(Press-News.org) Enforcement is one of the biggest challenges to international cooperation on mitigating climate change in the Paris Agreement. The agreement has no formal enforcement mechanism; instead, it is designed to be transparent so countries that fail to meet their obligations will be named and thus shamed into changing behavior. A new study from the University of California San Diego's School of Global Policy and Strategy shows that this naming-and-shaming mechanism can be an effective incentive for many countries to uphold their pledges to reduce emissions.

The study, appearing in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), assesses the naming and shaming built into the 2015 Paris Agreement through its Enhanced Transparency Framework (ETF). The ETF requires nations to publicly report their goals and progress toward meeting those goals. The study suggests that the ETF is most effective at motivating countries with the strongest commitments to slowing climate change.

“The architects of the Paris Agreement knew that powerful enforcement mechanisms, like trade sanctions, wouldn’t be feasible,” said study coauthor David Victor, professor of industrial innovation at UC San Diego’s School of Global Policy and Strategy and co-director of the Deep Decarbonization Initiative. “Most analysts assumed the agreement would fail to be effective without strong enforcement and are skeptical of naming and shaming. Our research suggests that pessimism is wrong. Naming and shaming is built into the system and our study shows that the policy experts who are most knowledgeable about Paris see this mechanism working well—at least for some countries.”

Naming and shaming doesn’t work everywhere, the study shows; however, it is particularly important for countries that are already highly motivated to act. Even those countries need a spotlight on their behavior, lest they slip and fail to comply with the obligations they set for themselves under the Paris Agreement.

In Europe—where countries have the most ambitious and credible climate pledges—the surge in energy prices and interruptions in Russian gas supply created incentives to retain higher-emission energy technologies, such as coal. International visibility and political pressures within those countries plausibly help explain why European policymakers have kept emissions in alignment with their previously committed climate goals.

In the U.S., naming and shaming is likely to be effective as well, but not to the same degree as in Europe, the study shows.

“This raises some concern about the ability to maintain the momentum generated by the Inflation Reduction Act under less favorable conditions, such as rising interest rates,” said Emily Carlton, study coauthor and UC San Diego School of Global Policy and Strategy alum.

Study taps expert opinions of top climate negotiators from around the world

The findings in the new PNAS study are derived from responses from a sample of registrants of the Conference of Parties (COP), consisting of more than 800 diplomatic and scientific experts who, for decades, have participated in climate policy debates. This expert group is critical to understanding how political institutions shape climate policy because they are the people “in the room” when key policy decisions are made. They are in a unique position to evaluate what is most likely to motivate their countries to act on climate.

They were asked questions such as: is the ETF in the agreement effective? Do they support the use of the ETF, and is it a legitimate way to enforce the Paris Agreement?

Overall, 77% of the sample agreed with using naming and shaming—that is, using the ETF for comparing countries’ mitigation efforts. The results further indicate that 57% of all respondents expect naming and shaming to substantially affect the climate policy performance of their home country—where they know the policy environment best.

While survey respondents’ country of origin was kept anonymous to elicit the most candid responses possible, the respondents that think naming and shaming is most effective are more likely to be from democracies with high-quality political institutions. In addition, these individuals come from countries with strong internal concern about climate change and ambitious and credible international climate commitments, such as countries in Europe.

The study finds naming and shaming is likely least effective for countries that lack strong democratic institutions, such as some large emitters like China.

While the inability for naming and shaming to work effectively within the countries least motivated for climate action creates tension, the study does provide a hopeful narrative for enforcing cooperation on climate, according to the authors.

“It is a really good thing that naming and shaming can keep the most climate-motivated countries on track because decarbonizing is hard and changes in circumstances and energy markets can make it even harder,” said Carlton. “Countries in Europe are some of the biggest emitters and as we saw recently, policymakers could have easily switched back to coal after the Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, but they did not.”

Who should be the “namers and shamers” and who is most effective at it?

The survey respondents were also asked which institutions should be responsible for naming and shaming. The results overwhelmingly indicated the preference for namers and shamers to be scientists, as well as neutral international organizations such as the United Nations (U.N.) and Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). However, past studies have found that both diplomatic and science organizations like the U.N. and IPCC are actually ineffective at naming and shaming.

