(Press-News.org) Contacts:

David Hosansky, UCAR/NCAR Manager of Media Relations

hosansky@ucar.edu

720-470-2073

Audrey Merket, UCAR/NCAR Science Writer and Public Information Officer

amerket@ucar.edu

303-497-8293

Hurricanes that rapidly intensify for mysterious reasons pose a particularly frightening threat to those in harm’s way. Forecasters have struggled for many years to understand why a seemingly commonplace tropical depression or tropical storm sometimes blows up into a major hurricane, packing catastrophic winds and driving a potentially deadly surge of water toward shore.

Now scientists have shed some light on why this forecasting challenge has been so difficult to overcome: there’s more than one mechanism that causes rapid intensification. New research by scientists at the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) uses the latest computer modeling techniques to identify two entirely different modes of rapid intensification. The findings may lead to better understanding and prediction of these dangerous events.

“Trying to find the holy grail behind rapid intensification is the wrong approach because there isn’t just one holy grail,” said NCAR scientist Falko Judt, lead author of the new study. “There are at least two different modes or flavors of rapid intensification, and each one has a different set of conditions that must be met in order for the storm to strengthen so quickly.”

One of the modes discussed by Judt and his co-authors occurs when a hurricane intensifies symmetrically, fueled by favorable environmental conditions such as warm surface waters and low wind shear. This type of abrupt strengthening is associated with some of the most destructive storms in history, such as Hurricanes Andrew, Katrina, and Maria. Meteorologists were stunned this week when the winds of Hurricane Otis defied predictions and exploded by 110 miles per hour in just 24 hours, plowing into the west coast of Mexico at category 5 strength.

Judt and his co-authors also identified a second mode of rapid intensification that had previously been overlooked because it doesn’t lead to peak winds reaching such destructive levels. In the case of this mode, the strengthening can be linked to major bursts of thunderstorms far from the storm’s center. These bursts trigger a reconfiguration of the cyclone's circulation, enabling it to intensify rapidly, reaching category 1 or 2 intensity within a matter of hours.

This second mode is more unexpected because it typically occurs in the face of unfavorable conditions, such as countervailing upper-level winds that shear the storm by blowing the top in a different direction than the bottom.

“Those storms are not as memorable and they’re not as significant,” Judt said. “But forecasters need to be aware that even a storm that’s strongly sheared and asymmetric can undergo a mode of rapid intensification.”

The new study appeared in the Monthly Weather Review, a journal of the American Meteorological Society. It was funded by the U.S. Navy Office of Naval Research and by the U.S. National Science Foundation, which is NCAR’s sponsor. It was co-authored by NCAR scientists Rosimar Rios-Berrios and George Bryan.

A serendipitous finding

Rapid intensification occurs when the winds of a tropical cyclone increase by 30 knots (about 35 miles per hour) in a 24-hour period. Judt came across the two modes of rapid intensification when working on an unrelated project.

The discovery emerged after Judt produced a very high-resolution, 40-day computer simulation of the global atmosphere, using the NCAR-based Model for Prediction Across Scales (MPAS). That simulation, run at the NCAR-Wyoming Supercomputing Center, was designed for an international project comparing the output of leading atmospheric models, which have achieved unprecedented detail because of increasingly powerful supercomputers.

Once Judt produced the model, he was curious to examine storms in the simulation that rapidly intensified. By looking at a number of cases across the world’s ocean basins, he noticed that rapid intensification occurred in two distinct ways. This had not previously been apparent in models, partly because previous simulations captured only individual regions instead of allowing scientists to track a spectrum of hurricanes and typhoons across the world’s oceans.

Judt and his co-authors then combed through actual observations of tropical cyclones and found a number of real-world instances of both modes of rapid intensification.

“It was kind of a serendipitous finding,” Judt said. “Just by looking at the storms in the simulation and making plots, I realized that storms that rapidly intensify fall into two different camps. One is the canonical mode in which there’s a tropical storm when you go to bed and when you wake up it’s a category 4. But then there’s another mode that goes from a tropical storm to a category 1 or 2, and it fits the definition of rapid intensification. Since nobody has those storms on their radar, that mode of rapid intensification went undetected until I went through the simulation.”

Meteorologists have long known that favorable environmental conditions, including very warm surface waters and minimal wind shear, can generate rapid intensification and bring a cyclone to category 4 or 5 strength with sustained winds of 130 mph or higher. In their new paper, Judt and his co-authors referred to that mode of rapid intensification as a marathon because the storm keeps intensifying symmetrically at a moderate pace while the primary vortex steadily amplifies.

Judt described Hurricane Otis as a fast marathon because it intensified symmetrically but at an unusually rapid pace, marked by an 80 mph increase in wind speed during a 12-hour period.

