(Press-News.org) Order wine at a fancy restaurant, and the sommelier might describe its aroma as having notes of citrus, tropical fruit, or flowers. Yet, when you take a whiff, it might just smell like … wine. How can wine connoisseurs pick out such similar scents?

Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) Associate Professor Saket Navlakha and Salk Institute researcher Shyam Srinivasan may have the answer. They have found that certain neurons allow fruit flies and mice to tell apart distinct smells. The team also observed that with experience, another group of neurons helps the animals distinguish between very similar odors.

The study was inspired by research from former CSHL Assistant Professor Glenn Turner. Years ago, Turner noticed something odd. When exposed to the same scent, some fruit fly neurons fired consistently while others varied from trial to trial. At the time, many researchers dismissed these differences as a product of background noise. But Navlakha and Srinivasan wondered whether the variations might serve a purpose.

“There were two things we were interested in,” Navlakha says. “Where is this variability coming from? And is it good for anything?”

To address these questions, the team created a fruit fly smell model. The model showed that the variability came from a deeper circuit of the brain than previously thought. This suggested the variation was indeed meaningful.

Next, the team observed that some neurons respond differently to two very dissimilar odors, but the same to similar smells. The researchers called these neurons reliable cells. This small group of cells helps flies quickly distinguish between differing odors. Another much larger group of neurons responds unpredictably when exposed to similar smells. These neurons, which the researchers call unreliable cells, might help us learn to identify specific scents in a glass of wine, for example.

“The model we developed shows these unreliable cells are useful,” Srinivasan says. “But it requires many learning bouts to take advantage of them.”

Of course, this research isn’t just for wine drinkers. Srinivasan says the results might help explain how we learn to differentiate between similarities detected by other senses, and how we make decisions based on those sensory inputs. The findings could also lead to better machine-learning models. Unlike fruit fly and mouse neurons, computers generally respond the same to the same inputs.

“Maybe you don’t want a machine-learning model to represent the same input the same way every time,” Navlakha explains. “In more continual learning systems, variability could be useful.”

That means this research could someday help make AI more discerning and reliable.

END

Smells like learning

2023-10-31

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

How sunflowers see the sun

2023-10-31

Sunflowers famously turn their faces to follow the sun as it crosses the sky. But how do sunflowers “see” the sun to follow it? New work from plant biologists at the University of California, Davis, published Oct. 31 in PLOS Biology, shows that they use a different, novel mechanism from that previously thought.

“This was a total surprise for us,” said Stacey Harmer, professor of plant biology at UC Davis and senior author on the paper.

Most plants show phototropism – the ability to grow toward a ...

Climate-smart cows could deliver 10-20x more milk in Global South

2023-10-31

URBANA, Ill. — A team of animal scientists from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign is set to deliver a potential game changer for subsistence farmers in Tanzania: cows that produce up to 20 times the milk of indigenous breeds.

The effort, published in Animal Frontiers, marries the milk-producing prowess of Holsteins and Jerseys with the heat, drought, and disease-resistance of Gyrs, an indigenous cattle breed common in tropical countries. Five generations of crosses result in cattle capable of ...

SARS-CoV-2 infection affects energy stores in the body, study shows

2023-10-31

CHAPEL HILL, N.C. – The lungs were once at the forefront of SARS-Cov-2 research, but as reports of organ failure and other serious complications poured in, scientists set out to discover how and why the respiratory virus was causing serious damage to the body's major organs, including the lungs.

An interdisciplinary COVID-19 International Research Team (COV-IRT), which includes UNC School of Medicine’s Jonathan C. Schisler, PhD, found that SARS-CoV-2 alters mitochondria on a genetic ...

Study examines financial sustainability of affordable housing-with-services models for older adults

2023-10-31

A groundbreaking study published in the journal Research in Aging sheds light on the financial challenges of housing-with-health-services models for low-income older adults. The report explores strategies for ensuring the sustainability of these beneficial efforts.

The study was conducted in partnership with Hebrew SeniorLife, a Harvard Medical School-affiliated nonprofit organization serving older adults in the Greater Boston area. It drew on insights from 31 key informational interviews and three focus groups ...

Earlier detection of cardiometabolic risk factors for kids may be possible through next generation biomarkers

2023-10-31

The next generation of cardiometabolic biomarkers should pave the way for earlier detection of risk factors for conditions such as obesity, diabetes and heart disease in children, according to a new scientific statement from the American Heart Association published in the journal Circulation.

“The rising number of children with major risk factors for cardiometabolic conditions represents a potential tsunami of preventable disease for our healthcare system,” says the statement’s lead author Michele Mietus-Snyder, M.D., ...

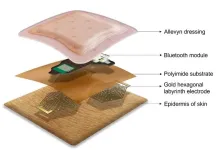

Wearable heart monitor ticks all the boxes for better healthcare: Study

2023-10-31

A new compact, lightweight, gel-free and waterproof electrocardiogram (ECG) sensor offers more comfort and less skin irritation, compared to similar heart monitoring devices on the market.

ECGs help manage cardiovascular disease – which affects around 4 million Australians and kills more than 100 people every day – by alerting users to seek medical care.

The team led by RMIT University in Australia has made the wearable ECG device that could be used to prevent heart attacks for people with cardiovascular disease, including in remote healthcare and ...

Binghamton researchers get FDA approval for drug to treat world’s most common genetic disease

2023-10-31

BINGHAMTON, N.Y. -- A new drug developed by professors from the School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences at Binghamton University has received Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for the treatment of patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), a common genetic disease that mostly affects young boys.

DMD is the most common genetic disease. It leads to the loss of the dystrophin protein in muscle tissues, with progressive weakness and challenges with day-to-day activities. The DMD gene is the largest gene in the human genome, ...

Trastuzumab deruxtecan: advantages also in HER2-low breast cancer

2023-10-31

The antibody-drug conjugate trastuzumab deruxtecan is approved for various therapeutic indications. Since March 2023, it can also be used as monotherapy for the treatment of adults with unresectable or metastatic HER2-low breast cancer who have received prior chemotherapy at this disease stage or developed disease recurrence early after adjuvant chemotherapy. Treatment with trastuzumab deruxtecan is the first approved therapy for patients with HER2-low breast cancer. The German Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG) examined in an early benefit assessment whether the antibody-drug ...

Children with ADHD frequently use healthcare service before diagnosis, study finds

2023-10-31

Children and young people with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) use healthcare services twice as often in the two years before their diagnosis, a study by researchers at the University of Nottingham and King’s College London has found.

The research, published today in the journal Archives of Disease in Childhood shows that children with the neurodevelopmental disorder are twice as likely to see their GP, go to hospital for an admission, and even have operations, compared to children without ADHD.

The researchers say the results support the need for healthcare professionals to consider a potential diagnosis of ADHD in children who ...

The first oncogene was found more than 40 years ago. CNIO researchers have just discovered that it has a previously unknown mechanism of action

2023-10-31

In the late 1970s, the relationship between the c-Src gene and cancer was discovered. The first oncogene was identified.

Since then, c-Src has been found to be overactivated in half of colon, liver, lung, breast, prostate and pancreatic tumors, but its function is not yet fully understood.

CNIO researchers have now discovered that this oncogene is capable of 'self-activation', by means of a previously undescribed molecular mechanism. This finding has implications for the development of new drugs.

In ...