(Press-News.org) Photos

Savannas and grasslands in drier climates around the world store more heat-trapping carbon than scientists thought they did and are helping to slow the rate of climate warming, according to a new study.

The study, published online Oct. 2 in Nature Climate Change, is based on a reanalysis of datasets from 53 long-term fire-manipulation experiments worldwide, as well as a field-sampling campaign at six of those sites.

Twenty researchers from institutions around the globe, including two at the University of Michigan, looked at where and why fire has changed the amount of carbon stored in topsoil. They found that within savanna-grassland regions, drier ecosystems were more vulnerable to changes in wildfire frequency than humid ecosystems.

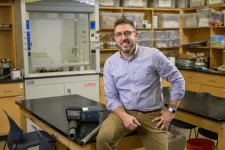

"The potential to lose soil carbon with very high fire frequencies was the greatest in dry areas, and the potential to store carbon when fires were less frequent was also the greatest in dry areas," said study lead author Adam Pellegrini, currently an IGCB Exchange Professor at U-M's Institute for Global Change Biology. His primary appointment is at the University of Cambridge.

Over the last 20 years, fire suppression due to population expansion and landscape fragmentation caused by the introduction of roads, croplands and pastures into savannas and grasslands led to smaller wildfires and less burned areas in drier savannas and grasslands.

In dryland savannas, the reduction in the size and frequency of wildfires has led to an estimated 23% increase in stored topsoil carbon. The increase was not foreseen by most of the state-of-the-art ecosystem models used by climate researchers, according to forest ecologist and study second author Peter Reich, professor and director of the Institute for Global Change Biology at the U-M School for Environment and Sustainability.

As a result, the climate-buffering impacts of dryland savannas have likely been underestimated, Reich said. The new study estimates that soils in savanna-grassland regions worldwide have gained 640 million metric tons of carbon over the past two decades.

"Ongoing declines in fire frequencies have probably created an extensive carbon sink in the soils of global drylands that may have been underestimated by ecosystem models," Reich said. "In other words, in the past couple of decades, global savannas and grasslands have slowed climate warming more than they have accelerated it—despite fires. But there is absolutely no guarantee that will continue in the future."

Savannas are tropical or subtropical grasslands—in eastern Africa, northern South America and elsewhere—that contain scattered trees and drought-resistant undergrowth. The new study looked at recent changes in burned area and fire frequency in savannas, other grasslands, seasonal woodlands and some forests.

Across 888,000 square miles (2.3 million square kilometers) of dryland savanna-grasslands, where fire frequency and burned area declined over the past two decades, soil carbon rose by an estimated 23%.

But in more humid savanna-grassland regions covering 533,000 square miles (1.38 million square kilometers), more frequent wildfires and increased burned area resulted in an estimated 25% loss in soil carbon over the past two decades.

The net change, during that time, was a gain of 0.64 petagrams, or 640 million metric tons, of soil carbon. That works out to a 0.038 petagram (38 million metric ton) increase per year.

"In the grand scheme of things, no, this is not really a massive amount of carbon that will put a dent in heat-trapping anthropogenic emissions," Pellegrini said. "But no one region—neither the Amazon rainforest nor the U.S. Great Plains grasslands nor Canada's boreal forest nor dozens of other biomes around the world—can alone store sufficient carbon to make a large contribution to slowing climate change. However, in aggregate, they can.

"Plus, there are several savanna and grassland regions that have soil carbon-credit projects being developed, so understanding their capacity to sequester carbon is relevant to the region—even if it's not a massive flux globally."

Funding for the study was provided by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, United Kingdom Research and Innovation, Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and U.S. Department of Energy. The Cedar Creek Long Term Ecological Research program in Minnesota was funded by the U.S. National Science Foundation. Sampling at other sites was funded by the U.S. National Park Service, Sequoia Parks Conservancy and South African National Parks.

Study: Soil carbon storage capacity of drylands under altered fire regimes

END

Drier savannas, grasslands store more climate-buffering carbon than previously believed

2023-10-02

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Ancient architecture inspires a window to the future

2023-10-02

A centuries-old technique for constructing arched stone windows has inspired a new way to form tailored nanoscale windows in porous functional materials called metal-organic frameworks (MOFs).

The method uses a molecular version of an architectural arch-forming “centring formwork“ template to direct the formation of MOFs with pore windows of predetermined shape and size.[1]. New MOFs designed and made in this way range from narrow-windowed materials with gas separation potential to larger-windowed structures with potential medical applications due to their excellent oxygen-adsorption capacity.

“One of the most challenging ...

Climate and human land use both play roles in Pacific island wildfires past and present

2023-10-02

DALLAS (SMU) – It’s long been understood that human settlement contributes to conditions that make Pacific Islands more susceptible to wildfires, such as the devastating Aug. 8 event that destroyed the Maui community of Lahaina. But a new study from SMU fire scientist Christopher Roos published in the journal Nature Ecology and Evolution shows that climate is an undervalued part of the equation.