The study team labeled the other mode of rapid intensification as a sprint because the intensification is extremely quick but generally doesn’t last as long, with storms peaking at category 1 or 2 strength and sustained winds of 110 mph or less. In such cases, explosive bursts of thunderstorms lead to a rearrangement of the cyclone and the emergence of a new center, enabling the storm to become more powerful — even in the face of adverse environmental conditions.

The paper concludes that the two modes may represent opposite ends of a spectrum, with many cases of rapid intensification falling somewhere in between. For instance, rapid intensification may begin with a chain of discrete events such as a burst of thunderstorms that are characteristic of the sprint mode, but then transition into a more symmetrical mode of intensification that is characteristic of the marathon mode.

A question for future research is why bursts of thunderstorms can cause about 10% of storms in an unconducive environment to rapidly intensify, even though the other 90% do not, Judt said.

“There could be a mechanism we haven’t discovered yet that would enable us to identify the 10 from the 90,” he said. “My working hypothesis is that it’s random, but it’s important for forecasters to be aware that rapid intensification is a typical process even in an unfavorable environment.”

This material is based upon work supported by the National Center for Atmospheric Research, a major facility sponsored by the National Science Foundation and managed by the University Corporation for Atmospheric Research. Any opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

About the article

Title: “Marathon versus Sprint: Two Modes of Tropical Cyclone Rapid Intensification in a Global Convection-Permitting Simulation”

Authors: Falko Judt, Rosimar Rios-Berrios, and George H. Bryan

Journal: Monthly Weather Review

On the web: news.ucar.edu

On X: @NCAR_Science

END

Scientists find two ways that hurricanes rapidly intensify

New study may help forecasters better predict dangerous storms

2023-10-26

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Is red meat intake linked to inflammation?

2023-10-26

Inflammation is a risk factor for many chronic diseases, including cardiovascular disease (CVD), and the impact of diet on inflammation is an area of growing scientific interest. In particular, recommendations to limit red meat consumption are often based, in part, on old studies suggesting that red meat negatively affects inflammation – yet more recent studies have not supported this.

“The role of diet, including red meat, on inflammation and disease risk has not been adequately studied, which can lead to public health recommendations that are not based on strong evidence,” said Dr. Alexis Wood, associate professor of pediatrics – ...

RIT’s Campanelli receives award for work in gravitational wave science

2023-10-26

Rochester Institute of Technology distinguished professor and founding director of the Center for Computational Relativity and Gravitation Manuela Campanelli has been honored with the American Physical Society’s (APS) 2024 Richard A. Isaacson Award in Gravitational-Wave Science for her extraordinary contributions to and leadership in the understanding and simulation of merging binaries of compact objects in strong-field gravity.

The annual honor is granted to esteemed scientists for their remarkable achievements in the fields of gravitational-wave physics, gravitational wave astrophysics, and associated ...

Fruit, nectar, bugs and blood: How bat teeth and jaws evolved for a diverse dinnertime

2023-10-26

Link to full release with images:

https://www.washington.edu/news/2023/10/26/bat-teeth/

(Note: researcher contact information at the end)

They don’t know it, but Darwin’s finches changed the world. These closely related species — native to the Galapagos Islands — each sport a uniquely shaped beak that matches their preferred diet. Studying these birds helped Charles Darwin develop the theory of evolution by natural selection.

A group of bats has a similar — ...

Mobile stroke units increase odds of averting stroke

2023-10-26

Receiving a clot-busting drug in an ambulance-based mobile stroke unit (MSU) increases the likelihood of averting strokes and complete recovery compared with standard hospital emergency care, according to researchers at Weill Cornell Medicine, NewYork-Presbyterian, UTHealth Houston, Memorial Hermann-Texas Medical Center and five other medical centers across the United States.

The study, published online in the Annals of Neurology on Oct. 6, determined that MSU care was associated with both increased odds of averting stroke compared with hospital emergency medical service (EMS) – ...

Why are so many migrant families still separated? Chaos in the data

2023-10-26

U.S. government reached a settlement with thousands of families separated under the zero-tolerance policy

Experts highlight ‘mountain of a challenge’ that U.S. Family Reunification Task Force has had in accounting for separations

Task force reuniting families is working within a limited scope of separated families

‘If using DNA data to reunite families could help even one child, it’s worth giving it a shot,’ says researcher

CHICAGO --- Five years since the retraction of the Trump-era zero-tolerance policy on illegal border crossings, which resulted in the separation ...

