But a new study suggests that might not be enough. It turns out indirect media exposure, i.e., having friends who watch a lot of TV, might be even more damaging to a teenager's body image.

Researchers from Harvard Medical School's Department of Global Health and Social Medicine examined the link between media consumption and eating disorders among adolescent girls in Fiji.

What they found was surprising. The study's subjects did not even need to have a television at home to see raised risk levels of eating disorder symptoms.

In fact, by far the biggest factor for eating disorders was how many of a subject's friends and schoolmates had access to TV. By contrast, researchers found that direct forms of exposure, like personal or parental viewing, did not have an independent impact, when factors like urban location, body shape and other influences were taken into account.

It appeared that changing attitudes within a group that had been exposed to television were a more powerful factor than actually watching the programs themselves. In fact, higher peer media exposure were linked to a 60 percent increase in a girl's odds of having a high level of eating disorder symptoms, independently of her own viewing.

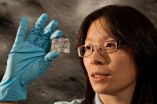

Lead author Anne Becker, vice chair of the Department of Global Health and Social Medicine at Harvard Medical School, said this was the first study to attempt to quantify the role of social networks in spreading the negative consequences of media consumption on eating disorders.

"Our findings suggest that social network exposure is not just a minor influence on eating pathology here, but rather, IS the exposure of concern," she said.

"If you are a parent and you are concerned about limiting cultural exposure, it simply isn't going to be enough to switch off the TV. If you are going to think about interventions, it would have to be at a community or peer-based level."

Becker hopes the paper will encourage debate about responsible programming and the regulation of media content to prevent children from secondhand exposure.

"Up until now, it has been very difficult to get people who produce media as entertainment to come to the table and think about how they might ensure that their products are not harmful to children," she said.

This is Becker's second study of media's impact in Fiji, which is an ideal location for broadcast media research because of the recent arrival of television, in the 1990s, and the significant regional variations in exposure to TV, the Internet and print media. Some remote areas in the recent study still did not have electricity, cell phone reception, television or the Internet when the data were collected in 2007.

Her first study found a rise in eating disorder symptoms among adolescent girls following the introduction of broadcast television to the island nation in 1995.

What makes Fiji a particularly interesting case is that traditional culture prizes a robust body shape, in sharp contrast to the image presented by Western television shows such as Beverly Hills 90210, Seinfeld and Melrose Place, which were quite popular in Fiji when television debuted there in the 1990s.

Girls would see actresses as role models, says Becker, and began noting how a slender body shape was often accompanied by success in those shows. This perception appears to have been one of the factors leading to a rise in eating pathology among the Fijian teenagers.

But until now, it was not known how much of this effect came from an individual's social network.

Nicholas Christakis, professor of medical sociology in the department of health care policy at Harvard Medical School, has studied the spread of health problems through social networks.

"It shouldn't be that surprising to us, even though it is intriguing, that the indirect effects of media are greater," Christakis said. "Most people aren't paying attention to the media, but they are paying attention to what their friends say about what's in the media. It's a kind of filtration process that takes place by virtue of our social networks."

Becker says that although the study focused on Fijian schoolgirls, remote from the US, it warrants concern and further investigation of the health impact on other populations.

INFORMATION:

This research was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health, Harvard University and the Radcliffe Institute.

Written by Kit Chellel

Full citation:

The British Journal of Psychiatry (2011), 198, 43-50

"Social network media exposure and adolescent eating pathology in Fiji"

Anne E. Becker(1), Kristen E. Fay(2), Jessica Agnew-Blais(3), A. Nisha Khan(4), Ruth H. Striegel-Moore(5) and Stephen E. Gilman(6)

1-Anne E. Becker, MD, PhD, ScM, Department of Global Health and Social Medicine, Harvard Medical School and Department of Psychiatry, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, USA;

2-Kristen E. Fay, MA, Eliot-Pearson Department of Applied Child Development, Tufts University, Medford, USA;

3-Jessica Agnew-Blais, ScM, Department of Epidemiology, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston;

4-A. Nisha Khan, Ministry of Health, Suva, Fiji;

5-Ruth H. Striegel-Moore, PhD, Department of Psychology, Wesleyan University, Middletown, USA;

6-Stephen E. Gilman, ScD, Department of Epidemiology and Department of Society, Human Development & Health, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, USA

Harvard Medical School has more than 7,500 full-time faculty working in 11 academic departments located at the School's Boston campus or in one of 47 hospital-based clinical departments at 17 Harvard-affiliated teaching hospitals and research institutes. Those affiliates include Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Brigham and Women's Hospital, Cambridge Health Alliance, Children's Hospital Boston, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Forsyth Institute, Harvard Pilgrim Health Care, Hebrew SeniorLife, Joslin Diabetes Center, Judge Baker Children's Center, Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary, Massachusetts General Hospital, McLean Hospital, Mount Auburn Hospital, Schepens Eye Research Institute, Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital, and VA Boston Healthcare System.

END