EVANSTON, Ill. — Northwestern University researchers have developed the first electronic device for continuously monitoring the health of transplanted organs in real time.

Sitting directly on a transplanted kidney, the ultrathin, soft implant can detect temperature irregularities associated with inflammation and other body responses that arise with transplant rejection. Then, it alerts the patient or physician by wirelessly streaming data to a nearby smartphone or tablet.

In a new study, the researchers tested the device on a small animal model with transplanted kidneys and found the device detected warning signs of rejection up to three weeks earlier than current monitoring methods. This extra time could enable physicians to intervene sooner, improving patient outcomes and wellbeing as well as increasing the odds of preserving donated organs, which are increasingly precious due to rising demand amid an organ-shortage crisis.

The study will publish Friday (Sept. 8) in the journal Science.

Rejection can occur at any time after a transplant — immediately after the transplant or years down the road. It is often silent, and patients might not experience symptoms, the study authors said.

“I have noticed many of my patients feel constant anxiety — not knowing if their body is rejecting their transplanted organ or not,” said Dr. Lorenzo Gallon, a Northwestern Medicine transplant nephrologist, who led the clinical portion of the study. “They may have waited years for a transplant and then finally received one from a loved one or deceased donor. Then, they spend the rest of their lives worrying about the health of that organ. Our new device could offer some protection, and continuous monitoring could provide reassurance and peace of mind.”

Northwestern’s John A. Rogers, a bioelectronics pioneer who led the device development, said it’s critical to identify rejection events as soon as they occur.

“If rejection is detected early, physicians can deliver anti-rejection therapies to improve the patient’s health and prevent them from losing the donated organ,” Rogers said. “In worst-case scenarios, if rejection is ignored, it could be life threatening. The earlier you can catch rejection and engage therapies, the better. We developed this device with that in mind.”

“Each individual responds to anti-rejection therapy differently,” said Surabhi Madhvapathy, a postdoctoral researcher in Rogers’ laboratory and the paper’s first author. “Real-time monitoring of the health of the patient’s transplanted organ is a critical step toward personalized dosing and medicine.”

Gallon also is a professor of nephrology and hypertension and organ transplantation at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. Rogers is the Louis Simpson and Kimberly Querrey Professor of Materials Science and Engineering, Biomedical Engineering and Neurological Surgery at Northwestern’s McCormick School of Engineering and director of the Querrey Simpson Institute for Bioelectronics (QSIB). Gallon and Rogers co-led the study with Dr. Jenny Zhang, a research professor of organ transplantation at Feinberg.

Current monitoring challenges

For the more than 250,000 people in the U.S. living with a transplanted kidney, monitoring their organ’s health is an ongoing journey. The easiest way to monitor kidney health is through measuring certain markers in the blood. By tracking the patient’s creatinine and blood urea nitrogen levels, physicians can gain insight into kidney function. But creatinine and blood urea nitrogen levels can fluctuate for reasons unrelated to organ rejection, so tracking these biomarkers is neither sensitive nor specific, sometimes leading to false negatives or positives.

The current “gold standard” for detecting rejection is a biopsy, in which a physician uses a long needle to extract a tissue sample from the transplanted organ and then analyzes the sample for signs of impending rejection. But invasive procedures like biopsies carry risks of multiple complications, including bleeding, infection, pain and even inadvertent damage to nearby tissues.

“The turnaround time can be quite long, and they are limited in monitoring frequencies and require off-site analysis,” Gallon said. “It might take four or five days to get results back. And those four or five days could be crucial in making a timely decision for the care of the patient.”

Timing and temperature

Northwestern’s new bioelectronic implant, by contrast, monitors something much simpler and more reliable: temperature. Because temperature increases typically accompany inflammation, the researchers hypothesized that sensing anomalous temperature increases and unusual variations in temperature might provide an early warning sign for potential transplant rejection.

The animal study confirmed just that. In the study, the researchers noticed that the local temperature of a transplanted kidney increases — sometimes as much as 0.6 degrees Celsius — preceding rejection events.

In animals without immunosuppressant medications, temperatures increased two or three days before biomarkers changed in blood samples. In animals taking immunosuppressant medications, the temperature not only increased but also displayed additional variations as much as three weeks before creatinine and blood urea nitrogen increased.