“It is not something that these organizations do,” Carlton said. “They are positioned to try to get countries to cooperate and it’s just not a function of theirs to put countries on blast in a judgmental way. That is something you see done more effectively from non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and the media.”

While naming and shaming is a mechanism that makes cooperation work, the authors believe that other strategies such as trade sanctions may be useful as well. They explore this topic in a forthcoming study.

Coauthors of the PNAS paper, “Naming and Shaming as a Strategy for Enforcing the Paris Agreement: The Role of Political Institutions and Public Concern,” include Astrid Dannenberg of University of Kassel and the University of Gothenburg and Marcel Lumkowsky of the University of Kassel.

END

Naming and shaming can be effective to get countries to act on climate

New UC San Diego study finds the transparency rules in the Paris Agreement could keep many countries on track to meet goals stated in the international treaty

2023-09-25

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

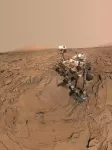

Scientists develop method of identifying life on other worlds

2023-09-25

Humankind is looking for life on other planets, but how will we recognise it when we see it? Now a group of US scientists have developed an artificial-intelligence-based system which gives 90% accuracy in discovering signs of life.

The work was presented to scientists for the first time at the Goldschmidt Geochemistry Conference in Lyon on Friday 14th July, where it received a positive reception from others working in the field. The details have now been published in the peer-reviewed journal PNAS (see notes for details).

Lead researcher Professor Robert Hazen, of the Carnegie Institution’s Geophysical ...

Caribbean parrots thought to be endemic are actually relicts of millennial-scale extinction

2023-09-25

In a new study published in PNAS, researchers have extracted the first ancient DNA from Caribbean parrots, which they compared with genetic sequences from modern birds. Working with fossils and archaeological specimens, they showed that two species thought to be endemic to particular islands were once more widespread and diverse. The results help explain how parrots rapidly became the world’s most endangered group of birds, with 28% of all species considered to be threatened. This is especially true for parrots that inhabit islands.

On ...

CSIC contributes to deciphering the enigmatic global distribution of fairy circles

2023-09-25

One of the most impressive and mysterious natural formations that we can observe in the arid areas of our planet are the fairy circles. These are enigmatic circular patterns of bare soil surrounded by plants generating rings of vegetation, which until now had only been described in Namibia and Australia. Over the years, multiple hypotheses have been proposed to explain their formation, which have given rise to numerous discussions about the mechanisms that give rise to them. However, until now, we did not know the global dimension of this type of phenomena and the environmental ...

Insilico Medicine and University of Cambridge present new approach to discover targets for Alzheimer’s and other diseases with protein phase separation

2023-09-25

New York and Cambridge, UK -- Recent research demonstrates that protein phase separation (PPS) is widely present in cells and drives a variety of important biological functions. Protein phase separation at the wrong place or time could create clogs or aggregates of molecules linked to neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, and poorly formed cellular condensates could contribute to cancers and might help explain the aging process.

Given the emerging association between human disease and the PPS process, scientists have been looking for ways to identify potential targets for therapeutic interventions based on PPS regulation. Today, Insilico ...

Antibiotics can help some bacteria survive for longer

2023-09-25

Scientists have found a surprising effect of some antibiotics on certain bacteria – that the drugs can sometimes benefit bacteria, helping them live longer.

Until now, it has been widely acknowledged that antibiotics kill bacteria or stop them growing, making them widely used as blanket medication for bacterial infections. In recent years, the rise of antibiotic resistance has stopped some antibiotics from working, meaning that untreatable infections could be the biggest global cause of death by 2050.

Now, researchers at the University of Exeter have shown for the first time that antibiotics ...

New method can improve assessing genetic risks for non-white populations

2023-09-25

A team led by researchers at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and the National Cancer Institute has developed a new algorithm for genetic risk-scoring for major diseases across diverse ancestry populations that holds promise for reducing health care disparities.

Genetic risk-scoring algorithms are considered a promising method to identify high-risk groups of individuals who could benefit from preventive interventions for various diseases and conditions, such as cancers and heart diseases. ...

