(Press-News.org) A hunger hormone produced in the gut can directly impact a decision-making part of the brain in order to drive an animal’s behaviour, finds a new study by UCL (University College London) researchers.

The study in mice, published in Neuron, is the first to show how hunger hormones can directly impact activity of the brain’s hippocampus when an animal is considering food.

Lead author Dr Andrew MacAskill (UCL Neuroscience, Physiology & Pharmacology) said: “We all know our decisions can be deeply influenced by our hunger, as food has a different meaning depending on whether we are hungry or full. Just think of how much you might buy when grocery shopping on an empty stomach. But what may seem like a simple concept is actually very complicated in reality; it requires the ability to use what's called ‘contextual learning’.

“We found that a part of the brain that is crucial for decision-making is surprisingly sensitive to the levels of hunger hormones produced in our gut, which we believe is helping our brains to contextualise our eating choices.”

For the study, the researchers put mice in an arena that had some food, and looked at how the mice acted when they were hungry or full, while imaging their brains in real time to investigate neural activity. All of the mice spent time investigating the food, but only the hungry animals would then begin eating.

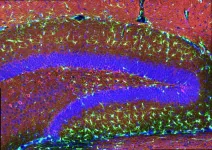

The researchers were focusing on brain activity in the ventral hippocampus (the underside of the hippocampus), a decision-making part of the brain which is understood to help us form and use memories to guide our behaviour.

The scientists found that activity in a subset of brain cells in the ventral hippocampus increased when animals approached food, and this activity inhibited the animal from eating.

But if the mouse was hungry, there was less neural activity in this area, so the hippocampus no longer stopped the animal from eating. The researchers found this corresponded to high levels of the hunger hormone ghrelin circulating in the blood.

Adding further clarity, the UCL researchers were able to experimentally make mice behave as if they were full, by activating these ventral hippocampal neurons, leading animals to stop eating even if they were hungry. The scientists achieved this result again by removing the receptors for the hunger hormone ghrelin from these neurons.

Prior studies have shown that the hippocampus of animals, including non-human primates, has receptors for ghrelin, but there was scant evidence for how these receptors work.

This finding has demonstrated how ghrelin receptors in the brain are put to use, showing the hunger hormone can cross the blood-brain barrier (which strictly restricts many substances in the blood from reaching the brain) and directly impact the brain to drive activity, controlling a circuit in the brain that is likely to be the same or similar in humans.

Dr MacAskill added: “It appears that the hippocampus puts the brakes on an animal’s instinct to eat when it encounters food, to ensure that the animal does not overeat – but if the animal is indeed hungry, hormones will direct the brain to switch off the brakes, so the animal goes ahead and begins eating.”

The scientists are continuing their research by investigating whether hunger can impact learning or memory, by seeing if mice perform non-food-specific tasks differently depending on how hungry they are. They say additional research might also shed light on whether there are similar mechanisms at play for stress or thirst.

The researchers hope their findings could contribute to research into the mechanisms of eating disorders, to see if ghrelin receptors in the hippocampus might be implicated, as well as with other links between diet and other health outcomes such as risk of mental illnesses.

First author Dr Ryan Wee (UCL Neuroscience, Physiology & Pharmacology) said: “Being able to make decisions based on how hungry we are is very important. If this goes wrong it can lead to serious health problems. We hope that by improving our understanding of how this works in the brain, we might be able to aid in the prevention and treatment of eating disorders.”

A hunger hormone produced in the gut can directly impact a decision-making part of the brain in order to drive an animal’s behaviour, finds a new study by UCL researchers.

The study in mice, published in Neuron, is the first to show how hunger hormones can directly impact activity of the brain’s hippocampus when an animal is considering food.

Lead author Dr Andrew MacAskill (UCL Neuroscience, Physiology & Pharmacology) said: “We all know our decisions can be deeply influenced by our hunger, as food has a different meaning depending on whether we are hungry or full. Just think of how much you might buy when grocery shopping on an empty stomach. But what may seem like a simple concept is actually very complicated in reality; it requires the ability to use what's called ‘contextual learning’.

