(Press-News.org)

Tokyo, Japan – Researchers from Tokyo Metropolitan University have identified key factors in the mechanism behind DNA repair in our bodies. For the first time, they showed that the “proofreading” portion of the DNA replicating enzyme polymerase epsilon ensured safe termination of replication at damaged portions of the DNA strand, ultimately saving DNA from severe damage. This new knowledge arms scientists with ways to make anti-cancer drugs more effective, and new diagnostic methods.

Our DNA is under attack. Every day, around 55,000 single-strand breaks (SSBs) appear in the strands making up DNA helices in individual cells. When polymerases, molecules that replicate DNA strands, try to make new helices from strands with breaks in them, they can break the helix, creating what’s known as a single-ended double-stranded break (seDSB). Thankfully, cells have their own ways of dealing with strand damage. One is homology directed repair (HDR), where double stranded breaks are fixed. Another is “fork reversal”, where the replication process is reversed, preventing the single-strand nicks turning into DSBs in the first place.

The exact mechanism behind fork reversal remains unknown. Understanding how DNA damage is prevented is paramount not only to prevent cancers, but also ensure the effectiveness of cancer drugs which rely on DNA damage. Take camptothecin (CPT), an anti-cancer drug that introduces lots of single-strand breaks; since cancer cells tend to replicate quicker, they create lots of seDSBs and die out, leaving normal cells less harmed.

Now, an international team led by Professor Kouji Hirata of Tokyo Metropolitan University have shed new light on how fork reversal works. They focused on polymerase epsilon, an enzyme responsible for making new DNA from a portion of the DNA which has unzipped. They discovered that the exonuclease, the “proofreading” portion of the polymerase that ensures copy accuracy, played a key role, a new, rare insight into the largely unknown molecular mechanism behind fork reversal.

Firstly, they found that cells which are deficient in the exonuclease part showed strong susceptibility to exposure to CPT. Suppression of a factor known as PARP, the only other player known to affect fork reversal, also led to increased cell death. However, when both were suppressed, there was no further increase in cell death beyond what was seen with PARP. This suggests that PARP and the polymerase epsilon exonuclease work together to trigger fork reversal. Furthermore, the team studied cells with the gene coding for BRCA1 (the breast cancer susceptibility protein) disrupted; additional deficiency of the exonuclease caused drastically increased sensitivity to CPT, far more than expected from either defect. Since BRCA1 deficiency is linked to a high risk of breast cancer, the exonuclease might be targeted to make drug treatments more effective.

The significance of this work is manyfold. They have shown that drugs targeting the polymerase epsilon exonuclease can amplify the effect of anti-cancer drugs. Equally importantly, defects to the exonuclease have also already been seen in a wide range of cancers, including intestinal cancer; this makes it likely that such cells have impaired fork reversal capability, a promising target for future diagnostics as well as treatments.

This work was supported by the Kanae Foundation, Shenzhen University, the Pearl River Talent Plan to introduce high-level talents [2021JC02Y089], the Takeda Science Foundation, a Tokyo Metropolitan Government Advanced Research Grant [R3-2], the Network-type Joint Usage/Research Center for Radiation Disaster Medical Science of Hiroshima University, Nagasaki University, Fukushima Medical University, the Yamada Science Foundation; JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers 16H06306, 16H12595, 20K06760, 22K15040, JP19KK0210, JP20H04337, JP21K19235, the National Natural Science Foundation of China [32250710138], the Uehara Memorial Foundation, Advanced Research Networks, the national key research and development program [2022YFA1302800], and the JSPS Core-to-Core Program. Funding to make the work open-access was provided through Tokyo Metropolitan Government Advanced Research Grant Number [R3-2].

END

MSU has a satellite uplink/LTN TV studio and Comrex line for radio interviews upon request.

There is a general understanding that pets have a positive impact on one’s well-being. A new study by Michigan State University found that although pet owners reported pets improving their lives, there was not a reliable association between pet ownership and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The study, published in the Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, assessed 767 people over three times in May 2020. The researchers took a mixed-method ...

MSU has a satellite uplink/LTN TV studio and Comrex line for radio interviews upon request.

A new study, conducted in collaboration between researchers at Michigan State University and Central Michigan University, found that public spending on social safety net programs and on education spending each independently impact high school graduation rates, which are a key predictor of health and well-being later in life.

