(Press-News.org) Link to full release with images:

https://www.washington.edu/news/2023/10/26/bat-teeth/

(Note: researcher contact information at the end)

They don’t know it, but Darwin’s finches changed the world. These closely related species — native to the Galapagos Islands — each sport a uniquely shaped beak that matches their preferred diet. Studying these birds helped Charles Darwin develop the theory of evolution by natural selection.

A group of bats has a similar — and more expansive — evolutionary story to tell. There are more than 200 species of noctilionoid bats, mostly in the American tropics. And despite being close relatives, their jaws evolved in wildly divergent shapes and sizes to exploit different food sources. A paper published Aug. 22 in Nature Communications shows those adaptations include dramatic, but also consistent, modifications to tooth number, size, shape and position. For example, bats with short snouts lack certain teeth, presumably due to a lack of space. Species with longer jaws have room for more teeth — and, like humans, their total tooth complement is closer to what the ancestor of placental mammals had.

According to the research team behind this study, comparing noctilionoid species can reveal a lot about how mammalian faces evolved and developed, particularly jaws and teeth. And as a bonus, they can also answer some outstanding questions about how our own pearly whites form and grow.

“Bats have all four types of teeth — incisors, canines, premolars and molars — just like we do,” said co-author Sharlene Santana, a University of Washington professor of biology and curator of mammals at the Burke Museum of Natural History & Culture. “And noctilionoid bats evolved a huge diversity of diets in as little as 25 million years, which is a very short amount of time for these adaptations to occur.”

“There are noctilionoid species that have short faces like bulldogs with powerful jaws that can bite the tough exterior of the fruits that they eat. Other species have long snouts to help them drink nectar from flowers. How did this diversity evolve so quickly? What had to change in their jaws and teeth to make this possible?” said lead author Alexa Sadier, an incoming faculty member at the Institute of Evolutionary Science of Montpellier in France, who began this project as a postdoctoral researcher at the University California, Los Angeles.

Scientists don’t know what triggered this frenzy of dietary adaptation in noctilionoid bats. But today different noctilionoid species feast on insects, fruit, nectar, fish and even blood — since this group also includes the infamous vampire bats.

The team used CT scans and other methods to analyze the shapes and sizes of jaws, premolars and molars in more than 100 noctilionoid species. The bats included both museum specimens and a limited number of wild bats captured for study purposes. The researchers compared the relative sizes of teeth and other cranial features among species with different types of diets, and used mathematical modeling to determine how those differences are generated during development.

The team found that, in noctilionoid bats, certain “developmental rules” caused them to generate the right assortment of teeth to fit in their diet-formed grins. For example, bats with long jaws — like nectar-feeders — or intermediate jaws, like many insect-eaters, tended to have the usual complement of three premolars and three molars on each side of the jaw. But bats with short jaws, including most fruit-eating bats, tended to ditch the middle premolar or the back molar, if not both.

“When you have more space, you can have more teeth,” said Sadier. “But for bats with a shorter space, even though they have a more powerful bite, you simply run out of room for all these teeth.”

Having a shorter jaw may also explain why many short-faced bats also tended to have wider front molars.

“The first teeth to appear tend to grow bigger since there is not enough space for the next ones to emerge,” said Sadier.

“This project is giving us the opportunity to actually test some of the assumptions that have been made about how tooth growth, shape and size are regulated in mammals,” said Santana. “We know surprisingly little about how these very important structures develop!”

Many studies about mammalian tooth development were done in mice, which have only molars and heavily modified incisors. Scientists are not entirely sure if the genes and developmental patterns that control tooth development in mice also operate in mammals with more “ancestral” sets of chompers — like bats and humans.

Sadier, Santana and their colleagues believe their project, which is ongoing, can start to answer these questions in bats — along with many other outstanding questions about how evolution shapes mammalian features. They’re expanding this study to include noctilionoid incisors and canines, and hope to uncover more of the genetic and developmental mechanisms that control tooth development in this diverse group of bats.

“We see such strong selective pressures in these bats: Shapes have to closely match their function,” said Santana. “I think there are many more evolutionary secrets hidden in these species.”

Co-authors are Neal Anthwal, a research associate at King’s College London; Andrew Krause, an assistant professor at the Durham University in the U.K.; Renaud Dessalles, a mathematician with Green Shield Technology; Robert Haase, a researcher at the Dresden University of Technology in Germany; UCLA research scientists Michael Lake, Laurent Bentolila and Natalie Nieves; and Karen Sears, a professor at UCLA. The research is funded by the National Science Foundation.

###

For more information, contact Santana at ssantana@uw.edu and Sadier at alexa.sadier@gmail.com.