“We found that a part of the brain that is crucial for decision-making is surprisingly sensitive to the levels of hunger hormones produced in our gut, which we believe is helping our brains to contextualise our eating choices.”

For the study, the researchers put mice in an arena that had some food, and looked at how the mice acted when they were hungry or full, while imaging their brains in real time to investigate neural activity. All of the mice spent time investigating the food, but only the hungry animals would then begin eating.

The researchers were focusing on brain activity in the ventral hippocampus (the underside of the hippocampus), a decision-making part of the brain which is understood to help us form and use memories to guide our behaviour.

The scientists found that activity in a subset of brain cells in the ventral hippocampus increased when animals approached food, and this activity inhibited the animal from eating.

But if the mouse was hungry, there was less neural activity in this area, so the hippocampus no longer stopped the animal from eating. The researchers found this corresponded to high levels of the hunger hormone ghrelin circulating in the blood.

Adding further clarity, the UCL researchers were able to experimentally make mice behave as if they were full, by activating these ventral hippocampal neurons, leading animals to stop eating even if they were hungry. The scientists achieved this result again by removing the receptors for the hunger hormone ghrelin from these neurons.

Prior studies have shown that the hippocampus of animals, including non-human primates, has receptors for ghrelin, but there was scant evidence for how these receptors work.

This finding has demonstrated how ghrelin receptors in the brain are put to use, showing the hunger hormone can cross the blood-brain barrier (which strictly restricts many substances in the blood from reaching the brain) and directly impact the brain to drive activity, controlling a circuit in the brain that is likely to be the same or similar in humans.

Dr MacAskill added: “It appears that the hippocampus puts the brakes on an animal’s instinct to eat when it encounters food, to ensure that the animal does not overeat – but if the animal is indeed hungry, hormones will direct the brain to switch off the brakes, so the animal goes ahead and begins eating.”

The scientists are continuing their research by investigating whether hunger can impact learning or memory, by seeing if mice perform non-food-specific tasks differently depending on how hungry they are. They say additional research might also shed light on whether there are similar mechanisms at play for stress or thirst.

The researchers hope their findings could contribute to research into the mechanisms of eating disorders, to see if ghrelin receptors in the hippocampus might be implicated, as well as with other links between diet and other health outcomes such as risk of mental illnesses.

First author Dr Ryan Wee (UCL Neuroscience, Physiology & Pharmacology) said: “Being able to make decisions based on how hungry we are is very important. If this goes wrong it can lead to serious health problems. We hope that by improving our understanding of how this works in the brain, we might be able to aid in the prevention and treatment of eating disorders.”

END

Hunger hormones impact decision-making brain area to drive behavior

2023-11-16

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Epidemic-economic model provides answers to key pandemic policy questions

2023-11-16

University of Oxford news release

Institute of New Economic Thinking

Embargoed until Thursday, 16 November 2023, 16:00 GMT

Is lockdown an effective response to a pandemic, or would it be better to let individuals spontaneously reduce their risk of infection? Research published today suggests these two highly-debated options lead to similar outcomes.

A ground-breaking economic-pandemic model, created by an international team of researchers, addresses some of the key policy debates of the Covid-19 pandemic but it ...

New research advances understanding of cancer risk in gene therapies

2023-11-16

Medical research has shown promising results regarding the potential of gene therapy to cure genetic conditions such as sickle cell disease and the findings of this study, published in Nature Medicine, offer important new insights into processes happening in the body after treatment.

The present study looked at samples from six patients with sickle cell disease who were undergoing gene therapy as part of a major clinical trial at Boston Children’s Hospital. The research brought together an international team of experts, to take a closer look at the genetic changes in the stem cells of patients before and after gene therapy ...

A small molecule blocks aversive memory formation, providing a potential treatment target for depression

2023-11-16

Depression is one of the most common mental illnesses in the world, but current anti-depressants have yet to meet the needs of many patients. Neuroscientists from City University of Hong Kong (CityU) recently discovered a small molecule that can effectively alleviate stress-induced depressive symptoms in mice by preventing aversive memory formation with a lower dosage, offering a new direction for developing anti-depressants in the future.

