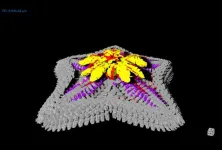

But now, labs at Stanford University and UC Berkeley, each led by Chan Zuckerberg Biohub San Francisco Investigators, have published a study finding that the truth is closer to the absolute reverse. In short, while the team detected gene signatures associated with head development just about everywhere in juvenile sea stars, expression of genes that code for an animal’s torso and tail sections were largely missing.

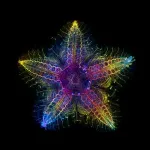

In another surprising finding, molecular signatures typically associated with the front-most portion of the head were localized to the middle of each of the sea star’s arms, with these signatures becoming progressively more posterior moving out towards the arms’ edges.

The research, published Nov. 1 in Nature, suggests that, far from being headless, over evolutionary time sea stars lost their bodies to become only heads.

“It’s as if the sea star is completely missing a trunk, and is best described as just a head crawling along the seafloor,” said Laurent Formery, a Biohub-funded postdoctoral scholar and lead author of the new study. “It’s not at all what scientists have assumed about these animals.”

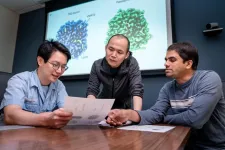

Two of the study’s three co–senior authors, marine and developmental biologist Christopher Lowe of Stanford University and UC Berkeley’s Daniel Rokhsar, an expert on the molecular evolution of animal species, have been collaborating for a decade, and were members of a team funded by CZ Biohub SF’s Intercampus Research Awards. Lowe cited the award, which has supported a joint postdoctoral scholar position between both labs for Formery, as an important catalyst in the new discovery.

“The work we proposed to do together was very ambitious and the kind of thing that generally does not play very well with traditional funding mechanisms,” Lowe said. “The Biohub’s willingness to take risks and provide support for a joint position between our labs has been critical for the success of this project.”

A star-shaped puzzle

Almost all animals, including humans, are bilaterally symmetrical, meaning they can be split into two mirrored halves along a single axis extending from their head to their tail. In 1995 the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded to three scientists who had used fruit flies to demonstrate that the bilateral, head-to-tail body plan seen in most animals arises from the action of a series of molecular switches, coded by genes, expressed in defined head and trunk regions.

Researchers have since confirmed that this same genetic programming is shared by the vast majority of animal species, including vertebrates like humans and fish, and in many invertebrates such as insects and worms.

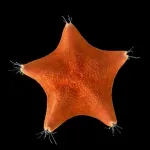

But the body plan of sea stars has long confounded scientists’ understanding of animal evolution. Instead of displaying bilateral symmetry, adult sea stars — and related echinoderms such as sea urchins and sea cucumbers — have a five-fold axis of symmetry without a clear head or tail. And no one has been able to determine how genetic programming drives this unusual five-fold symmetry.

Some scientists have proposed that in sea stars, the head-to-tail axis might extend from the animal’s armored back to its underbelly, which is carpeted in so-called tube feet. Others have suggested each of the sea star’s five arms corresponds to a copy of a conventional head-to-tail axis.

Efforts to definitively confirm such hypotheses have faced challenges, however, largely because methods for detecting gene expression, developed primarily in a small number of model organisms like mice and flies, don’t work well in the tissue of young sea stars. For years, Lowe and his colleagues had itched to bring genetic information to bear on the question by mapping genetic activity across developing sea stars. But without the complex genetic tool kits developed over decades of research that exist for typical model organisms, such a comprehensive analysis was daunting.

Game-changing technology

Lowe encountered a solution for this problem at one of the regular San Francisco meetings of Biohub Investigators, where another researcher suggested he contact PacBio, a Silicon Valley–based company that builds genome-sequencing devices. Over the previous five years, PacBio had been perfecting a technique for sequencing massive quantities of genetic material using postage stamp–sized chips jam-packed with millions of individual chemical reactors, each primed to simultaneously read long stretches of DNA captured within.

