(Press-News.org) Some substances in medicines, household items and the environment are known to affect prenatal child development. In a study published in Toxicological Sciences, researchers tested the effects of five drugs (including caffeine and the blood thinner warfarin) on the growth of zebrafish embryos. They found that all five had the same effect, impairing the migration of bone-forming cells which resulted in the onset of facial malformation. Zebrafish embryos grow quickly, are transparent and develop outside of the parent’s body, making them ideal for studying early development. A zebrafish-based system could be used to easily screen for potentially harmful substances, reducing animal testing on mammals and supporting parents-to-be when making choices for themselves and their baby.

Whether from birth or through events which happen in life, many people have differences in their facial appearance. Worldwide, over one-third of all congenital anomalies relate to the development of a child’s head or facial bones — their craniofacial features — a common example being having a cleft lip and/or palate. The exact cause of craniofacial differences is not fully understood, but researchers currently think that multiple factors may be involved. This includes genetics, the gestational parent’s environment, their diet, some illnesses and certain drugs or chemicals.

Teratogens are substances known to disturb the growth of an embryo or fetus; for example, pregnant people are advised to avoid alcohol and nicotine. Potential teratogens are typically screened for using animals such as rodents and rabbits. But researchers are looking for alternative methods which are quicker, cheaper and reduce the need for testing on mammals.

This is where zebrafish come in. These tiny, 2-5 centimeter freshwater fish grow very quickly, developing as much in a day as a human embryo would in a month. “Zebrafish embryos are transparent and grow outside the mother, so we can monitor the behavior of live cells as they develop,” said Toru Kawanishi, project assistant professor at the University of Tokyo’s Department of Biological Sciences at the time of the study. Within the past 10 years, several research projects have shown that zebrafish can effectively be used to check for teratogens. However, the exact mechanisms by which teratogens impair or alter typical embryonic development is still being investigated.

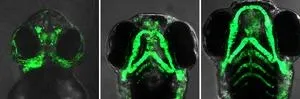

The team focused on a specific genetic marker for a group of cells involved in craniofacial development in both mammals and fish. In humans, these are known to become parts of the nose and jaw. “We manipulated the genome of zebrafish embryos and made bone-forming cells fluorescently visible in green. We then treated them with chemicals that are known to cause facial defects in human newborns, and tracked the trajectories of the bone-forming cells throughout embryonic stages,” explained Kawanishi.

The team tested five chemicals: valproic acid (used to treat neurological and psychiatric disorders), warfarin (an anticoagulant), salicylic acid (popular in skin ointments), caffeine and methotrexate (used in chemotherapy). They saw that, as expected, all the chemicals tested caused various degrees of craniofacial anomalies 96 hours after fertilization. However, they were surprised by the mechanism which caused this to happen and how quickly it started.

“Bone- and cartilage-forming cells in the head, called cranial neural crest cells (CNCCs), generally move a long distance from where they are first formed around the back of the neck, to their intended destinations such as the jaw or nose,” explained Kawanishi. “We were surprised that regardless of how each chemical acts on cells molecularly, impaired migration of bone-forming cells in early development was responsible for the onset of facial malformation for all the five chemicals. We could see signs of this within just 24 hours, at a point where zebrafish and mammalian embryos share very similar morphological and molecular characteristics.”

The results indicate the potential existence of a general mechanism by which teratogenic chemicals limit movement of CNCCs early on in embryos, causing the development of facial differences. The researchers extrapolate that facial differences caused by other substances might also follow the same mechanism. “We will aim to reveal the molecular mechanism underlying the impaired cell migration, to understand why different chemicals lead to the shared defects in cell migration,” said Kawanishi. The team proposes using this zebrafish-based system as another way to test for cross-species teratogens, so that parents and medical practitioners can be made aware to limit or avoid them.

###

Paper Title:

Shujie Liu, Toru Kawanishi, Atsuko Shimada, Naohiro Ikeda, Masayuki Yamane, Hiroyuki Takeda, Junichi Tasaki. “Identification of an adverse outcome pathway (AOP) for chemical-induced craniofacial anomalies using the transgenic zebrafish model” Toxicological Sciences, 2023, 1-14. DOI: 10.1093/toxsci/kfad078.

Declaration of competing interests

S.L., N.I., M.Y., and J.T. are employed by the company Kao. The author/authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Useful Links :

Graduate School of Science: https://www.s.u-tokyo.ac.jp/en/

Takeda Lab: https://www.bs.s.u-tokyo.ac.jp/~hassei/English/research%20E/research%20E.html

Research Contact:

Toru Kawanishi

Visiting researcher

Department of Biological Sciences,

Graduate School of Science

7-3-1 Hongo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 113-0033, Japan

Email: toru.kawanishi@bs.s.u-tokyo.ac.jp

Tel.: +81 45 924 5722

Press contact:

Mrs. Nicola Burghall

Public Relations Group, The University of Tokyo,

7-3-1 Hongo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 113-8654, Japan

press-releases.adm@gs.mail.u-tokyo.ac.jp

About the University of Tokyo

The University of Tokyo is Japan's leading university and one of the world's top research universities. The vast research output of some 6,000 researchers is published in the world's top journals across the arts and sciences. Our vibrant student body of around 15,000 undergraduate and 15,000 graduate students includes over 4,000 international students. Find out more at www.u-tokyo.ac.jp/en/ or follow us on Twitter at @UTokyo_News_en.

