(Press-News.org) When targeting problem proteins involved in causing or spreading disease, a drug will often clog up a protein’s active site so it can’t function and wreak havoc. New strategies for dealing with these proteins can send these proteins to different types of cellular protein degradation machinery such as a cell’s lysosomes, which act like a protein wood chipper.

In a new study published in Science on Oct. 20, Stanford chemists have uncovered how one of the pathways leading to this protein “wood chipper” works. In doing so, they have opened the door to new therapeutics for age-related disorders, autoimmune diseases, and treatment-resistant cancers. These findings may also improve therapeutics for lysosomal storage disorders, which are rare but often serious conditions mostly affecting babies and children.

“Understanding exactly how proteins are shuttled to lysosomes to be broken down can help us harness the innate power of a cell to get rid of proteins that cause the human body so much harm,” said Carolyn Bertozzi, the Anne T. and Robert M. Bass Professor in the School of Humanities and Sciences and Baker Family Director of Sarafan ChEM-H. “The work done here is a clear look into a typically opaque intracellular process, and it’s shining a light on a new world of possible drug discovery.”

“The ability to understand the biology of this process means we can use inherent biology that already exists, and harness it to treat disease,” said Steven Banik, assistant professor of chemistry in the School of Humanities and Sciences. “These insights offer a unique window into a new type of biology that we haven’t really understood before.”

Stopping proteins from going rogue

While proteins often do a body good, like help us digest our food or repair torn muscles, they can also be destructive. In cancer, for example, proteins can either become part of the tumor and/or allow for its unchecked growth, cause devastating diseases like Alzheimer’s, and build up in the heart to affect how it pumps blood to the rest of the body.

To stop rogue proteins, drugs can be deployed to block a protein’s active site and thus stop it from interacting with a cell, which was the standard of therapeutic research for decades. Then 20 years ago, proteolysis targeting chimeras (PROTACs) burst onto the scene, which can engage bad-acting proteins that are already inside a cell, and send them off to be broken down in the lysosome.

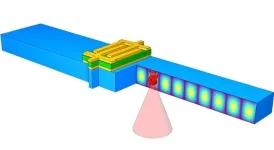

PROTACs are currently in clinical trials and have shown efficacy in treating cancer. But they can only target a protein if it is inside the cell, which is only 60% of the time. In 2020, Stanford ChEM-H researchers pioneered a way to reach the other 40% of those proteins through lysosome targeting chimeras (LYTACs), which can identify and mark proteins that are hanging out around the cell, or on a cell’s membrane, for destruction.

These findings kicked off a new class of research and therapeutics, but exactly how the process worked wasn’t clear. Researchers also noticed that it was difficult to predict when LYTACs would be highly successful or fail to perform as anticipated.

New therapeutic targets

In this work, Green Ahn, PhD, then a Stanford graduate student and now a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Washington Institute for Protein Design, and lead author on the study, used a genetic CRISPR screen to identify and characterize the cellular components that modulate how LYTACs degrade proteins. Through this screening, the team identified a link between the level of neddylated cullin 3 (CUL3) – a protein that plays a housekeeping role in breaking down cellular proteins – and LYTAC efficacy. The exact tie isn’t clear yet, but the more neddylated CUL3 present, the more effective LYTACs were.

Measuring the level of neddylated CUL3 could be a test given to determine which patients are more likely to respond to LYTAC therapy. This was a surprise finding, said Bertozzi, as no previous research pointed to this correlation before.

They also identified proteins that block LYTACs from doing their job. LYTACs work by binding to certain receptors on the outside of the cell, which they use to shuttle bad proteins into lysosomes for degradation. However, the researchers saw that proteins bearing mannose 6-phosphates (M6Ps), sugars that decorate proteins destined for lysosomes, will take a seat on those receptors, meaning LYTACs have nowhere to bind. By throwing a wrench into M6P biosynthesis, an increased fraction of unoccupied receptors resulted on the cell surface which could be hijacked by LYTACs.