Wearable devices show who may need more help managing diabetes

2023-09-25

A new Dartmouth study in the journal Science Advances suggests that how well people with diabetes manage their blood sugar depends on their experience with the condition and their overall success in controlling their glucose levels, as well as on the season and time of day. The findings could help physicians identify those patients who could benefit from more guidance in regulating their blood sugar, particularly at certain times of year.

The researchers accessed data from wearable glucose monitors that showed how 137 people in the U.S. aged 2 to 76 living primarily with type 1, aka juvenile, diabetes managed their blood sugar on a daily basis. By analyzing more ...

Light and sound waves reveal negative pressure

2023-09-25

As a physical quantity pressure is encountered in various fields: atmospheric pressure in meteorology, blood pressure in medicine, or even in everyday life with pressure cookers and vacuum-sealed foods. Pressure is defined as a force per unit area acting perpendicular to a surface of a solid, liquid, or gas. Depending on the direction in which the force acts within a closed system, very high pressure can lead to explosive reactions in extrem cases, while very low pressure in a closed system can cause the implosion of the system itself. Overpressure ...

Predicting how climate change affects infrastructure without damaging the subject

2023-09-25

A digital twin may sound like something out of a science fiction film, but Pitt engineers are developing new technology to make them a reality in our campus and beyond.

Digital twins – a model that serves as a real-time computational counterpart – can be used to help simulate the effects of multiple types of conditions, such as weather, traffic, and even climate change. Still, life-cycle assessments (LCAs) of climate change’s effects on infrastructure are still a work-in-progress, leaving a need ...

New qubit circuit enables quantum operations with higher accuracy

2023-09-25

In the future, quantum computers may be able to solve problems that are far too complex for today’s most powerful supercomputers. To realize this promise, quantum versions of error correction codes must be able to account for computational errors faster than they occur.

However, today’s quantum computers are not yet robust enough to realize such error correction at commercially relevant scales.

On the way to overcoming this roadblock, MIT researchers demonstrated a novel superconducting qubit ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Afraid of chemistry at school? It’s not all the subject’s fault

How tech-dependency and pandemic isolation have created ‘anxious generation’

Nearly three quarters of US baby foods are ultra-processed, new study finds

Nonablative radiofrequency may improve sexual function in postmenopausal women

Pulsed dynamic water electrolysis: Mass transfer enhancement, microenvironment regulation, and hydrogen production optimization

Coordination thermodynamic control of magnetic domain configuration evolution toward low‑frequency electromagnetic attenuation

High‑density 1D ionic wire arrays for osmotic energy conversion

DAYU3D: A modern code for HTGR thermal-hydraulic design and accident analysis

Accelerating development of new energy system with “substance-energy network” as foundation

Recombinant lipidated receptor-binding domain for mucosal vaccine

Rising CO₂ and warming jointly limit phosphorus availability in rice soils

Shandong Agricultural University researchers redefine green revolution genes to boost wheat yield potential

Phylogenomics Insights: Worldwide phylogeny and integrative taxonomy of Clematis

Noise pollution is affecting birds' reproduction, stress levels and more. The good news is we can fix it.

Researchers identify cleaner ways to burn biomass using new environmental impact metric

Avian malaria widespread across Hawaiʻi bird communities, new UH study finds

New study improves accuracy in tracking ammonia pollution sources

Scientists turn agricultural waste into powerful material that removes excess nutrients from water

Tracking whether California’s criminal courts deliver racial justice

Aerobic exercise may be most effective for relieving depression/anxiety symptoms

School restrictive smartphone policies may save a small amount of money by reducing staff costs

UCLA report reveals a significant global palliative care gap among children

The psychology of self-driving cars: Why the technology doesn’t suit human brains

Scientists discover new DNA-binding proteins from extreme environments that could improve disease diagnosis

Rapid response launched to tackle new yellow rust strains threatening UK wheat

How many times will we fall passionately in love? New Kinsey Institute study offers first-ever answer

Bridging eye disease care with addiction services

Study finds declining perception of safety of COVID-19, flu, and MMR vaccines

The genetics of anxiety: Landmark study highlights risk and resilience

How UCLA scientists helped reimagine a forgotten battery design from Thomas Edison

[Press-News.org] Naming and shaming can be effective to get countries to act on climateNew UC San Diego study finds the transparency rules in the Paris Agreement could keep many countries on track to meet goals stated in the international treaty