Roos, SMU environmental archaeologist and professor of anthropology, traveled with his team to the Sigatoka ...

DeepMB: a deep learning framework for high-quality optoacoustic imaging in real-time

2023-10-02

Researchers at Helmholtz Munich and the Technical University of Munich have made significant progress in advancing high-resolution optoacoustic imaging for clinical use. Their innovative deep-learning framework, known as DeepMB, holds great promise for patients dealing with a range of illnesses, including breast cancer, Duchenne muscular dystrophy, and inflammatory bowel disease. Their findings have been now published in Nature Machine Intelligence.

In order to understand and detect diseases scientists and medical staff often rely on imaging methods such as ultrasound or X-ray. However, ...

Overlooked parts of proteins revealed as critical to fundamental functions of life

2023-10-02

According to textbooks, proteins work by folding into stable 3D shapes that, like Lego blocks, precisely fit with other biomolecules.

Yet this picture of proteins, the "workhorses of biology," is incomplete. Around half of all proteins have stringy, unstructured bits hanging off them, dubbed intrinsically disordered regions, or IDRs. Because IDRs have more dynamic, “shape-shifting” geometries, biologists have generally thought that they cannot have as precise of a fit with other biomolecules as their folded ...

Not the usual suspects: New interactive lineup boosts eyewitness accuracy

2023-10-02

Allowing eyewitnesses to dynamically explore digital faces using a new interactive procedure can significantly improve identification accuracy compared to the video lineup and photo array procedures used by police worldwide, a new study reveals.

Interactive lineups present digital 3D faces that witnesses can rotate and view from different angles using a computer mouse - enabling witnesses to actively explore and match faces to their recollection.

Publishing their findings today (2 Oct) in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, psychologists found that the interactive procedure enhanced people’s ability to correctly identify perpetrators and avoid misidentifications.

Lead ...

Yang developing training dataset labeling tool

2023-10-02

Chaowei Yang, Professor, Director, NSF Spatiotemporal Innovation Center, Geography and Geoinformation Science, received funding from the National Science Foundation for the project: "I-Corps: An automatic training dataset labeling tool for producing large amount of quality training datasets."

He and his collaborators are interviewing more than 100 potential customers to: a) identify a customer sector that has the potential to show early success, b) define from a customer perspective a Minimum Viable Product (MVP), c) explore the potential and plan to create a startup by a team composed of ...

Loneliness and risk of Parkinson disease

2023-10-02

About The Study: This study of 491,000 participants followed up for up to 15 years found that loneliness was associated with risk of incident Parkinson disease across demographic groups and independent of depression and other prominent risk factors and genetic risk. The findings add to the evidence that loneliness is a substantial psychosocial determinant of health.

Authors: Antonio Terracciano, Ph.D., of the Florida State University College of Medicine in Tallahassee, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2023.3382)

Editor’s ...

Paxlovid and COVID-19 mortality and hospitalization among patients with vulnerability to COVID-19 complications

2023-10-02

About The Study: In this study of 6,866 individuals with COVID-19, nirmatrelvir and ritonavir (Paxlovid [Pfizer]) treatment was associated with reduced risk of COVID-19 hospitalization or death in clinically extremely vulnerable individuals, with the greatest benefit observed in severely immunocompromised individuals. No reduction in the primary outcome (death from any cause or emergency hospitalization with COVID-19 within 28 days) was observed in lower-risk individuals, including those age 70 or older without serious comorbidities.

Authors: Colin R. Dormuth, Sc.D., ...

Discrimination alters brain-gut ‘crosstalk,’ prompting poor food choices and increased health risks

2023-10-02

People frequently exposed to racial or ethnic discrimination may be more susceptible to obesity and related health risks in part because of a stress response that changes biological processes and how we process food cues. These are findings from UCLA researchers conducting what is believed to be the first study directly examining effects of discrimination on responses to different types of food as influenced by the brain-gut-microbiome (BGM) system.

The changes appear to increase activation in regions of the brain associated with reward and self-indulgence – like seeking “feel-good” ...

Tablet-based AI app measures multiple behavioral indicators to screen for autism

2023-10-02

DURHAM, N.C. – Researchers at Duke University have demonstrated an app driven by AI that can run on a tablet to accurately screen for autism in children by measuring and weighing a variety of distinct behavioral indicators.

Called SenseToKnow, the app delivers scores that evaluate the quality of the data analyzed, the confidence of its results and the probability that the child tested is on the autism spectrum. The results are fully interpretable, meaning that they spell out exactly which of the behavioral indicators led to its conclusions and why.

This ability ...