health care centers of varying sizes located in the southeast and midwestern United States.

The researchers found that, on average, participants’ systolic blood pressure increased by up to 1.7 mm Hg in the winter months compared to the summer months.

They also found that population ...

Community-based, self-measured blood pressure control programs helped at-risk patients

2023-09-07

Research Highlights:

Community health centers participating in the National Hypertension Control Initiative (NHCI) that introduced self-measured blood pressure interventions to their patients — including individuals from Black, Hispanic and American Indian/Alaskan Native populations, who are disproportionately impacted by hypertension and by the COVID-19 pandemic — experienced improvements in blood pressure control rates since 2021, when NHCI began.

Community Health Centers in the NHCI that received funding from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Service’s Health Resources and Services Administration and Office of Minority Health and ...

Amsterdam UMC study finds elite athletes safely return to top-level sports after COVID-19: no issues found in more than 2 years of follow-up

2023-09-07

Heart problems after a COVID infection are a serious concern for both elite athletes and recreational athletes alike. A study from Amsterdam UMC, published today in Heart, offers some reassuring news. "We examined over 250 elite athletes and found that those who had contracted COVID-19 did not experience severe heart issues that impacted their careers," says Juliette van Hattum, a PhD candidate in sports cardiology at Amsterdam UMC.

The study specifically focused on elite athletes, a group that could be particularly susceptible to heart issues, particularly heart ...

Stability inspection for West Antarctica shows: marine ice sheet is not destabilized yet, but possibly on a path to tipping

2023-09-07

Antarctica’s vast ice masses seem far away, yet they store enough water to raise global sea levels by several meters. A team of experts from European research institutes has now provided the first systematic stability inspection of the ice sheet’s current state. Their diagnosis: While they found no indication of irreversible, self-reinforcing retreat of the ice sheet in West Antarctica yet, global warming to date could already be enough to trigger the slow but certain loss of ice over the next hundreds to thousands ...