(Press-News.org) The passenger pigeon. The Tasmanian tiger. The Baiji, or Yangtze river dolphin. These rank among the best-known recent victims of what many scientists have declared the sixth mass extinction, as human actions are wiping out vertebrate animal species hundreds of times faster than they would otherwise disappear.

Yet, a recent analysis from Stanford University and the National Autonomous University of Mexico, published this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, shows the crisis may run even deeper. Each of the three species above was also the last member of its genus, the higher category into which taxonomists sort species. And they aren’t alone.

Up to now, public and scientific interest has focused on extinctions of species. But in their new study, Gerardo Ceballos, senior researcher at the Institute of Ecology at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, and Paul Ehrlich, Bing Professor of Population Studies, Emeritus, in the Stanford School of Humanities and Sciences, have found that entire genera (the plural of “genus”) are vanishing as well, in what they call a “mutilation of the tree of life.”

“In the long term, we’re putting a big dent in the evolution of life on the planet,” Ceballos said. “But also, in this century, what we’re doing to the tree of life will cause a lot of suffering for humanity.”

“What we’re losing are our only known living companions in the entire universe,” said Ehrlich, who is also a senior fellow, emeritus, by courtesy, at the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment.

A ‘biological annihilation’

Information on species’ conservation statuses from the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, Birdlife International, and other databases has improved in recent years, which allowed Ceballos and Ehrlich to assess extinction at the genus level. Drawing from those sources, the duo examined 5,400 genera of land-dwelling vertebrate animals, encompassing 34,600 species.

Seventy-three genera of land-dwelling vertebrates, Ceballos and Ehrlich found, have gone extinct since 1500 AD. Birds suffered the heaviest losses with 44 genus extinctions, followed in order by mammals, amphibians, and reptiles.

Based on the historic genus extinction rate among mammals – estimated for the authors by Anthony Barnosky, professor emeritus of integrative biology at UC Berkeley – the current rate of vertebrate genus extinction exceeds that of the last million years by 35 times. This means that, without human influence, Earth would likely have lost only two genera during that time. In five centuries, human actions have triggered a surge of genus extinctions that would otherwise have taken 18,000 years to accumulate – what the paper calls a “biological annihilation.”

“As scientists, we have to be careful not to be alarmist,” Ceballos acknowledged – but the gravity of the findings in this case, he explained, called for more powerful language than usual. “We would be unethical not to explain the magnitude of the problem, since we and other scientists are alarmed.”

Next-level loss, next-level consequences

On many levels, genus extinctions hit harder than species extinctions.

When a species dies out, Ceballos explained, other species in its genus can often fill at least part of its role in the ecosystem. And because those species carry much of their extinct cousin’s genetic material, they also retain much of its evolutionary potential. Pictured in terms of the tree of life, if a single “twig” (a species) falls off, nearby twigs can branch out relatively quickly, filling the gap much as the original twig would have. In this case, the diversity of species on the planet remains more or less stable.

But when entire “branches” (genera) fall off, it leaves a huge hole in the canopy – a loss of biodiversity that can take tens of millions of years to “regrow” through the evolutionary process of speciation. Humanity cannot wait that long for its life-support systems to recover, Ceballos said, given how much the stability of our civilization hinges on the services Earth’s biodiversity provides.

Take the increasing prevalence of Lyme disease: white-footed mice, the primary carriers of the disease, used to compete with passenger pigeons for foods, like acorns. With the pigeons gone and predators like wolves and cougars on the decline, mouse populations have boomed – and with them, human cases of Lyme disease.

This example involves the disappearance of just one genus. A mass extinction of genera could mean a proportional explosion of disasters for humanity.

It also means a loss of knowledge. Ceballos and Ehrlich point to the gastric brooding frog, also the final member of an extinct genus. Females would swallow their own fertilized eggs and raise tadpoles in their stomachs, while “turning off” their stomach acid. These frogs might have provided a model for studying human diseases like acid reflux, which can raise the risk of esophageal cancer – but now they’re gone.

Loss of genera could also exacerbate the worsening climate crisis. “Climate disruption is accelerating extinction, and extinction is interacting with the climate, because the nature of the plants, animals, and microbes on the planet is one of the big determinants of what kind of climate we have,” Ehrlich pointed out.

A crucial, and still absent, response

To prevent further extinctions and resulting societal crises, Ceballos and Ehrlich are calling for immediate political, economic, and social action on unprecedented scales.

Increased conservation efforts should prioritize the tropics, they noted, since tropical regions have the highest concentration of both genus extinctions and genera with only one remaining species. The pair also called for increased public awareness of the extinction crisis, especially given how deeply it intersects with the more-publicized climate crisis.

“The size and growth of the human population, the increasing scale of its consumption, and the fact that the consumption is very inequitable are all major parts of the problem,” the authors said.

“The idea that you can continue those things and save biodiversity is insane,” Ehrlich added. “It’s like sitting on a limb and sawing it off at the same time.”

Paul Ehrlich is also president of the Center for Conservation Biology at Stanford.

END

Study finds human-driven mass extinction is eliminating entire branches of the tree of life

2023-09-18

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

An implantable device could enable injection-free control of diabetes

2023-09-18

CAMBRIDGE, MA -- One promising approach to treating Type 1 diabetes is implanting pancreatic islet cells that can produce insulin when needed, which can free patients from giving themselves frequent insulin injections. However, one major obstacle to this approach is that once the cells are implanted, they eventually run out of oxygen and stop producing insulin.

