(Press-News.org) A new study from the University of Wisconsin–Madison suggests that chemotherapy may not be reaching its full potential, in part because researchers and doctors have long misunderstood how some of the most common cancer drugs actually ward off tumors.

For decades, researchers have believed that a class of drugs called microtubule poisons treat cancerous tumors by halting mitosis, or the division of cells. Now, a team of UW–Madison scientists has found that in patients, microtubule poisons don't actually stop cancer cells from dividing. Instead, these drugs alter mitosis — sometimes enough to cause new cancer cells to die and the disease to regress.

Cancers grow and spread because cancerous cells divide and multiply indefinitely, unlike normal cells which are limited in the number of times they can split into new cells. The assumption that microtubule poisons stop cancer cells from dividing is based on lab studies demonstrating just that.

The new study was led by Beth Weaver, a professor in the departments of oncology and cell and regenerative biology, in collaboration with Mark Burkard in the departments of oncology and medicine. Published Oct. 26 in the journal PLOS Biology and supported in part by the National Institutes of Health, the study broadens previous findings the group made about a specific microtubule poison called paclitaxel. Sometimes prescribed under the brand name Taxol, paclitaxel is used to treat common malignancies including those originating in the ovaries and lungs.

"This was sort of mind-blowing," Weaver says about the previous research. "For decades, we all thought that the way paclitaxel works in patient tumors is by arresting them in mitosis. This is what I was taught as a graduate student. We all 'knew' this. In cells in a dish, labs all over the world have shown this. The problem was we were all using it at concentrations higher than those that actually get into the tumor."

Weaver and her colleagues wanted to know if other microtubule poisons work the same way as paclitaxel — not by stopping mitosis but by messing it up.

The question has significant implications for scientists searching for new cancer treatments. That's because drug discovery efforts often hinge on identifying, reproducing and improving upon the mechanisms believed to be responsible for a compound's therapeutic effect.

While microtubule poisons are no panacea, they are effective for many patients, and researchers have long sought to develop other therapies that mimic what they believe the drugs do. These efforts are ongoing even though past attempts to identify new compounds that treat cancer by stopping cell division have reached frustrating dead ends.

"There's still a lot of the scientific community that's investigating mitotic arrest as a mechanism to kill tumors," Weaver says. "We wanted to know — does that matter for patients?"

With Burkard, the team studied tumor samples taken from breast cancer patients who received standard anti-microtubule chemotherapy at the UW Carbone Cancer Center.

They measured how much of the drugs made it into the tumors and studied how the tumor cells responded. They found that while the cells continued to divide after being exposed to the drug, they did so abnormally. This abnormal division can lead to tumor cell death.

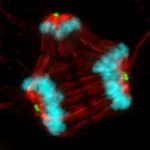

Normally, a cell's chromosomes are duplicated before the two identical sets migrate to opposite ends of the cell mitosis in a process called chromosomal segregation. One set of chromosomes is sorted into each of two new cells.

This migration occurs because the chromosomes are attached to a cellular machine known as the mitotic spindle. Spindles are made from cellular building blocks called microtubules. Normal spindles have two ends, known as spindle poles.

Weaver and her colleagues found that paclitaxel and other microtubule poisons cause abnormalities that lead cells to form three, four or sometimes five poles during mitosis even as they continue to make just one copy of chromosomes. These poles then attract the two complete sets of chromosomes in more than two directions, scrambling the genome.

“So, after mitosis you have daughter cells that are no longer genetically identical and have lost chromosomes," Weaver says. "We calculated that if a cell loses at least 20% of its DNA content, it is very likely going to die."

These findings reveal the likely reason why microtubule poisons are effective for many patients. Importantly, they also help explain why attempts to find new chemo drugs based solely on stopping mitosis have been so disappointing, Weaver says.

"We've been barking up the wrong tree," she says. "We need to refocus our efforts on screwing up mitosis — on making chromosomal segregation worse."

This research was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (P30 CA014520; R01CA234904; T32 GM008688; T32 CA009135; F31CA254247; T32 GM141013).

END

Common chemotherapy drugs don't work like doctors thought, with big implications for drug discovery

Findings reveal the likely reason why certain chemotherapies are effective for many patients. Importantly, they also help explain why attempts to find new chemo drugs based solely on stopping cellular division have been so disappointing.