Unlike traditional sequencing, which requires chopping genetic material into small pieces to ensure accuracy, PacBio’s approach, called HiFi sequencing, can pull highly accurate data from intact, gene-sized DNA strands, making the process much faster and cheaper. It was exactly what Lowe and his team needed to establish a process for studying sea star genetics from the ground up.

“The kind of sequencing that would have taken months can now be done in a matter of hours, and it’s hundreds of times cheaper than just five years ago,” said David Rank, also a co–senior author of the new study and a former PacBio Scientific Fellow. “These advances meant we could start essentially from scratch in an organism that’s not typically studied in the lab and put together the kind of detailed study that would have been impossible 10 years ago.”

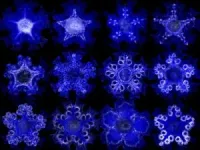

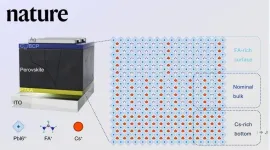

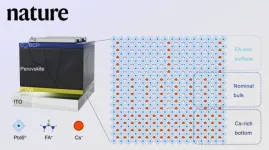

This technology allowed the researchers to sequence the genomes of the sea stars and employ an approach called spatial transcriptomics, through which they could pinpoint which sea star genes are active at precise locations in the organism. To search for patterns that would indicate a head-to-tail axis, the researchers examined gene expression differences in three different directions across the body: from the sea star’s center to its arm tips, from its top to its underbelly, and from one side edge of its arms to the other. Then, to get a closer look at how certain key genes were behaving, they labeled them one by one with fluorescent dyes to create a detailed map of their distribution in the sea star body.

The researchers found that neither of the prominent hypotheses of sea star body plan structure was correct. Instead, they saw that gene expression corresponding to the forebrain in humans and other bilaterally symmetrical animals was located along the midline of sea stars’ arms, with genetic expression corresponding to that of the human midbrain towards the arms’ outer edges. While the genes marking different subregions of the head in humans and other bilaterians were expressed in the sea star, only one of the genes typically associated with the trunk in animals was expressed, at the very edges of the sea stars’ arms.

“These results suggest that the echinoderms, and sea stars in particular, have the most dramatic example of decoupling of the head and the trunk regions that we are aware of today,” said Formery, adding that some bizarre-looking sea star ancestors preserved in the fossil record do appear to have had a trunk. “It just opens a ton of new questions that we can now start to explore.”

A door to new discoveries

Questions that the team hopes to address next involve whether the genetic patterning seen in sea stars also shows up in sea urchins and sea cucumbers. For his part, Formery also wants to look into what the sea star can teach us about the evolution of the nervous system, which, he said, no one quite understands in echinoderms.

Learning more about the sea star and its relatives will not only help solve key mysteries of animal evolution, but could also inspire innovations in medicine, the researchers said. Sea stars walk by moving water through thousands of tube feet and digest their prey by extruding their stomachs outside of their bodies. It only stands to reason that these unusual creatures have also evolved completely unexpected strategies for staying healthy — which, if we took the time to understand them, could expand our approaches to combating human disease.

“It’s certainly harder to work in organisms that are less frequently studied,” Rokhsar said. “But if we take the opportunity to explore unusual animals that are operating in unusual ways, that means we are broadening our perspective of biology, which is eventually going to help us solve both ecological and biomedical problems.”

# # #

About the Chan Zuckerberg Biohub San Francisco

CZ Biohub San Francisco, part of the Chan Zuckerberg Biohub Network, is a nonprofit biomedical research center founded in 2016. CZ Biohub SF’s researchers, engineers, and data scientists, in collaboration with colleagues at our partner universities — Stanford University; the University of California, Berkeley; and the University of California, San Francisco — seek to understand the fundamental mechanisms underlying disease and develop new technologies that will lead to actionable diagnostics and effective therapies. Learn more at czbiohub.org/sf.

END