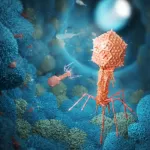

Mammalian cells may consume bacteria-killing viruses to promote cellular health

2023-10-26

Bacteriophages, also called phages, are viruses that infect and kill bacteria, their natural hosts. But from a macromolecular viewpoint, phages can be viewed as nutritionally enriched packets of nucleotides wrapped in an amino acid shell. A study published October 26th in the open access journal PLOS Biology by Jeremy J. Barr at Monash University, Victoria, Australia, and colleagues suggests that mammalian cells internalize phages as a resource to promote cellular growth and survival.

Phage interactions with bacteria are well known, and interactions between bacteria and their mammalian host can lead ...

New research finds stress and strain changes metal electronic structure

2023-10-26

New research from the University of Birmingham shows that the electronic structure of metals can strongly affect their mechanical properties.

The research, published today (26th October) in the journal Science, demonstrates experimentally, for the first time, that the electronic and mechanical properties of a metal are connected. It was previously understood theoretically that there would be a connection, but it was thought that it would be too small to detect in an experiment.

Dr Clifford Hicks, Reader in Condensed Matter Physics, who worked on the study said: “Mechanical properties are typically described ...

A superatomic semiconductor sets a speed record

2023-10-26

Semiconductors—most notably, silicon—underpin the computers, cellphones, and other electronic devices that power our daily lives, including the device on which you are reading this article. As ubiquitous as semiconductors have become, they come with limitations. The atomic structure of any material vibrates, which creates quantum particles called phonons. Phonons in turn cause the particles—either electrons or electron-hole pairs called excitons—that carry energy and information around electronic devices to scatter in a matter of nanometers and femtoseconds. This means that energy is lost in the form of heat, and that information transfer has ...

Uncovered in Uganda: Evidence for menopause in wild chimpanzees

2023-10-26

To date, research has suggested that only humans and some species of toothed whales live many years of active life after the loss of reproductive ability. But now, a new study shows female chimpanzees in Uganda show signs of menopause – surviving long past the end of their ability to reproduce. Signs of menopause in wild chimpanzees may provide insights into the evolution of this rare trait in humans. The vast majority of mammals stay fertile until the very ends of their lives, with humans and several species of toothed whales as the outliers; they experience menopause. In humans, menopause ...

A new “species” of legal subject: AI-led corporate entities, requiring interspecific legal frameworks

2023-10-26

For the first time in human history, say Daniel Gervais and John Nay in a Policy Forum, nonhuman entities that are not directed by humans – such as artificial intelligence (AI)-operated corporations – should enter the legal system as a new “species” of legal subject. AI has evolved to the point where it could function as a legal subject with rights and obligations, say the authors. As such, before the issue becomes too complex and difficult to disentangle, “interspecific” legal frameworks need to be developed by which AI can be treated as legal subjects, they write. Until now, the legal system has been univocal ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Tools to glimpse how “helicity” impacts matter and light

Smartphone app can help men last longer in bed

Longest recorded journey of a juvenile fisher to find new forest home

Indiana signs landmark education law to advance data science in schools

A new RNA therapy could help the heart repair itself

The dehumanization effect: New PSU research examines how abusive supervision impacts employee agency and burnout

New gel-based system allows bacteria to act as bioelectrical sensors

The power of photonics

From pioneer to leader: Alex Zhavoronkov chairs precision aging discussion and presents Luminary Award to OpenAI president at PMWC 2026

Bursting cancer-seeking microbubbles to deliver deadly drugs

In a South Carolina swamp, researchers uncover secrets of firefly synchrony

American Meteorological Society and partners issue statement on public availability of scientific evidence on climate change

How far will seniors go for a doctor visit? Often much farther than expected

Selfish sperm hijack genetic gatekeeper to kill healthy rivals

Excessive smartphone use associated with symptoms of eating disorder and body dissatisfaction in young people

‘Just-shoring’ puts justice at the center of critical minerals policy

A new method produces CAR-T cells to keep fighting disease longer

Scientists confirm existence of molecule long believed to occur in oxidation

The ghosts we see

ACC/AHA issue updated guideline for managing lipids, cholesterol

Targeting two flu proteins sharply reduces airborne spread

Heavy water expands energy potential of carbon nanotube yarns

AMS Science Preview: Mississippi River, ocean carbon storage, gender and floods

High-altitude survival gene may help reverse nerve damage

Spatially decoupling active-sites strategy proposed for efficient methanol synthesis from carbon dioxide

Recovery experiences of older adults and their caregivers after major elective noncardiac surgery

Geographic accessibility of deceased organ donor care units

How materials informatics aids photocatalyst design for hydrogen production

BSO recapitulates anti-obesity effects of sulfur amino acid restriction without bone loss

Chinese Neurosurgical Journal reports faster robot-assisted brain angiography

[Press-News.org] Scientists find two ways that hurricanes rapidly intensifyNew study may help forecasters better predict dangerous storms