To overcome that hurdle, MIT engineers have designed a new implantable device that not only carries hundreds of thousands of insulin-producing islet cells, but also has its own on-board oxygen factory, which generates oxygen by splitting water vapor found in the body.

The researchers showed that when ...

Buried ancient Roman glass formed substance with modern applications

2023-09-18

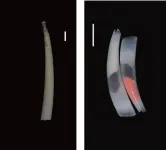

Some 2,000 years ago in ancient Rome, glass vessels carrying wine or water, or perhaps an exotic perfumes, tumble from a table in a marketplace, and shatter to pieces on the street. As centuries passed, the fragments were covered by layers of dust and soil and exposed to a continuous cycle of changes in temperature, moisture, and surrounding minerals.

Now these tiny pieces of glass are being uncovered from construction sites and archaeological digs and reveal themselves to be something extraordinary. On their surface is a mosaic of iridescent colors of blue, green and orange, with some displaying shimmering gold-colored ...

Genomes of enigmatic tusk shells provide new insights into early Molluscan evolution

2023-09-18

Accurate phylogenetic trees are fundamental to evolutionary and comparative biology, but the almost simultaneous emergence of major animal phyla and diverse body plans during the Cambrian Explosion poses major challenges to reconstructing deep metazoan phylogenetic relationships.

This is particularly true for the second largest phylum, Mollusca, whose major lineages originated in the Cambrian period. The diverse fossil record, extreme morphological disparity among the eight living classes, and dramatic conflict among phylogenetic hypotheses due to diverse paleontological, ...

Remote work can slash your carbon footprint — if done right

2023-09-18

ITHACA, N.Y. – Remote workers can have a 54% lower carbon footprint compared with onsite workers, according to a new study by Cornell University and Microsoft, with lifestyle choices and work arrangements playing an essential role in determining the environmental benefits of remote and hybrid work.

The study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, also finds that hybrid workers who work from home two to four days per week can reduce their carbon footprint by 11% to 29%, but working from home one day per week ...

Preschoolers from low-income families may have worse health and benefit less from health promotion interventions than children with higher socioeconomic status

2023-09-18

Low socioeconomic status can negatively impact children’s health in preschool, along with their ability to follow specialized health education intervention programs, Mount Sinai researchers found in an international study focused on health promotion in schools, including those in the Harlem section of New York City. The results, published September 18 in the Journal of American College of Cardiology, stress the importance of introducing a specialized health curriculum in classrooms starting in preschool.

“This study shows that socioeconomic factors, including lower household income and education level, can negatively impact children’s health starting ...

Oregon State receives $7.5 million grant to build state of the art zebrafish biomedical research facility

2023-09-18

CORVALLIS, Ore. – Oregon State University has received a $7.5 million National Institutes of Health grant to modernize a lab focused on using zebrafish to address pressing human health challenges.

The Sinnhuber Aquatic Research Laboratory, led by Distinguished Professor Robyn Tanguay, a molecular toxicologist in the College of Agricultural Sciences, exploits the unique advantages of zebrafish to protect and improve human and environmental health. Zebrafish and humans have similar developmental processes and are similar on a genomic level, ...

Employee surveys may miss out on uncovering toxic leadership practices

2023-09-18

BINGHAMTON, N.Y. -- Standardized and overly simplistic questionnaires are only scratching the surface of what employees think of their leaders, according to new research from Binghamton University’s School of Management (SOM), and negative behavior may be slipping through the cracks.

As a result, the research finds, organizations may be missing out on critical information that could be keeping toxic leaders in positions of power.

“Instead of capturing actual leader behaviors, ratings might simply reflect whether a person likes their leader,” said Mengying ...

Key to solving Libyan conflict lies within the country, analysis says

2023-09-18

The key to solving the Libyan political conflict lies within the country rather than with the international community, analysis says.

Electoral and governance deadlock has been blamed for the devastating impact of the flooding in the country.

The “contentment” of the political elite and others with the status quo - given the currently limited levels of violence and the rising global prices of energy since the outbreak of Russia’s war on Ukraine - explains the general lack of a genuine commitment to relaunch the transition and electoral roadmap, ...

Personalized combination treatment turns on an immunometabolic switch to effectively control an aggressive form of prostate cancer

2023-09-18

Researchers at the University of Chicago Medicine Comprehensive Cancer Center established “proof-of-concept” for a new treatment approach that was able to effectively treat the most aggressive forms of prostate cancer. The treatment showed complete tumor control and long-lasting survival without side effects in a mouse model of advanced prostate cancer.

These findings, which were published online September 18, 2023, in Clinical Cancer Research, warrant further investigation in human clinical trials, the researchers concluded.

Strategies to overcome resistance

“Prostate cancer in the metastatic ...

Power meals: Child care-provided meals are associated with improved child and family health

2023-09-18

Philadelphia, September 18, 2023 – Very young children who attend child care and receive onsite meals and snacks were more likely to be food secure and in good health, and less likely to be admitted after a hospital emergency department visit than children in child care whose meals and snacks were provided from home, according to a new study in the Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, published by Elsevier. These potential benefits could extend beyond the children themselves to their families, including through possible reductions in stress, and to society as a whole through potentially significant healthcare cost savings.

Lead author Stephanie ...