(Press-News.org) Robots built by engineers at the University of California San Diego helped achieve a major breakthrough in understanding how insect flight evolved, described in the Oct. 4, 2023 issue of the journal Nature. The study is a result of a six-year long collaboration between roboticists at UC San Diego and biophysicists at the Georgia Institute of Technology.

The findings focus on how the two different modes of flight evolved in insects. Most insects use their brains to activate their flight muscles each wingstroke, just like we activate the muscles in our legs every stride we take. This is called synchronous flight. But some insects, such as mosquitoes, are able to flap their wings without their nervous system commanding each wingstroke. Instead, the muscles of these animals automatically activate when they are stretched. This is called asynchronous flight. Asynchronous flight is common in some of the insects in the four major insect groups, allowing them to flap their wings at great speeds, allowing some mosquitoes to flap their wings more than 800 times a second, for example.

For years, scientists assumed the four groups of insects–bees, flies, beetles and true bugs (hemiptera)– all evolved asynchronous flight separately. However, a new analysis performed by the Georgia Tech team concludes that asynchronous flight actually evolved together in one common ancestor. Then some groups of insect species reverted back to synchronous flight, while others remained asynchronous.

The finding that some insects such as moths have evolved from synchronous to asynchronous, and then back to synchronous flight led the researchers down a path of investigation that required insect, robot, and mathematical experiments. This new evolutionary finding posed two fundamental questions: do the muscles of moths exhibit signatures of their prior asynchrony and how can an insect maintain both synchronous and asynchronous properties in their muscles and still be capable of flight?

The ideal specimen to study these questions of synchronous and asynchronous evolution is the Hawkmoth. That’s because moths use synchronous flight, but the evolutionary record tells us they have ancestors with asynchronous flight.

Researchers at Georgia Tech first sought to measure whether signatures of asynchrony can be observed in the Hawkmoth muscle. Through mechanical characterization of the muscle they discovered that Hawkmoths still retain the physical characteristics of asynchronous flight muscles–even if they are not used.

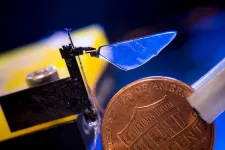

How can an insect have both synchronous and asynchronous properties and still fly? To answer this question researchers realized that using robots would allow them to perform experiments that could never be done on insects. For example, they would be able to equip the robots with motors that could emulate combinations of asynchronous and synchronous muscles and test what transitions might have occurred during the millions of years of evolution of flight.

The work highlights the potential of robophysics–the practice of using robots to study the physics of living systems, said Nick Gravish, a professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering at the UC San Diego Jacobs School of Engineering and one of the paper’s senior authors.

“We were able to provide an understanding of how the transition between asynchronous and synchronous flight could occur,” Gravish said. “By building a flapping wing robot, we helped provide an answer to an evolutionary question in biology.”

Essentially, if you’re trying to understand how animals–or other things–move through their environment, it is sometimes easier to build a robot that has similar features to these things and moves through the same environment, said James Lynch, who earned his Ph.D. in Gravish’s lab and is one of the lead co-authors of the paper.

“One of the biggest evolutionary findings here is that these transitions are occurring in both directions, and that instead of multiple independent origins of asynchronous muscle, there's actually only one,” said Brett Aiello, an assistant professor of biology at Seton Hill University and one of the co-first authors. He did the work for his study when he was a postdoctoral researcher in the lab of Georgia Tech professor Simon Sponberg. “From that one independent origin, multiple revisions back to synchrony have occurred.”

Building robo-physical models of insects

Lynch and co-first author Jeff Gau, a Ph.D. student at Georgia Tech, worked together to study moths and take measurements of their muscle activity under flight conditions. They then built a mathematical model of the moth’s wing flapping movements.

Lynch took the model back to UC San Diego, where he translated the mathematical model into commands and control algorithms that could be sent to a robot mimicking a moth wing. The robots he built ended up being much bigger than moths–and as a result, easier to observe. That’s because in fluid physics, a very big object moving very slowly through a denser medium–in this case water–behaves the same way than a very small object moving much faster through a thinner medium–in this case air.

“We dynamically scaled this robot so that this much larger robot moving much more slowly was representative of a much smaller wing moving much faster,” Lynch said.

The team made two robots: a large flapper robot modeled after a moth to better understand how the wings worked, which they deployed in water. They also built a much smaller flapper robot that operated in air (modeled after Harvard’s robo bee).

Findings, challenges and next steps

The robot and modeling experiments helped researchers test how an insect could transition from synchronous to asynchronous flight. For example, researchers were able to create a robot with motors that could combine synchronous and asynchronous flight and see if it would actually be able to fly. They found that under the right circumstances, an insect could transition between the two modes gradually and smoothly.

“The robot experiments provided a possible pathway for this evolution and transition,” Gravish said.

Lynch encountered several challenges, including modeling the fluid flow around the robots, and modeling the feedback property of insect muscle when it’s stretched. Lynch was able to solve this by simplifying the model as much as possible while making sure it remained accurate. After several experiments, he also realized he would have to slow down the movements of the bots to keep them stable.

Next steps from the robotics perspective will include working with material scientists to equip the flappers with muscle-like materials.

In addition to helping clarify the evolution and biophysics of insect flight, the work has benefits for robotics. Robots with asynchronous motors can rapidly adapt and respond to the environment, such as during a wind-gust or wing collision,Gravish said. The research also could help roboticists design better bots with flapping wings.

“This type of work could help usher in a new era of responsive and adaptive flapping wing systems,” Gravish said.

