Boreal and temperate forests now main global carbon sinks

2023-10-02

(Press-News.org)

Using a new analysis method for satellite images, an international research team, coordinated by the French Alternative Energies and Atomic Energy Commission (CEA) and INRAE, mapped for the first time annual changes in global forest biomass between 2010 and 2019. Researchers discovered that boreal and temperate forests have become the main global carbon sinks. Tropical forests, which are older and degraded by deforestation, fire and drought, are nearly carbon neutral. The findings, published in Nature Geoscience, highlight the importance of accounting for young forests and forest degradation in predictive carbon‑sink models to develop more effective climate change mitigation strategies.

Increases in plant biomass play an essential role in carbon sequestration to mitigate climate change. The carbon balance of biomass results from gains due to plant growth and increased forest cover and losses due to harvest, deforestation, degradation, background tree mortality and natural disturbances. Monitoring biomass carbon stocks over time is essential to better understand and predict the effects of ongoing and future climate change, as well as the direct impacts of human activities on ecosystems. This is a key issue for climate change mitigation policies.

The vegetation data, obtained from the Soil Moisture and Ocean Salinity (SMOS) satellite using L-band vegetation optical depth (L-VOD) methods, is unique in estimating average above-ground carbon stocks on a global level. However, the widespread application of L-VOD over the entire globe is limited by signal disruption from radio frequency interference from human activities and by L‑VOD sensitivity to vegetative water content. To address these challenges, the researchers developed a double filter that used temporal signal decomposition (seasonal changes, trends, etc.) to offset these effects. Drawing on above-ground biomass data, researchers determined total biomass using a global map, released in 2020, of the ratio between above- and below-ground biomass (such as roots).* They then calculated the spatial and temporal distribution of total live biomass carbon of terrestrial ecosystems from 2010 to 2019, and developed maps of annual biomass carbon change. Researchers used the maps to assess regional carbon budgets (25×25 km plots), attribute carbon losses and gains to forest-cover change caused by fires and land-use change, and investigate how forest age controls terrestrial carbon storage.

Carbon stocks on Earth increased by 500 million tonnes per year over a 10-year period, primarily because of young trees in temperate and boreal forests

Globally, terrestrial biomass carbon stocks increased from 2010 to 2019 by approximately 500 million tonnes of carbon per year. The main contributors to the global carbon sink are boreal and temperate forests, while tropical forests have become small carbon sources because of deforestation and tree mortality following periods of repeated drought. Old-growth tropical forests, where trees average more than 140 years old, are nearly carbon neutral, whereas temperate and boreal forests, where trees are young (less than 50 years) or middle-aged (50–140 years), are the largest carbon sinks. The new findings differ from existing prediction models that show all old-growth forests to be large carbon sinks and do not account for the importance of forest demography or the impact of deforestation and degradation on tropical forests, which are losing biomass.

The findings highlight the importance of accounting for forest degradation and forest age when predicting dynamics of future carbon sinks at global level, and thereby develop better-suited climate change mitigation policies.

END

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2023-10-02

Subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH) is one of the most dangerous cerebrovascular disorders, with as many as 40% of patients dying within one month of the event.

A study recently published in the esteemed Neurology journal investigated whether there are differences in the prognosis of SAH patients between the university hospital districts in Finland. The research dataset was composed of nearly 10,000 SAH cases from 1998 to 2017, including information on patients who died before receiving neurosurgical care.

Prognoses ...

2023-10-02

Mobile phones, smartwatches and earbuds are some gadgets that we carry around physically without much thought. The increasingly digitalised world sees a shrinking gap between human and technology, and many researchers and companies are interested in how technology can be further integrated into our lives.

What if, instead of incorporating technology into our physical world, we assimilate ourselves into a virtual environment? This is what Assistant Professor Xiong Zehui from the Singapore University of Technology ...

2023-10-02

The research teams of Professor René Ketting at the Institute of Molecular Biology (IMB) in Mainz, Germany, and Dr. Sebastian Falk at the Max Perutz Labs in Vienna, Austria, have identified a new enzyme called PUCH, which plays a key role in preventing the spread of parasitic DNA in our genomes. These findings may reveal new insights into how our bodies detect and fight bacteria and viruses to prevent infections.