“Organ temperature fluctuates over a daily cycle under normal circumstances,” Madhvapathy said. “We observed abnormal higher frequency temperature variations occurring over periods of 8 and 12 hours in cases of transplant rejection.”

Said Gallon: “Histological damage occurs even when creatinine is normal. Even though kidney function appears normal, the signs of rejection in the blood might be lagging a few days behind.”

Not only does the new device detect rejection signs earlier than other methods, it also offers continuous, real-time monitoring. Right after transplant surgeries, patients might get blood tests more than once per week. But, over time, blood tests become less frequent, leaving patients in the dark for weeks at a time.

Patient ‘walks a tightrope’

Dr. Joaquin Brieva, a Northwestern Medicine dermatologist, is familiar with waiting and wondering. Born with a congenital form of kidney disease, Brieva received a kidney transplant in September 2022.

“Within two days of my transplant, my kidney function was back to normal,” said Brieva, who was not involved with the study. “But then you worry about the possibility of kidney rejection. That’s why you have these potent anti-rejection drugs and steroids. You’re walking a tightrope of anxiety about infections, complications from the drugs, various side effects and rejection of the kidney. You can manage some of that concern with medication adjustments, but kidney rejection remains prevalent. Your transplanted kidney is extremely precious, so that was my biggest concern.”

“It’s not like we can just triple or quadruple anti-rejection medications to avoid a rejection because these medications carry their own risks,” Gallon said. “Immunosuppressants can lower the entire immune system and are associated with infections and even cancer. We don’t want to increase dosages unless there is a sign that we absolutely need to.”

For Brieva, who has lost nine family members to renal failure, and for other organ recipients, a device that continuously monitors organ health could help avoid unnecessary medications while providing much-needed peace of mind.

“Having this device would be reassuring,” he said. “It can pick up any sudden changes in the kidney transplant and detect acute rejection, which currently gives no warning signs.”

About the device

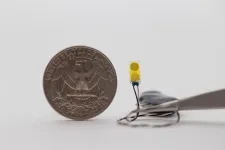

The sensor itself is tiny. At just 0.3 centimeters wide, 0.7 centimeters long and 220 microns thick, it is smaller than a pinky fingernail and about the width of a single hair. To affix it to the kidney, Rogers and his team took advantage of the organ’s natural biology. The entire kidney is encapsulated by a fibrous layer, called the renal capsule, that protects the organ from damage. Rogers’ team designed the sensor to fit just beneath the capsule layer, where it rests snugly against the kidney.

“The capsule keeps the device in good thermal contact with the underlying kidney,” Rogers said. “Bodies move, so there is a lot of motion to deal with. Even the kidney itself moves. And it’s soft tissue without good anchor points for sutures. These were daunting engineering challenges, but this device is a gentle, seamless interface that avoids risking damage to the organ.”

The device contains a highly sensitive thermometer, which can detect incredibly slight (0.004 degrees Celsius) temperature variations on the kidney — and only the kidney. (The sensor also measures blood flow, although the researchers found temperature was a better indicator of rejection.)

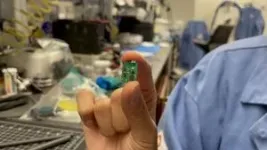

The sensors are then connected to a tiny package of electronics — including a miniature coin cell battery for power — which sit next to the kidney and use Bluetooth technology to stream data continuously and wirelessly to external devices.

“All electronic components are encased in a soft, biocompatible plastic that is gentle and flexible against the kidney’s delicate tissues,” Madhvapathy said. “The surgical insertion of the entire system, which is smaller than a quarter, is a quick and easy procedure.”

“We imagine that a surgeon could implant the device immediately following the transplant surgery, while the patient is still in the operating room,” Rogers said. “Then, it can monitor the kidney without requiring additional procedures.”

What’s next?

After the success of the small animal trial, the researchers are now testing the system in a larger animal model. Rogers and his team also are evaluating ways to recharge the coin cell battery so that it can last a lifetime.

While the primary studies were conducted with kidney transplants, the researchers assume it could also work for other organ transplants, including the liver and lungs and to other disease models.

The study, “Implantable bioelectronic systems for early detection of kidney transplant rejection,” was supported by the National Science Foundation and an Alpha Omega Alpha Carolyn L. Kuckein Student Research Fellowship.

END