New biology, new pathways for treatment of disease

In addition to helping develop LYTACs into more effective therapeutics, these discoveries could also lead to new and more effective treatments for lysosome shortage disorders – genetic conditions where the body doesn’t have enough or the right enzymes in lysosomes for them to work properly. This can cause toxic build ups of fat, sugars, and other harmful substances, which can lead to heart, brain, skin, and skeletal damage. One common treatment is enzyme replacement therapy, which utilizes similar pathways as LYTACs to travel to lysosomes where they can operate. Understanding how and why LYTACs work means that these enzymes could be delivered more effectively.

The researchers likened this work to an important discovery of how exactly the drug thalidomide works. It was originally prescribed in the 1950s for morning sickness to pregnant women, mostly in the United Kingdom, but was taken off the market in 1961 when it was linked to severe birth defects. However, in the 1990s, it was found to be an effective treatment for multiple myeloma. In 2010, researchers understood how: through degrading proteins, an observation which contributed substantially to the growing field of PROTAC research.

“LYTAC evolution is where the story of thalidomide and PROTACs was 15 years ago,” Bertozzi said. “We’re learning human biology that wasn’t known before.”

Other Stanford co-authors include former postdoctoral fellows Nicholas Riley and Roarke Kamber, PhD candidate Salvador Moncayo von Hase, and Michael Bassik, associate professor of genetics in the School of Medicine. Simon Wisnovsky of the University of British Columbia is also a co-author. Banik is an institute scholar at Sarafan ChEM-H and a member of the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute and Stanford Bio-X. Bassik is a member of Bio-X, the Stanford Cancer Institute, the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute, and Sarafan ChEM-H. Bertozzi is a member of the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute, Bio-X, the Stanford Cancer Institute, and the Maternal & Child Health Research Institute (MCHRI), as well as an investigator at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health, the National Science Foundation, the Stanford Center for Molecular Analysis and Design, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, the Cancer Research Society, and the Canadian Glycomics Network, and the Burroughs Wellcome Fund. Bertozzi is the founder of Lycia Therapeutics, where Banik is also on the Scientific Advisory board.

END

Unlocking pathways to break down problem proteins presents new treatment opportunities

2023-10-25

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Using sound to test devices, control qubits

2023-10-25

Acoustic resonators are everywhere. In fact, there is a good chance you’re holding one in your hand right now. Most smart phones today use bulk acoustic resonators as radio frequency filters to filter out noise that could degrade a signal. These filters are also used in most Wi-Fi and GPS systems.

Acoustic resonators are more stable than their electrical counterparts, but they can degrade over time. There is currently no easy way to actively monitor and analyze the degradation of the material quality of these widely used devices.

Now, researchers at the Harvard John ...

Oregon State researchers uncover mechanism for treating dangerous liver condition

2023-10-25

CORVALLIS, Ore. – A study spearheaded by Oregon State University has shown why certain polyunsaturated fatty acids work to combat a dangerous liver condition, opening a new avenue of drug research for a disease that currently has no FDA-approved medications.

Scientists led by Oregon State’s Natalia Shulzhenko, Andrey Morgun and Donald Jump used a technique known as multi-omic network analysis to identify the mechanism through which dietary omega 3 supplements alleviated nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, usually abbreviated to NASH.

The mechanism involves ...

More than just carbs: starchy vegetables play an integral role in meeting nutrition needs

2023-10-25

A perspective recently published in Frontiers in Nutrition underscores the unique role starchy vegetables play as a vital vehicle for essential nutrients. The Dietary Guidelines for Americans currently recommend that most adults consume five to six cups (or cup equivalents) of starchy vegetables each week to help meet their total vegetable goals.1 Yet, as confusion around “good versus bad carbs” persists among consumers, there is a risk of starchy vegetable avoidance in favor of other carbohydrate foods perceived as ...