Our cells are under constant attack from millions of foreign intruders, such as viruses and bacteria. To keep us from getting sick, ...

2023-10-02

UVA Health researchers have developed a powerful new tool to understand how medications affect men and women differently, and that will help lead to safer, more effective drugs in the future.

Women are known to suffer a disproportionate number of liver problems from medications. At the same time, they are typically underrepresented in drug testing. To address this, the UVA scientists have developed sophisticated computer simulations of male and female livers and used them to reveal sex-specific differences in how the tissues are affected by drugs.

The new model has already provided ...

2023-10-02

Using zebrafish as a model, investigators have determined a suitable combination of chemical compounds in which to store hearts, and potentially other organs, when frozen for extended periods of time before transplantation.

The work, which is published in The FASEB Journal, involved a variety of methods, including assays at multiple developmental stages, techniques for loading and unloading agents, and the use of viability scores to quantify organ function.

These methods allowed scientists to perform the largest and most comprehensive screen of cryoprotectant agents to determine their toxicity and efficiency at preserving ...

2023-10-02

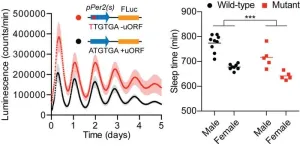

Osaka, Japan - Circadian rhythms, the internal biological clocks that regulate our daily activities, are essential for maintaining health and well-being. While the role of transcription in these rhythms is well-established, a new study sheds light on the critical importance of post-transcriptional processes. The research, titled “Circadian ribosome profiling reveals a role for the Period2 upstream open reading frame in sleep,” to be published in PNAS, redefines our understanding of how translation and post-transcriptional processes influence the body’s internal clock and its impact on sleep patterns.

Timing Is Everything: ...

2023-10-02

Osaka, Japan – Memory B cells depend on autophagy for their survival, but the protein Rubicon is thought to hinder this process. Researchers from Osaka University have discovered a shorter isoform of Rubicon called RUBCN100, which enhances autophagy in B cells. Mice that lacked the longer isoform, RUBCN130, produced more memory B cells in a way that relied on autophagy. These findings provide further insight into the role of Rubicon in autophagy.

Autophagy is a mechanism that degrades and ...

2023-10-02

Until recently, our understanding of Parkinson's disease has been quite limited, which has been apparent in the limited treatment options and management of this debilitating condition.

Our recent understanding has primarily revolved around the genetic factors responsible for familial cases, while the causative factors in the vast majority of patients remained unknown.

However, in a new study, researchers from the University of Copenhagen have unveiled new insights into the workings of the brain in Parkinson's patients. Leading the groundbreaking discovery is Professor Shohreh Issazadeh-Navikas.

“For the first time, we can show that mitochondria, ...

2023-10-02

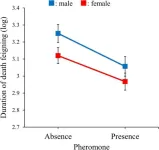

Predation is a driving force in the evolution of anti-predator strategies, and death feigning, characterized by immobility in response to threats, is a common defensive mechanism across various animal species. While this behavior can enhance an individual's survival prospects by reducing a predator's interest, it also carries costs, such as limited opportunities for feeding and reproduction. Recently, researchers from Okayama University, Japan, investigated how pheromones, important chemical signals that affect foraging and reproduction, might influence death-feigning behavior in the red flour beetle, Tribolium castaneum.

“Male beetles release an aggregation pheromone called ...

2023-10-02

Genetic quality or genetic compatibility? What do female fruit flies prioritize when mating? Researchers at the University of Zurich show that both factors are important at different stages of the reproductive process and that females use targeted strategies to optimize the fitness of their offspring.

Breeding female fruit flies face a difficult decision: do they mate with the male that has the best genes, or with the one whose genes best match their own? Evolutionary biologists from the University of Zurich and Concordia University have now investigated ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Boreal and temperate forests now main global carbon sinks