2023-10-27

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

SynGAP Research Fund awards $100,000 for investigating the impact of SYNGAP1 missense variants using structural bioinformatics

2023-10-26

TURKU, Finland – October 27, 2023 – The SynGAP Research Fund 501(c)(3) announced a $100,000 grant to researchers Pekka Postila and Olli Pentikäinen from the Institute of Biomedicine and InFLAMES Flagship at the University of Turku. Prof. Pentikäinen’s research focuses on molecular modeling and computer-aided drug discovery. Assoc. Prof. Postila is an expert on advanced molecular dynamics simulations of complex biomolecular systems. The dual research team was formed to study the structural effects of missense variants on the SynGAP protein, whose normal functioning ...

Something to chew on: Researchers look for connections in how animals eat and digest food

2023-10-26

Oct. 26, 2023

Media contacts:

Emily Gowdey-Backus, director of media relations, Emily_GowdeyBackus@uml.edu

Nancy Cicco, assistant director of media relations, Nancy_Cicco@uml.edu

UMass Lowell’s Nicolai Konow wants to bridge the gap between research on food processing and nutrient absorption.

“There is a divide between biomechanists, who study chewing and food transport, and physiologists, who examine what actually happens to food in the gastrointestinal tract,” said the assistant professor ...

Viral reprogramming of cells increases risk of cancers in HIV patients

2023-10-26

Viral infections are known to be a central cause of more than 10% of cancers worldwide. University of California researchers may have uncovered one of the key reasons why. Their findings were published today in PLOS Pathogens, a journal that reports groundbreaking work to advance understanding of how pathogens impact diseases such as cancer.

UC Davis Comprehensive Cancer Center researcher Yoshihiro Izumiya teamed up with Michiko Shimoda, who previously worked in the Izumiya Lab at UC Davis. Currently, she is a member of the Core Immunology Lab at UC San Francisco. Together, they led UC Davis researchers in the study of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV). The ...

Robot stand-in mimics movements in VR

2023-10-26

Media Note: Pictures of VRoxy can be viewed and downloaded here: https://cornell.box.com/v/VRoxyrobotproxy

ITHACA, N.Y. – Researchers from Cornell and Brown University have developed a souped-up telepresence robot that responds automatically and in real-time to a remote user’s movements and gestures made in virtual reality.

The robotic system, called VRoxy, allows a remote user in a small space, like an office, to collaborate via VR with teammates in a much larger space. VRoxy represents the latest in remote, robotic embodiment.

Donning a VR headset, a user has access to two view modes: Live mode shows an immersive image of the ...

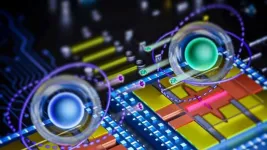

Major milestone achieved in new quantum computing architecture

2023-10-26

Coherence stands as a pillar of effective communication, whether it is in writing, speaking or information processing. This principle extends to quantum bits, or qubits, the building blocks of quantum computing. A quantum computer could one day tackle previously insurmountable challenges in climate prediction, material design, drug discovery and more.

A team led by the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Argonne National Laboratory has achieved a major milestone toward future quantum computing. They have extended the coherence time for their novel type of qubit to an impressive 0.1 milliseconds — nearly a thousand times better than the previous record.

“Rather ...

"Recognition of human right to the environment can galvanize action and collaboration towards realization of sustainable development goals," eminent environmental lawyer says

2023-10-26

Amsterdam, October 26, 2023 – "The Human Right to the Environment affirms the right to life itself. When humans protect nature, they are also securing human health and wellbeing." An article by eminent environmental lawyer Prof. Nicholas A. Robinson sees the recognition of the Human Right to the Environment (HRE) as a first step in a long process of restoring a healthy environment for people and the planet.

Professor Robinson’s article is published in a special issue of the Journal of Environmental Policy and Law on The Human Right to Sustainable Environment. In the preface Editor-in-Chief Bharat H. Desai, PhD, Jawaharlal Nehru University, Centre ...

New tool measures food security duration, severity

2023-10-26

ITHACA, N.Y. – Researchers from the Charles H. Dyson School of Applied Economics and Management have developed a new method for measuring food insecurity, which for millions of people in the U.S. is more than just an abstract concept.

The group’s probability of food security (PFS) measures the likelihood that a household’s food expenditures equal or exceed the minimum cost of a healthful diet. The researchers then put the PFS to the test, analyzing food security dynamics over a recent 17-year period, and found that a third of U.S. households experienced at least temporary food insecurity.