The study, published in the Journal of Adolescent Health, tested whether public financing for education and social safety net programs that aim to help ...

MSU has a satellite uplink/LTN TV studio and Comrex line for radio interviews upon request.

Video and Images

Michigan State University researchers have solved the mystery of a poorly understood sperm structure called the cytoplasmic droplet, or CD. The CD is an expanded cytoplasm — watery, gel-like cell contents enclosed by cell membrane — found close to the head, at the neck of the sperm, in all mammals, including humans. This new genetic model is the first of its kind.

Despite ...

With Amazon aiming to make 10,000 deliveries with drones in Europe this year and Walmart planning to expand its drone delivery services to an additional 60,000 homes this year in the states, companies are investing more research and development funding into drone delivery, But are consumers ready to accept this change as the new normal?

Northwestern University’s Mobility and Behavior Lab, led by Amanda Stathopoulos, an associate professor of civil and environmental engineering, wanted to know if consumers were ready for robots to replace delivery drivers, in the form ...

Minneapolis, Minn. – In a recently released study, researchers at Hennepin Healthcare and other Minnesota health systems describe how a COVID-19 collaboration across Minnesota health systems was adapted to monitor near-real-time trends in substance use–related hospital and emergency department (ED) visits.

The Minnesota Electronic Health Record Consortium (MNEHRC), developed in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, repurposed its surveillance methods to identify health disparities and inform equity-driven approaches to the overdose epidemic.

MNEHRC’s study, "Minnesota Data Sharing May Be Model for Near-Real-Time Tracking of Drug Overdose Hospital ...

Rochester Institute of Technology’s Lucia Carichino, assistant professor in the School of Mathematics and Statistics, has received a Launching Early-Career Academic Pathways in the Mathematical and Physical Sciences (LEAPS-MPS) award from the National Science Foundation (NSF).

The award funds Carichino’s research in computational modeling of the interaction between the eye and a contact lens. Specifically, Carichino is focusing on orthokeratology (ortho-k) lenses that help reduce myopic progression in kids and young adults. She aims to develop a mathematical model that will ...

LA JOLLA, CA—Scientists at La Jolla Institute for Immunology (LJI) are investigating a talented type of T cell.

Most T cells only work in the person who made them. Your T cells fight threats by responding to molecular fragments that belong to a pathogen—but only when these molecules are bound with markers that come from your own tissues. Your influenza-fighting T cells can't help your neighbor, and vice versa.

"However, we all have T cells that do not obey these rules," says LJI Professor and President Emeritus Mitchell Kronenberg, Ph.D. "One of these cell types is mucosal-associated invariant ...

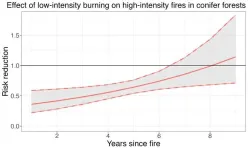

There is no longer any question of how to prevent high-intensity, often catastrophic, wildfires that have become increasingly frequent across the Western U.S., according to a new study by researchers at Stanford and Columbia universities. The analysis, published Nov. 10 in Science Advances, reveals that low-intensity burning, such as controlled or prescribed fires, managed wildfires, and tribal cultural burning, can dramatically reduce the risk of devastating fires for years at a time. The findings – some of the first to rigorously quantify the value of low-intensity fire – come while Congress is reassessing the U.S. Forest Service’s ...

Deep within every piece of magnetic material, electrons dance to the invisible tune of quantum mechanics. Their spins, akin to tiny atomic tops, dictate the magnetic behavior of the material they inhabit. This microscopic ballet is the cornerstone of magnetic phenomena, and it's these spins that a team of JILA researchers—headed by JILA Fellows and University of Colorado Boulder professors Margaret Murnane and Henry Kapteyn—has learned to control with remarkable precision, potentially redefining the future of electronics and data storage.

In a new Science Advances ...

MINNEAPOLIS/ST. PAUL (11/10/2023) — Researchers from the University of Minnesota Medical School examining the cause of cardiomyopathy discovered one out of every six patients with coronary artery disease had non-ischemic or dual cardiomyopathy.

The findings of this study were published this week in the peer-reviewed journal Circulation, the flagship journal of the American Heart Association.

Cardiomyopathies are diseases of the heart muscle. Patients with coronary artery disease can have cardiomyopathy from heart muscle ...