END

Sushi has become everyday fare in Norway and elsewhere around the globe, and many people opt for sashimi and other raw fish when they want to treat themselves to something tasty.

It is important to emphasise here that, as a general rule, it is completely safe to eat this type of food in Norway. However, despite the fact that sushi can be delicious, it also carries a health hazard, both for individuals and for society at large.

“Bacteria in sushi, sashimi and cold-smoked fish products can pose a risk to people who eat such foods frequently, especially people with weak immune systems, children and the elderly,” says Hyejeong Lee.

She recently completed her PhD at the Department ...

Researchers have found a link between a pregnant woman or her partner losing their job and an increased risk of miscarriage or stillbirth.

The study, which is published today (Thursday) in Human Reproduction [1], one of the world’s leading reproductive medicine journals, found a doubling in the chances of a pregnancy miscarrying or resulting in a stillbirth following a job loss.

The researchers, led by Dr Selin Köksal from the Institute for Social and Economic Research at the University of Essex, UK, ...

Researchers have established the protein p53 as critical for regulating sociability, repetitive behavior, and hippocampus-related learning and memory in mice, illuminating the relationship between the protein-coding gene TP53 and neurodevelopmental and psychiatric disorders like autism spectrum disorder.

“This study shows for the first time that p53 is linked directly to autism-like behavior,” said Nien-Pei Tsai, an associate professor of molecular and integrative biology at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and a researcher at the Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology.

In living systems, ...

Accessing stable employment with fair pay and predictable hours is harder for workers in the North and Midlands, which can severely affect their living standards, health, and future job prospects.

A new report published by the Work Foundation at Lancaster University reveals the regions with the highest and lowest levels of ‘severely insecure’ work (employment that is involuntarily temporary or part-time, or when multiple forms of insecurity come together, such as casual or zero-hours contracts, or low or unpredictable ...

Increased consumption of carbohydrate from refined grains, starchy vegetables, and sugary drinks is associated with greater weight gain throughout midlife, while increased fibre and carbohydrate from whole grains, fruit, and non-starchy vegetables is linked to less weight gain, finds a large US study published by The BMJ today.

Most of these associations were stronger for people with excessive body weight, highlighting the potential importance of carbohydrate quality and source for long term weight management, say the researchers.

The role of carbohydrates in weight gain and obesity remains controversial, and few studies have evaluated ...

Patients in some of the most deprived areas of England, where respiratory conditions including chronic lung disease (COPD) and asthma are most prevalent, have limited or no access to vital diagnostic tests to confirm their diagnosis, reveals a survey by The BMJ today.

Despite NHS England’s promise of access via Community Diagnostic Centres (CDCs), journalist Sally Howard speaks to GPs in some of the worst affected areas who say having no means of referring patients for lung function tests is “troubling” and “a silent scandal.”

And last month, a report by the charity Asthma + Lung UK ...

A project mapping medieval England’s known murder cases has now added Oxford and York to its street plan of London’s 14th century slayings, and found that Oxford’s student population was by far the most lethally violent of all social or professional groups in any of the three cities.

The team behind the Medieval Murder Maps – a digital resource that plots crime scenes based on translated investigations from 700-year-old coroners’ inquests – estimate the per capita homicide ...

Cambridge researchers have found that women who smoke during pregnancy are 2.6 times more likely to give birth prematurely compared to non-smokers – more than double the previous estimate.

The study, published today in the International Journal of Epidemiology, also found that smoking meant that the baby was four times more likely to be small for its gestational age, putting it at risk of potentially serious complications including breathing difficulties and infections.

But the team found no evidence that caffeine intake was linked to adverse outcomes.

Women are currently recommended to stop smoking and limit their caffeine intake during pregnancy because of the risk of complications ...

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. — Having a chronic illness is a great deal of work, communication researchers have long known. But having an illness that is stigmatized, not well understood or not perceived as a priority by clinicians is uniquely burdensome for many women, who find themselves struggling to establish both the legitimacy of their medical problems and their credibility with clinicians, family members and friends, a recent study suggests.

Sasha, a 25-year-old woman interviewed for the project, told the researchers she has a binder 3 inches thick containing all her medical records that she lugs to every doctor’s appointment to provide documentation ...

The results of the Chi-Nu physics experiment at Los Alamos National Laboratory have contributed essential, never-before-observed data for enhancing nuclear security applications, understanding criticality safety and designing fast-neutron energy reactors. The Chi-Nu project, a years-long experiment measuring the energy spectrum of neutrons emitted from neutron-induced fission, recently concluded the most detailed and extensive uncertainty analysis of the three major actinide elements — uranium-238, uranium-235 and plutonium-239.

“Nuclear fission and related nuclear chain ...