NSF grant numbers: 2017738, 201780

END

Receiving a clot-busting drug in an ambulance-based mobile stroke unit (MSU) increases the likelihood of averting strokes and complete recovery compared with standard hospital emergency care, according to researchers at Weill Cornell Medicine, NewYork-Presbyterian, UTHealth Houston, Memorial Hermann-Texas Medical Center and five other medical centers across the United States.

The study, published online in the Annals of Neurology on Oct. 6, determined that MSU care was associated with both increased odds of averting stroke compared with hospital emergency medical service (EMS) – ...

U.S. government reached a settlement with thousands of families separated under the zero-tolerance policy

Experts highlight ‘mountain of a challenge’ that U.S. Family Reunification Task Force has had in accounting for separations

Task force reuniting families is working within a limited scope of separated families

‘If using DNA data to reunite families could help even one child, it’s worth giving it a shot,’ says researcher

CHICAGO --- Five years since the retraction of the Trump-era zero-tolerance policy on illegal border crossings, which resulted in the separation ...

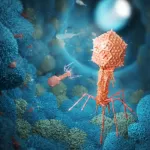

Bacteriophages, also called phages, are viruses that infect and kill bacteria, their natural hosts. But from a macromolecular viewpoint, phages can be viewed as nutritionally enriched packets of nucleotides wrapped in an amino acid shell. A study published October 26th in the open access journal PLOS Biology by Jeremy J. Barr at Monash University, Victoria, Australia, and colleagues suggests that mammalian cells internalize phages as a resource to promote cellular growth and survival.

Phage interactions with bacteria are well known, and interactions between bacteria and their mammalian host can lead ...

New research from the University of Birmingham shows that the electronic structure of metals can strongly affect their mechanical properties.

The research, published today (26th October) in the journal Science, demonstrates experimentally, for the first time, that the electronic and mechanical properties of a metal are connected. It was previously understood theoretically that there would be a connection, but it was thought that it would be too small to detect in an experiment.

Dr Clifford Hicks, Reader in Condensed Matter Physics, who worked on the study said: “Mechanical properties are typically described ...

Semiconductors—most notably, silicon—underpin the computers, cellphones, and other electronic devices that power our daily lives, including the device on which you are reading this article. As ubiquitous as semiconductors have become, they come with limitations. The atomic structure of any material vibrates, which creates quantum particles called phonons. Phonons in turn cause the particles—either electrons or electron-hole pairs called excitons—that carry energy and information around electronic devices to scatter in a matter of nanometers and femtoseconds. This means that energy is lost in the form of heat, and that information transfer has ...

To date, research has suggested that only humans and some species of toothed whales live many years of active life after the loss of reproductive ability. But now, a new study shows female chimpanzees in Uganda show signs of menopause – surviving long past the end of their ability to reproduce. Signs of menopause in wild chimpanzees may provide insights into the evolution of this rare trait in humans. The vast majority of mammals stay fertile until the very ends of their lives, with humans and several species of toothed whales as the outliers; they experience menopause. In humans, menopause ...

For the first time in human history, say Daniel Gervais and John Nay in a Policy Forum, nonhuman entities that are not directed by humans – such as artificial intelligence (AI)-operated corporations – should enter the legal system as a new “species” of legal subject. AI has evolved to the point where it could function as a legal subject with rights and obligations, say the authors. As such, before the issue becomes too complex and difficult to disentangle, “interspecific” legal frameworks need to be developed by which AI can be treated as legal subjects, they write. Until now, the legal system has been univocal ...

While small, the hypothalamus – a complex structure located deep in the brain – plays a gargantuan role in coordinating the wide array of neuronal signals that are responsible for keeping the body in a stable state. In a Special Issue of Science, authors across four Reviews unpack this key brain region’s impact on physiological and behavioral homeostasis.

The hypothalamus consists of a complex collection of neural circuits. These circuits receive, process, and integrate sensory inputs to drive coordinated communication via a range of behavioral, ...

In a Perspective, Stephen Tang and Samuel Sternberg discuss retroelement-based gene editing as a safer alternative to CRISPR-Cas approaches. Precision genome editing technologies have transformed modern biology. Capabilities for programable DNA targeting have improved rapidly, largely due to the development of bacterial RNA-guided CRISPR-Cas systems, which allow precise cleavage of target DNA sequences. However, CRISPR-Cas9 systems generate a DNA double strand break (DSB), which activates cellular DNA repair pathways that can lead to unwanted and complex byproducts, ...

Key takeaways

Female chimpanzees in Uganda’s Ngogo community experienced a menopausal transition similar to women.

Fertility among chimpanzees studied declined after age 30, and no births were observed after age 50.

The data can help researchers better understand why menopause and post-fertile survival occur in nature and how it evolved in the human species.

A team of researchers studying the Ngogo community of wild chimpanzees in western Uganda’s Kibale National Park for two decades has published a report in Science showing that females in this population can ...