Seungmin Lee, a doctoral student in the field of applied economics and management, ...

Excess fluoride linked to cognitive impairment in children

2023-10-26

Long-term consumption of water with fluoride levels far above established drinking water standards may be linked to cognitive impairments in children, according to a new pilot study from Tulane University.

The study, published in the journal Neurotoxicology and Teratology, was conducted in rural Ethiopia where farming communities use wells with varying levels of naturally occurring fluoride ranging from 0.4 to 15.5 mg/L. The World Health Organization recommends fluoride levels below 1.5 mg/L.

Researchers ...

Scientists find two ways that hurricanes rapidly intensify

2023-10-26

Contacts:

David Hosansky, UCAR/NCAR Manager of Media Relations

hosansky@ucar.edu

720-470-2073

Audrey Merket, UCAR/NCAR Science Writer and Public Information Officer

amerket@ucar.edu

303-497-8293

Hurricanes that rapidly intensify for mysterious reasons pose a particularly frightening threat to those in harm’s way. Forecasters have struggled for many years to understand why a seemingly commonplace tropical depression or tropical storm sometimes blows up into a major hurricane, packing catastrophic winds and driving a potentially deadly surge of water ...

Is red meat intake linked to inflammation?

2023-10-26

Inflammation is a risk factor for many chronic diseases, including cardiovascular disease (CVD), and the impact of diet on inflammation is an area of growing scientific interest. In particular, recommendations to limit red meat consumption are often based, in part, on old studies suggesting that red meat negatively affects inflammation – yet more recent studies have not supported this.

“The role of diet, including red meat, on inflammation and disease risk has not been adequately studied, which can lead to public health recommendations that are not based on strong evidence,” said Dr. Alexis Wood, associate professor of pediatrics – ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Towards unlocking the full potential of sodium- and potassium-ion batteries

UC Irvine-led team creates first cell type-specific gene regulatory maps for Alzheimer’s disease

Unraveling the mystery of why some cancer treatments stop working

From polls to public policy: how artificial intelligence is distorting online research

Climate policy must consider cross-border pollution “exchanges” to address inequality and achieve health benefits, research finds

What drives a mysterious sodium pump?

Study reveals new cellular mechanisms that allow the most common chronic cardiac arrhythmia to persist in the heart

Scientists discover new gatekeeper cell in the brain

High blood pressure: trained laypeople improve healthcare in rural Africa

Pitt research reveals protective key that may curb insulin-resistance and prevent diabetes

Queen Mary research results in changes to NHS guidelines

Sleep‑aligned fasting improves key heart and blood‑sugar markers

Releasing pollack at depth could benefit their long-term survival, study suggests

Addictive digital habits in early adolescence linked to mental health struggles, study finds

As tropical fish move north, UT San Antonio researcher tracks climate threats to Texas waterways

Rich medieval Danes bought graves ‘closer to God’ despite leprosy stigma, archaeologists find

Brexpiprazole as an adjunct therapy for cognitive dysfunction in schizophrenia

Applications of endovascular brain–computer interface in patients with Alzheimer's disease

Path Planning Transformers supervised by IRRT*-RRMS for multi-mobile robots

Nurses can deliver hospital care just as well as doctors

From surface to depth: 3D imaging traces vascular amyloid spread in the human brain

Breathing tube insertion before hospital admission for major trauma saves lives

Unseen planet or brown dwarf may have hidden 'rare' fading star

Study: Discontinuing antidepressants in pregnancy nearly doubles risk of mental health emergencies

Bipartisan members of congress relaunch Congressional Peripheral Artery Disease (PAD) Caucus with event that brings together lawmakers, medical experts, and patient advocates to address critical gap i

Antibody-drug conjugate achieves high response rates as frontline treatment in aggressive, rare blood cancer

Retina-inspired cascaded van der Waals heterostructures for photoelectric-ion neuromorphic computing

Seashells and coconut char: A coastal recipe for super-compost

Feeding biochar to cattle may help lock carbon in soil and cut agricultural emissions

Researchers identify best strategies to cut air pollution and improve fertilizer quality during composting

[Press-News.org] Common chemotherapy drugs don't work like doctors thought, with big implications for drug discoveryFindings reveal the likely reason why certain chemotherapies are effective for many patients. Importantly, they also help explain why attempts to find new chemo drugs based solely on stopping cellular division have been so disappointing.