Study suggests that having common ancestors can jeopardize fertility for generations

2023-10-25

When it comes to the architecture of the human genome, it’s only a matter of time before harmful genes — genes that could compromise future generations — arise in a population. These mutations accumulate in the gene pool, primarily affected by a population’s size and practices like marrying within a small community, according to researchers.

But much of the information about the effects of a population’s mutation load is based on genetic theory, with limited direct evidence concerning the effects on evolutionary fitness, or fertility.

New research from University ...

Zooming in on our brains on Zoom

2023-10-25

New Haven, Conn. — When Yale neuroscientist Joy Hirsch used sophisticated imaging tools to track in real time the brain activity of two people engaged in conversation, she discovered an intricate choreography of neural activity in areas of the brain that govern social interactions. When she performed similar experiments with two people talking on Zoom, the ubiquitous video conferencing platform, she observed a much different neurological landscape.

Neural signaling during online exchanges was substantially suppressed compared to activity observed ...

Breaking down the bias: the portrayals of women in medicine in films

2023-10-25

In the 2009 film "Gifted Hands," based on a true story, the audience follows Black neurosurgeon Dr. Ben Carson as he successfully performs three risky surgeries, earning praise from the media and medical community. This movie was not only a hit with critics and audiences, but it also inspired Bismarck Christian Odei, MD, an assistant professor in radiation oncology at Huntsman Cancer Institute at the University of Utah, to follow his passion.

“Seeing a physician who looked like me, ...

Many in law enforcement own firearms. They are more likely to have suicidal thoughts

2023-10-25

Law enforcement officers in the United States own firearms at high rates and rarely engage in secure firearm storage, which could increase their risk for suicide, according to a Rutgers study.

The researchers, whose study appears in the journal Injury Prevention, examined data from 369 law enforcement officers in the U.S. Information about firearm ownership, storage, suicide risk and demographics were included in the present study.

Overall, 70.5 percent of law enforcement officers report owning a firearm. The most common type of firearms owned were handguns (79.7 percent) followed by shotguns (61.1 percent) and rifles (57.5 percent). A sharp majority, 78.9 percent, ...

Rider on the storm: Shearwater seabird catches an 11 hour ride over 1,000 miles in a typhoon

2023-10-25

New research from Japan published in the Ecological Society of America’s journal Ecology suggests that increasingly severe weather driven by climate change may push oceangoing seabirds to their limits.

In August 2019, Kozue Shiomi, a seabird biologist at Tohoku University, attached GPS bio-loggers to 14 adult streaked shearwaters (Calonectris leucomelas) from a nesting colony on Mikurajima, a small island near Tokyo, as part of a study on the species homing behavior.

In September of that same year, an exceptionally powerful storm, Typhoon Faxai, barreled into southeastern Japan, causing considerable physical damage to the mainland. But the typhoon, ...

Morris Animal Foundation-backed research illuminates path to sihek revival

2023-10-25

DENVER/Oct. 25, 2023 – A recently published paper in Animal Conservation provides crucial insights into the health of sihek, a species eradicated from its native habitat and that may now face threats in captivity. The latest data underscores a stark gender disparity, revealing that female sihek are at greater risk for death and disease than their male counterparts.

As part of an ongoing Morris Animal Foundation-funded study, researchers at The Zoological Society ...

Can insomnia treatment reduce cardiovascular disease risks? $3 million funds study to find out

2023-10-25

INDIANAPOLIS — It’s no secret that a good night’s rest can do wonders for one’s health, but those who struggle with insomnia have a nearly 50% increased risk of cardiovascular disease. One scientist in the School of Science at IUPUI will spend the next five years trying to figure out how those risks can be reduced.

Jesse Stewart, a professor of psychology at the school, has received a five-year, $3 million grant from the National Institutes of Health’s National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute for a project named the Strengthening Hearts ...