Biophysical transitions in insect flight dynamics are bridged by common muscle physiology

James Lynch and Nick Gravish, University of California San Diego

Jeff Gau, Brett Aiello, Ethan Wold and Simon Spoonberg, Georgia Institute of Technology

END

These robots helped understand how insects evolved two distinct strategies of flight

2023-10-04

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

New research finds that ancient carbon in rocks releases as much carbon dioxide as the world's volcanoes

2023-10-04

Main points:

New research has overturned the traditional view that natural rock weathering acts as a CO2 sink that removes CO2 from the atmosphere. Instead, this can also act as a large CO2 source, rivalling that of volcanoes.

The results have important implications for modelling climate change scenarios but at the moment, CO2 release from rock weathering is not captured in climate modelling.

Future work will focus on whether human activities may be increasing CO2 release from rock weathering, and how this could be managed.

A new study led by the University of Oxford has overturned the view ...

New "Assembly Theory" unifies physics and biology to explain evolution and complexity

2023-10-04

An international team of researchers has developed a new theoretical framework that bridges physics and biology to provide a unified approach for understanding how complexity and evolution emerge in nature. This new work on "Assembly Theory," published today in Nature, represents a major advance in our fundamental comprehension of biological evolution and how it is governed by the physical laws of the universe.

This research builds on the team's previous work developing Assembly Theory as an empirically validated approach to life detection, ...

Unlocking the secrets of neuronal function: a universal workflow

2023-10-04

Biophysically detailed neuronal models provide a unique window into the workings of individual neurons. They enable researchers to manipulate neuronal properties systematically and reversibly, something that is often impossible in real-world experiments. These in silico models have played a pivotal role in advancing our understanding of how neuronal morphology influences excitability and how specific ion currents contribute to cell function. Additionally, they have been instrumental in building neuronal circuits to simulate and study brain activity, offering ...

Munich neuroscientist receives around 1.5 million euros for research into ALS and FTD

2023-10-04

Dr. Qihui Zhou, a neuroscientist at DZNE’s Munich site, has been awarded a “Starting Grant” from the European Research Council (ERC) worth about 1.5 million euros to investigate disease mechanisms of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and frontotemporal dementia (FTD). With her studies, which will focus on the role of immune cells in the disease process and on the most common genetic forms of ALS and FTD, Zhou aims to pave the way for better treatments.

ALS and FTD are devastating diseases characterized by loss of brain cells for which there ...

INSEAD launches world’s largest XR immersive learning library for management education and research

2023-10-04

First business school to launch comprehensive library of VR Learning Experiences to make management education more impactful and to advance management research

VR Learning Experiences already used by 40+ professors and 13K+ learners at INSEAD and now available globally via the INSEAD XR Portal

Professor Ithai Stern, Academic Director of the INSEAD Immersive Learning Initiative, wins 2023 Strategic Management Society Educational Impact Award for his contribution to quality and innovation of strategic management teaching

Fontainebleau ...

Largest dataset of thousands of proteins marks landmark step for research into human health

2023-10-04

Today, [Wednesday 4 October] the scientific journal Nature1 published the results of the world’s largest and most comprehensive study on the effects of common genetic variation on proteins circulating in the blood and how these associations can contribute to disease. This unprecedented population-scale investigation of proteins, powered by turning biological samples into data from UK Biobank, will help scientists better understand how and why diseases develop, which could help drive the development of new diagnostics and treatments for a wide range of health conditions.

To develop this unique and unparalleled dataset, researchers measured the abundance of nearly ...

Selective removal of aging cells opens new possibilities for treating age-related diseases

2023-10-04

A research team, led by Professor Ja Hyoung Ryu from the Department of Chemistry at UNIST, in collaboration with Professor Hyewon Chung from Konkuk University, has achieved a significant breakthrough in the treatment of age-related diseases. Their cutting-edge technology offers a promising new approach by selectively removing aging cells, without harming normal healthy cells. This groundbreaking development is poised to redefine the future of healthcare and usher in a new era of targeted therapeutic interventions.

Aging cells, known as senescent cells, contribute to various inflammatory conditions and age-related ailments as humans age. To address this issue, the research team focused on ...

CHOP researchers find barriers to driver training and licensure, especially among low-income teens

2023-10-04

Philadelphia, October 2, 2023 – Researchers from the Center for Injury Research and Prevention (CIRP) at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) and the Stuart Weitzman School of Design at the University of Pennsylvania have found that teenagers living in lower-income areas of the Columbus, Ohio metro area are up to four times less likely to complete driver training and obtain their driver’s license before age 18. Long travel times to driving schools also impacted enrollment in driver education, affecting those from both higher- and lower-income areas.

The findings, originally published in the journals Accident Analysis and Prevention ...

Vulnerability found in immunotherapy-resistant triple-negative breast cancer

2023-10-04

Researchers at Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center have discovered a druggable target on natural killer cells that could potentially trigger a therapeutic response in patients with immunotherapy-resistant, triple-negative breast cancer.

Currently, only about 15% of early-stage, triple-negative breast cancer patients benefit from combining immunotherapy, drugs that target immune cells to attack the tumor, with chemotherapy. Identifying why most patients don’t respond is critical for personalizing treatment plans and minimizing therapy ...

Discovery of massive undersea water reservoir could explain New Zealand’s mysterious slow earthquakes

2023-10-04

Researchers have discovered a sea’s worth of water locked within the sediment and rock of a lost volcanic plateau that’s now deep in the Earth’s crust. Revealed by a 3D seismic image, the water lies two miles under the ocean floor off the coast of New Zealand, where it may be dampening a major earthquake fault that faces the country’s North Island.

The fault is known for producing slow-motion earthquakes, called slow slip events. These can release pent-up tectonic pressure harmlessly over days and weeks. Scientists want to know why they happen more often at some ...