“Depression affects millions of individuals worldwide, necessitating more effective treatments. Conventional methods, such as drug therapy with delayed onset of action and psychotherapy, have limitations in yielding satisfactory ...

Plants that survived dinosaur extinction pulled nitrogen from air

2023-11-16

DURHAM, N.C. -- Once a favored food of grazing dinosaurs, an ancient lineage of plants called cycads helped sustain these and other prehistoric animals during the Mesozoic Era, starting 252 million years ago, by being plentiful in the forest understory. Today, just a few species of the palm-like plants survive in tropical and subtropical habitats.

Like their lumbering grazers, most cycads have gone extinct. Their disappearance from their prior habitats began during the late Mesozoic and continued into the early Cenozoic Era, punctuated by the cataclysmic asteroid impact and volcanic activity that mark the K-Pg boundary 66 million years ago. However, unlike the dinosaurs, somehow a few groups ...

The mind’s eye of a neural network system

2023-11-16

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. – In the background of image recognition software that can ID our friends on social media and wildflowers in our yard are neural networks, a type of artificial intelligence inspired by how own our brains process data. While neural networks sprint through data, their architecture makes it difficult to trace the origin of errors that are obvious to humans — like confusing a Converse high-top with an ankle boot — limiting their use in more vital work like health care image analysis or research. A new tool developed at Purdue University makes finding those errors as simple as spotting mountaintops from an airplane.

“In a sense, if a neural ...

Study finds motorist disorientation syndrome is not only caused by vestibular dysfunction

2023-11-16

Amsterdam, November 16, 2023 – A large case series aimed at understanding the factors underlying Motorist Disorientation Syndrome (MDS) has found that patients experience severe, consistent symptoms comparable to vestibular migraine. Previously there has been speculation that underlying peripheral vestibular hypofunction, when the inner ear part of the balance system is not working properly, contributes to this presentation. However, vestibular deficits were not a consistent feature in the patients studied. The findings have been published in the Journal of Vestibular Research.

In ...

Rabies virus variants from marmosets are found in bats

2023-11-16

Rabies virus variants closely related to variants present in White-tufted marmosets (Callithrix jacchus) have been detected in bats in Ceará state, Northeast Brazil.

Rabies is a deadly disease for humans. Its emergence in distinct wildlife species is a potential source of human infection and hence a public health concern. Marmosets are common in forests and conservation units throughout Brazil. In or near urban areas, they are often captured as pets and later abandoned. They have been linked ...

How a mutation in microglia elevates Alzheimer’s risk

2023-11-16

A rare but potent genetic mutation that alters a protein in the brain’s immune cells, known as microglia, can give people as much as a three-fold greater risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease. A new study by researchers in The Picower Institute for Learning and Memory at MIT details how the mutation undermines microglia function, explaining how it seems to generate that higher risk.

“This TREM2 R47H/+ mutation is a pretty important risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease,” said study lead author Jay Penney, a former postdoc in the MIT lab of Picower Professor Li-Huei ...

International team uses Insilico Medicine’s AI platform to find dual targets for aging and cancer

2023-11-16

An international research team is the first to use artificial intelligence (AI) analysis to identify dual-purpose target candidates for the treatment of cancer and aging, the most promising of which was experimentally validated. The findings were published in the journal Aging Cell.

Researchers from the University of Oslo, University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine, and clinical stage AI-driven drug discovery company Insilico Medicine used Insilico’s AI target discovery engine, PandaOmics, to analyze transcriptomic data derived from ...

New therapeutic strategy to reduce neuronal death in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

2023-11-16

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a neurodegenerative disease that affects neurons in the brain and spinal cord causing loss of muscle control. A study by the University of Barcelona has designed a potential therapeutic strategy to tackle this pathology that has no treatment to date. It is a molecular trap that prevents one of the most common genetic ALS-causing peptide compounds, the Poly-GR dipeptide, from causing its toxic effects in the body. The results show that this strategy reduces the death of neurons in patients and in an animal model (vinegar flies) of the disease.

The first authors of this international research study published in the journal Science Advances are ...